84% of global freshwater species populations lost since 1970: can we ‘bend the curve’ of this trend?

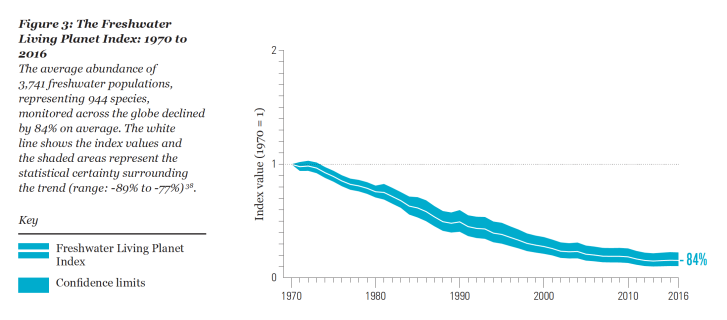

Global populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish have, on average, declined by two-thirds since 1970, according to the latest WWF Living Planet Report, released earlier this month. Continuing the trends shown in past reports, freshwaters are particularly imperilled: with 84% of global freshwater species populations lost between 1970 and 2016.

The bi-annual Living Planet Report tracks trends in global wildlife abundance, based on data from 21,000 populations of more than 4,000 vertebrate species. Population declines in freshwater ecosystems – which equate to an average annual loss of 4% globally – were higher than those in terrestrial and oceanic environments.

Significant declines in global freshwater species populations

WWF have published a ‘Deep Dive into Freshwater’ document looking at the stark findings of the Living Planet Report, and outlining ways to support global freshwater conservation in their wake. The publication states that population declines are particularly acute among freshwater amphibians, reptiles and fishes. Whilst freshwater population declines have been observed globally, they are most severe in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The drivers of these declines include habitat degradation, pollution, over-exploitation, invasive species and sand mining. These pressures are not always adequately managed in a large-scale, cross-boundary way by conservation schemes. The report suggests that large ‘megafauna’ species are particularly threatened, as their populations are less resilient to environmental pressures. One stark example is the spawning population of the Chinese sturgeon in China’s Yangtze river, which declined by 97% between 1982 and 2015 due to dam construction.

Lost wetlands and fragmented rivers

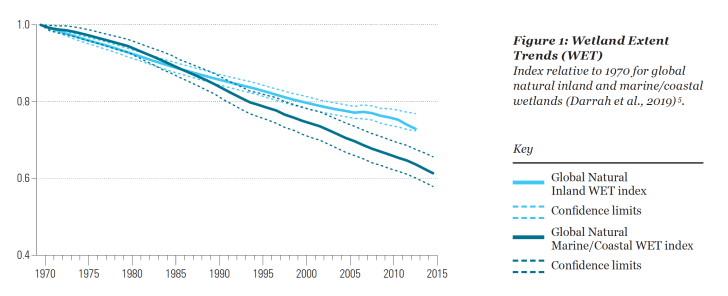

The ‘Deep Dive’ publication identifies two key trends in freshwater ecosystem change which are likely to be contributing to freshwater population declines. First, it states that nearly 70% of global wetlands have been lost since 1900, and they are still being destroyed at a rate (around 1.6% per year) three-times faster than rainforests. Wetlands are crucial ecosystems for many endangered and endemic species, and provide many benefits such as natural flood prevention to human communities. However, they are being widely drained, dammed and dyked across the world, often to support crop and livestock production.

Second, a 2019 mapping of millions of kilometres of global rivers revealed that only one-third of the world’s 242 longest rivers (more than 1000km in length) remain free-flowing. The majority of the remaining free-flowing rivers are found in remote areas of the Arctic, Congo and Amazon basins. The construction of dam and hydropower infrastructure can significantly alter the flows of water, sediment and nutrients through a river catchment, and inhibit the movement of migratory species. Despite increasing global attention to the issue, proposals for new dam constructions continue apace on many large river systems across the world.

Bending the curve of freshwater biodiversity loss?

In a blog posted earlier this week, Dean Muruven, WWF Global Freshwater Policy Lead, urges everyone working in freshwater conservation to pause and reflect on the results of the Living Planet Report. He writes, “If you have been an academic championing freshwater conservation throughout your career, you may have to finally accept that all those important (and they are critically important) science papers and commentary pieces in top academic journals have not had the expected impact. Instead of helping to save species, they have largely catalogued their decline. Maybe it’s time to start focusing on policies as well as papers — and perhaps even protests.”

Muruven argues that it is time for freshwater conservationists to radically improve how they communicate their work to wider audiences. He suggests that this involves “stepping out of the freshwater conservation bubble and having those difficult conversations with those that share a different a world view from us — to pave the way for learning and partnerships.”

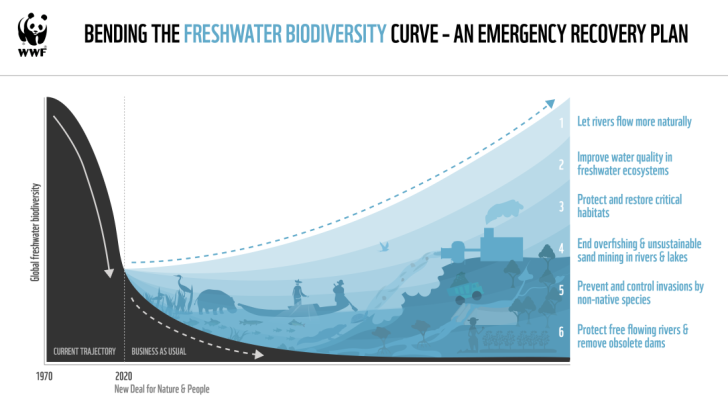

The WWF’s current approach to fostering widespread dialogue and action on tackling the freshwater biodiversity crisis centres on their Emergency Recovery Plan for Freshwater Biodiversity. The plan, discussed in a blog back in February, is based on six key themes.

They are: letting rivers flow more naturally; reducing pollution; protecting critical wetland habitats; ending overfishing and unsustainable sand mining in rivers and lakes; controlling invasive species; and safeguarding and restoring river connectivity through better planning of dams and hydropower.

The authors of the Emergency Recovery Plan suggest that unless significant collective action is taken to ‘bend the curve’ of freshwater biodiversity loss globally then the downward trends of species loss and ecosystem degradation will continue apace. The time to tackle this crucial issue is now: the key question, as Muruven puts it, is, “are we capable as a freshwater community of coalescing around the Emergency Recovery Plan for the next five years and collectively have a go at bending the curve?”

+++

Comments are closed.