Can the EU Nature Restoration Law help make Europe’s rivers flow more freely?

After months of debate and revisions the EU Nature Restoration Law was approved by the European Parliament in late February. The law represents an ambitious step towards restoring Europe’s depleted ecosystems, requiring EU countries to restore at least 20% of their land and sea by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

The EU Nature Restoration Law is a significant response to the fact that over 80% of European habitats are in poor condition and in need of restoration. Moreover, it foregrounds the vital roles that nature plays in supporting our lives, whether through food security, flood protection or water supplies. On a continent increasingly stressed by the effects of the climate emergency and economic crisis, it offers a hopeful vision of fostering more sustainable and resilient societies and economies in the future.

Despite significant lobbying from opponents, the law was approved in the European Parliament with 329 votes in favour, 275 against, and 24 abstentions. It will now move to the European Council for adoption ahead of its ratification into law. European countries will then need to submit – and regularly update – national restoration plans to demonstrate how they will restore their lands, seas and freshwaters over the coming decades.

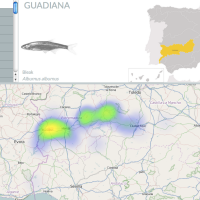

A key element of the Nature Restoration Law is its commitment to restoring 25,000km of free-flowing rivers across Europe by 2030. Free-flowing means that a river can flow without major obstacles like dams, hydropower plants and weirs. Such obstacles can significantly alter the flow and course of a river, which can shift how it responds in times of flood and drought. Moreover, they can restrict the movement of fish and insects along a river’s course, which can particularly impact the health of migratory fish populations like salmon and sturgeon.

Free-flowing rivers are not only good for nature, they also represent a break from decades-old thinking on river management, which sought to channel, store and control water flows in order to support human activities. All across Europe, this new thinking has resulted in widespread dam removal, designations of ‘Wild River’ National Parks, and protests against hydropower construction in recent years.

The adoption of the Nature Restoration Law adds further momentum to this growing movement. This work is timely and much-needed: research suggests that there are over 1.2 million barriers fragmenting European rivers, with more than 156,000 of these being obsolete. Such obstacles are linked to significant biodiversity losses, including a 93% decline in freshwater migratory fish populations across Europe.

A team of European researchers have examined how the restoration of free-flowing rivers across Europe will be supported by the Nature Restoration Law. Their study – supported by BioAgora and published in WIRES Water – suggests that whilst there is significant potential for positive work, there remain a number of obstacles to overcome for the law to be a success for Europe’s rivers.

“It is important to underline that the Nature Restoration Law is an absolutely needed step in the right direction, also clearly confirmed from a scientific point of view,” said Dr. Twan Stoffers, lead author of the study, from IGB Berlin. “But river ecosystems are complex networks and their connectivity plays an important role. Hence, clear definitions of the central terms in the law are crucial for enabling efficient implementation.”

The research team – led by researchers from Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) in Berlin and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) in Vienna – identified seven key challenges for the implementation of the Nature Restoration Law in restoring free-flowing European rivers.

Challenge 1: Defining free-flowing rivers

Successful environmental laws are usually underpinned by clear legal definitions. This means that to restore free-flowing rivers, we need to better define what they are, and what they do for people and nature. The authors suggest the definition of: “free-flowing rivers as fluvial systems in which ecosystem functions and services are unaffected by any human-induced change in fluvial connectivity.”

Challenge 2: Prioritising interconnections across landscapes

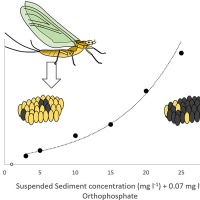

A river isn’t an isolated system: its water flows can ebb out onto floodplains, down into groundwater and out into the atmosphere. These interconnections with the wider environment change with time, as seasonal rhythms of flood and drought pulse along its catchment. The authors highlight that these dynamic interconnections need to be taken into account in river restoration. They suggest that defining minimum river section lengths to be restored is a good way of fostering these landscape-scale networks.

Challenge 3: Thinking big about ecosystems

Just as the water in a river isn’t confined to its course, neither are the ecosystems that it supports. So-called ‘meta-ecosystem’ thinking describes the ways that complex webs of life – fish, insects, mammals, birds, plants and more – are interconnected across land and water in a river catchment. The authors state that supporting large-scale ecological systems in Europe’s rivers requires significant collaboration between people and institutions across national and regional borders.

Challenge 4: Making sure free-flowing rivers benefit biodiversity

Two of the key strategies for restoring free-flowing rivers through the Nature Restoration Law are removing barriers such as dams and weirs, and restoring natural flow dynamics across floodplains that have been cut-off by artificial structures. The authors highlight that whilst these strategies are valuable, they need to be carried out in areas which can significantly benefit the health and diversity of river ecosystems. They suggest a need for a prioritisation process which highlights where restoration activities can best boost biodiversity across the continent’s rivers.

“Restoring an additional 25,000 km of free-flowing rivers by 2030 will not suffice to halt the decline of freshwater biodiversity, let alone reverse it,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig, co-senior author from IGB Berlin. “Due to the relatively small number of rivers to be restored, the implementation should focus on areas where restoration efforts will result in the most substantial improvements to ecological conditions, freshwater resources, and ecosystem services. In fact, it makes little sense to prioritise restoring degraded systems while still degrading near-natural or pristine systems at the same time.”

Challenge 5: Bringing people into the process

Rivers across Europe have been misused and neglected for decades because they have been narrowly viewed as a resource to power extractive industries, intensive agriculture and urban development. This has led to many rivers being trapped in concrete channels, their flows stilled and shrunken, and the webs of life they support hidden from view. The authors state that this needs to change. Bringing European rivers back to life is not only about restoring biodiversity, but also putting people at the heart of the change. This means both communicating the needs for healthy, free-flowing river systems to wide audiences, but also – crucially – listening to people who live and work in river catchments and considering their needs.

Challenge 6: Resolving conflicts with other European policies

The ways in which rivers have been widely neglected by human activities is also reflected in European policy. The authors argue that conservation and restoration efforts are not given the same priority in European policy as competing interests such as agricultural production (e.g. through the Common Agricultural Policy) or hydropower generation (e.g. through the Renewable Energy Directive). They state that there is a pressing need for the Nature Restoration Law to showcase how economic interests can be balanced (and made more sustainable) with environmental goals

“A law can only be as good as its practical implementation,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig. “We already see that with the Water Framework Directive, aiming at reaching the good ecological status or potential of water bodies. Despite turning into force over 20 years ago, the implementation deficit is still huge. But to give it a positive spin: the Nature Restoration Law could be a booster and role model for the Water Framework Directive activities, if its implementation is done right.”

Challenge 7: Mapping new approaches to monitor and manage river systems

As we’ve seen, the Nature Restoration Law is hugely ambitious, but its goals of restoring free-flowing rivers across Europe face a number of challenges. The authors identify the potential of new technologies such as environmental DNA (or eDNA) to help support how rivers are governed and managed through better ecological monitoring. In short, if new environmental thinking on large-scale landscape and ecosystem interconnections is to be embraced, there is the need for innovative new ways of monitoring and managing their dynamics across river systems.

The new study provides an invaluable road-map to guide European environmental policy makers and managers in the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law over the coming months and years.

///

Comments are closed.