Are Pablo Escobar’s hippos restoring ‘lost’ ecological processes to Colombian freshwaters?

When Pablo Escobar died in 1993, the drug kingpin left behind – amongst other things – a private zoo on his Hacienda Nápoles estate in northern Colombia. Whilst Escobar’s elephants, lions, giraffes and other animals were transported to other zoos when the estate was seized by the Colombian government after his death, four hippopotamuses were left behind.

The hippos – of which Escobar was said to be particularly fond – were deemed too dangerous and aggressive to move, and were left where they were. As the estate became neglected and overgrown, the hippo population at Hacienda Nápoles grew, gradually colonising artificial lakes and the Magdalena River.

It is now estimated that there are between 50 and 80 feral hippopotamuses living in Northern Colombia, with sightings of the animals taking place nearly 100 miles away from Hacienda Nápoles. One study suggests that by 2050, the wild Colombian hippo population could rise to between 800 to 5,000 animals.

Hippos are not a ‘native’ species in Colombia: there is no historical record of their presence here, or indeed anywhere in the Americas. The Hacienda Nápoles hippos have thus been called “the world’s largest invasive animal.”

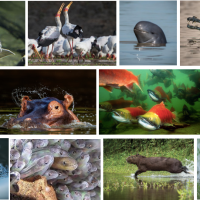

There are ongoing debates about the ecological impacts of the hippo poplution on freshwater ecosystems around Hacienda Nápoles. Hippos are ‘ecosystem engineers’, meaning their activities modify and maintain the environments in which they live.

In Africa, this can have positive ecological impacts: hippos bring significant amounts of nutrients in freshwater habitats by depositing faeces after grazing on surrounding grasslands, often supporting aquatic biodiversity. However, too much hippo faeces can cause water bodies to become toxic and eutrophic, and the sediment they stir up can further reduce water quality.

Either way, it appears that, for now at least, the Hacienda Nápoles hippos are here to stay – not least because removing them would be such a difficult and potentially dangerous operation. However, an innovative new study suggests that despite their ‘invasive’ tag, the Colombian hippos may be restoring ecological processes which have not been present for over 11,000 years to the freshwaters they colonise.

Writing in PNAS, a research team led by Erick Lundgren, argue that introductions of large herbivores – such as the Colombian hippos – have restored ecological processes relative to those found in the Late Pleistocene (roughly 130,000-11,000 years ago) in a number of landscapes globally.

The authors argue that the hippos share numerous ecological traits with an extinct giant llama species, Hemiauchenia paradoxa, which once grazed Colombian grasslands. The hippos also share traits and habitat with a large semi-aquatic rhino-like mammal called Trigonodops lopesi.

The authors compared key ecological traits such as body size, diet, fermentation type and habitat in herbivore species which lived before the widespread Late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions, more than 11,000 years ago.

“This allowed us to compare species that are not necessarily closely related to each other, but are similar in terms of how they affect ecosystems,” Lundgren, a PhD researcher at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Centre for Compassionate Conservation (CfCC), said. “By doing this, we could quantify the extent to which introduced species make the world more similar or dissimilar to the pre-extinction past. Amazingly they make the world more similar,” Lundgren added.

In neither case do the Colombian hippos share all their ecological traits with their extinct counterparts. The giant llama (Hemiauchenia paradoxa) did not live in aquatic habitats, and the rhino-like mammal (Trigonodops lopesi) does not share the hippos’ digestion characteristics.

The point the study authors make, however, is that the ‘invasive’ Colombian hippos and other species across the world are restoring ecological processes to landscapes where they have been lost due to the extinction of large herbivores thousands of years ago. A process-led approach to environmental restoration has been advocated by initiatives such as the Pleistocene Park in Northern Siberia.

As is often the case in debates over the ‘nativeness’ and ‘invasiveness’ of different species, the impulse to look to historical ecosystems to set baselines for conservation and restoration can often reveal a complicated and dynamic ecological reality. Viewed through the lens of the study, the ‘invasive’ hippos could be understood as participating in an inadvertent functional ‘rewilding’ of the Colombian freshwater ecosystems.

Senior author Dr. Arian Wallach from the UTS CfCC says, “We usually think of nature as defined by the short period of time for which we have recorded history but this is already long after strong and pervasive human influences.”

“Broadening our perspective to include the more evolutionary relevant past lets us ask more nuanced questions about introduced species and how they affect the world. We need a complete rethink of non-native species, to end eradication programs, and to start celebrating and protecting these incredible wildlife,” Dr. Wallach said.

+++

Comments are closed.