Can European agriculture be economically viable and environmentally friendly?

The relationship between agriculture and the environment is a hot topic in Europe right now. In recent months farmers across the continent have been protesting to highlight a system they see as increasingly unprofitable and burdened by EU rules aimed at making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050. Farmers have organised motorway and city blockades in tractors across Greece, Germany, Portugal, Poland and France, and last week pelted the European Parliament in Brussels with eggs.

In many ways, the farmers are feeling a perfect storm of economic repercussions of the Ukraine war and COVID pandemic, coupled with the ambitious new climate directives passed down by the EU. Costs of energy, fertiliser and transport have risen across the continent following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago. However, governments across Europe have sought to manage the effects of spiralling interest rates and the cost of living crisis by stemming rising food prices.

Whilst costs are up and profits are increasingly squeezed, European farmers are also feeling the pressure of a changing climate. 2023 was the year that the extremes of the climate emergency were starkly evident across the continent, as record-breaking droughts, wildfires and irrigation restrictions became commonplace across Southern Europe.

Amidst the challenges of producing food in a changing climate, farmers have to work within the rules set by the EU, which attempt to shift our agricultural system towards a more biodiversity-friendly and climate-neutral state. The European farming sector accounts for around 11% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, and as such will require significant reorganisation to achieve the European Green Deal goal of making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050.

Crucially, whilst the negative effects of intensive agriculture on European biodiversity are well documented, farmers argue that the targets in the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy and Nature Restoration Law to reduce their environmental impacts are overly punitive in the current economic climate. These targets include cutting fertiliser use by 20% and halving pesticide use by 2030, alongside allocating more land to non-agricultural use and doubling organic production.

In the wake of this wave of farmers’ protests the European Commission this week announced it was cancelling plans to half pesticide use in the EU by 2030. And last week, the bloc also announced delays to regulations on set-aside land intended to boost soil health and biodiversity in farmland across the continent.

This leaves European environmentalists in a tricky situation. Clearly, European farmers are increasingly squeezed economically. However, it is increasingly agreed that there is an urgent need for transformative actions to help preserve and restore European ecosystems. A key element of this work is to make agriculture more sustainable, both economically and environmentally.

As such, there is a pressing need to understand how different forms of agricultural practices affect European ecosystems, and whether the most harmful approaches can be transformed in ways that can support both nature and farmers’ livelihoods.

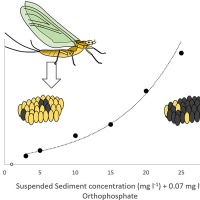

A new study explores how the impacts of different agricultural approaches across Europe affect the ecological health of rivers and streams across the continent. A research team led by Dr. Christian Schürings from UDE in Germany analysed data on agricultural land use across 27 European countries. Writing in Water Research, the researchers then linked this analysis to data on the ecological status of flowing waters across the continent, from small streams to huge rivers like the Ruhr and Rhine.

They found that the health of river and stream ecosystems in Europe is strongly influenced by the type of agriculture that is practiced in the landscapes which they flow through.

“Intensive farming has the greatest impact,” says Dr. Schürings. “This includes irrigated agriculture, as practiced in Southern Europe, for example in Spain, Portugal and Italy, and the intensive use of pesticides and fertilisers on land in Western Europe. This is particularly common in France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and the U.K.”

In many ways, this is not a surprising result. Aquatic scientists have long highlighted the negative impacts of intensive agriculture on our freshwaters, particularly due to pesticide and fertilisers polluting waterways, floodplains being lost to farmland, rivers straightened and abstracted for irrigation. The new study offers is a valuable map of where such agricultural pressure on freshwaters are highest across Europe – particularly clustered in Southern and Western Europe.

On the other hand, the study shows that less-intensive and organic forms of farming have little-to-no negative impacts on the rivers and streams which they border. Small-scale agriculture, which involves less chemical inputs and often occurs over a mosaic of habitats including hedgerows and fallow land, is shown by the authors to be a more river-friendly alternative to existing intensive practices.

“Our results underline that the transition to more sustainable forms of agriculture, such as organic farming, is beneficial for rivers,” says Dr. Schürings. However, the key question remains, how can this transition remain economically viable for farmers?

Decades of agricultural management under the Common Agricultural Policy have encouraged farmers to pursue economies of scale, where profits are boosted by bigger and more efficient farm holdings. Amidst the turmoil of farmers’ protests, how can the need to protect and restore freshwater life be upheld in decisions over how to manage European agriculture?

For co-author Dr. Sebastian Birk, the answer lies in the benefits that healthy, functioning ecosystems can provide to humans. As explored in the MERLIN project, such nature-based solutions can offer a system in which farmers can be economically rewarded for shifting their practices to benefit the environment.

In river catchments, this can include the restoration of floodplains to naturally-buffer flood waters, or the creation of wildflower meadows to boost pollinating insect populations. Such approaches could offer farmers incentives to reduce their environmental impacts, whilst benefiting economically from the healthy functioning of the ecosystems on which they rely.

For Dr. Birk, this means that, “water protection and agriculture can go hand in hand. The EU should support this through a restructuring of agricultural subsidies, so that the environmental services provided by agriculture are more strongly rewarded.”

///

Comments are closed.