Daylighting Urban Rivers

Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, South Korea, daylighted from sewers in 2003. Image: Kaizer Rangwala, Flickr.

Many towns and cities around the world have unseen flows of water which snake underneath concrete streets: ‘lost’ rivers which have been rerouted into sewers, drains and culverts as urban areas have grown. See, for example, how the London’s Lost Rivers project has documented dozens of tributaries of the Thames which now flow largely underground as a subterranean tangle of unseen streams.

River restoration – the restoration of water flows and aquatic life to a largely ‘natural’ state – has been a topic of increasing interest over recent years, and organisations like the River Restoration Centre and the European Centre for River Restoration have formed to promote restoration work.

Deculverting or ‘daylighting’ is the process of uncovering buried urban rivers and streams, and restoring them to more natural conditions. Daylighting can create new habitat for plants and animals, potentially reduce flood risks, and create new ‘green corridors’ through urban areas, a good example being the highly successful restoration of the Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, South Korea.

Adam Broadhead’s Daylighting website maps deculverting projects around the world as a means of sharing information on their outcomes and effectiveness. We spoke to Adam to find out more about this fascinating and innovative project.

Freshwater Blog: Not only have you been working on a PhD on deculverting urban rivers at Sheffield University, you’ve also put together the Daylighting project. Could you tell us a little about these projects and where you got the inspiration for starting them? Do they overlap and cross-pollinate each other?

Adam Broadhead: They are very much related. Initially, I was looking at the issues surrounding daylighting: what challenges and uncertainties are there in the evidence base that prevent funding and hinder projects? Although there had been some academic reviews on the evidence, most projects had little available evidence on their environmental, social and economic objectives and outcomes.

The Daylighting website gathers this information in one place, along with costs and drivers of projects and contact details. I’ve also been using a lot of Facebook and Twitter to spread the word among other professionals and the wider public about lost rivers and opportunities for opening them up – and by far the most common reaction is one of support.

The PhD work specifically focused on a particular aspect of this topic and arose from some literature from Zurich, Switzerland. Some streams and springs have not only been buried, but completed lost into the sewer system and flow to the sewage works.

My work has been to demonstrate that this happens, and develop methods to identify and predict where. If lost rivers affect water companies too, that means another key stakeholder and funding source to do daylighting to reduce sewer network costs, in addition to the wider flood risk, ecology and public space benefits.

The River Alt in Liverpool, daylighted in 1994, with how it looked before (bottom), and the mature, diverse landscape of today (top). Image: Adam Broadhead

What different benefits can daylighting such ‘lost’ rivers bring?

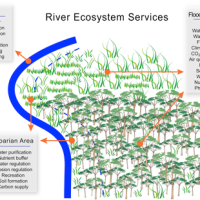

Buried watercourses receive no sunlight, and so can be ecological deserts to life in the water and around the river banks (fish, birds, insects, plants, mammals). The darkness and other modifications to the channel often prevent passage of fish just like weirs do. Opening them back up can bring back all of this ecology, when done properly.

Daylighted watercourses also have less of a flood risk due to underground blockages or collapse and it is easier to spot and tackle sources of pollution when you can see the water. People can see and enjoy the wildlife that daylighted streams support, with knock-on positive effects for health and well-being, education and recreation. Open watercourses can help to reduce the urban heat island effect and can (and are) being used to drive regeneration in downtown areas.

Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul, decorated for the Lotus Lantern Festival. Image: Emily Orpin

Where has daylighting been particularly successful?

There are so many good examples. One of the largest and most impressive is the Cheonggyecheon in Seoul, South Korea where miles of river were created through the city centre, with fountains and paddling areas in the artificial end, and open wildlife space in the more natural downstream end. One of my favourite examples, though, is the Quaggy River daylighting at Sutcliffe Park, London, which provides a flood storage wetland area, abundant wildlife, amenity space and land value boosts for the area.

You are based at Sheffield University. Does Sheffield have a network of ‘lost’ water?

Yes – Sheffield is a water city. Rivers, brooks and natural springs flow through and beneath the city, sometimes simply culverted (continuing to flow as rivers) such as through the “Megatron” culvert right beneath the station area; others, as my PhD work suggests, completely wiped off the map and now part of our Victorian sewer system.

Adam sampling sewer water in Sheffield at 3am in search of lost urban streams

What happens in the process of daylighting a river? Is it a relatively time and money intensive process? I would imagine that it’s not always easy to ‘reclaim’ waterways through urban areas?

There are capital costs for the engineering to remove the ‘lid’ off the river, plus additional restoration to the channel shape to renaturalise it. Sometimes in old industrial areas there will be a lot of contaminated land and soils, escalating costs and limiting the work that can be done (such as the Darwen at Shorey Bank).

Most of the time, it will be necessary to do some additional flood risk work – often that is the main initial driver and funding source for projects (rather than ecological improvements) – and this will require additional investment. A big cost is the land itself – quite often it will be occupied by buildings or roads, some of which we wouldn’t want to get rid of.

The good news is that the costs and benefits often do stack up to make daylighting a worthwhile investment – we’ve seen daylighting in downtown New York on the basis of that regeneration benefit alone. And there are many much smaller culverted watercourses that could be opened up far more cheaply by local contractors – a fear of the unknown contributes to costs being greater than necessary in my opinion.

Buried underground for nearly a century, the Saw Mill River in Yonkers, NY in the USA has been daylighted in a $19 million programme, providing new habitat for a variety of life including the migratory American eel. Image: Wikipedia.

How easy is it to work with governments, local authorities and water companies to convince them of the value of daylighting rivers? Is the process helped or hindered by any environmental policy?

All of those authorities support daylighting lost rivers, either implicitly as part of wider Water Framework Directive or Floods Directive legislation, or explicitly with specific deculverting policy. I’d still like to see daylighting lost rivers feature more strongly in these policies though – the issue can end up getting “lost” itself amongst all the other priorities and cheaper measures for easier projects. This is a shame because we are missing out on some really transformative and impressive improvements to our towns and cities.

There are sadly still policies that allow rivers to be newly culverted to allow development – I’d like to see our Environment Agency and Natural England agencies to be decoupled from present political drivers, giving them back their “teeth” to properly tackle and object to such development where they can. But that is getting political…

Another big challenge is strengthening the evidence base by collating data and results from other projects, demonstrating that rivers can be daylighted for multiple benefits even in highly constrained sites, and that the costs can be outweighed by the long-term environmental, social and economic gains. Identifying benefits for private sector developers to open up buried watercourses themselves, or for water companies to do it to help reduce their own operating costs, will help too. I hope that both the Daylighting website and my PhD work will contribute to a step in this direction.

Looking for traces of the underground River Fleet in London. Image: David Busch, Flickr

How would you go about looking for ‘lost’ rivers in your own town? Where would you look: historic maps, street and place names, topography?

All of the above! My research showed that no single piece of evidence is perfect all the time in all places. Gather whatever you can. Old maps are a great start, often available in high detail from the 1850s onwards, and sometimes much older. Street names etc are good clues to focus your search – Springvale Road, Wybourne, Riverdale Street, Bower Spring: the clues are in the name.

If you have access to data and open source GIS software, topography data can tell you the routes of old valleys. I’ve also had a lot of information from old historic text books referencing old streams and springs, old photographs and paintings, and from local people who remember the watercourse first-hand or know of springs flowing through their gardens or basements.

Finally, exploring ‘lost’ rivers in urban areas has become increasingly popular in recent years: what do you thinkis it about them that captures people’s attention?

I can’t speak for everyone, but for me there is something fearful about the unknown beneath us. That fear entices me and intrigues me. But equally, the underground culverts are marvels of engineering in so many cases. My favourites are the neat engineering of Joseph Bazagette’s Victorian London sewers that were formed from old watercourses.

I know a lot of people are going urban exploring down culverts and sewers. I am pleased they do because of the images and information and interest that comes from it, but I can’t recommend it because many inexperienced people go exploring and it can be really dangerous. Perhaps the thrill is what draws them to it.