The partial success of the Water Framework Directive: a result of implementation rather than intent?

The River Danube at Vác in Hungary. The Danube river basin covers 10% of continental Europe. Image: Kikasz | Flickr Creative Commons

The European Union Water Framework Directive (WFD) requires all EU Member States to improve the quality of their surface and ground waters to ‘good’ ecological and chemical status or potential. However, despite some positive progress since its adoption in 2000, nearly half of EU surface waters still do not reach good ecological status.

A recent study led by Dr Nick Voulvoulis, Professor in Environmental Technology at Imperial College’s Centre for Environmental Policy, investigated why the ‘great expectations’ that came with the WFD have not yet been fully realised.

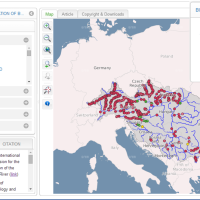

The research was undertaken through GLOBAQUA, an EU FP7 research project, which studies the effects of multiple stressors on aquatic ecosystems under water scarcity. The project is generating a range of water policy and management recommendations on how emerging threats to aquatic systems could be mitigated.

Writing in Science of the Total Environment, Voulvoulis and colleagues reviewed EU policy documents to identify how the WFD has been interpreted in environmental management, focusing on its intentions and how they have been applied across Europe. They suggest that there is a widespread absence in environmental policy and management of the integrated ‘systems thinking’ that the WFD was grounded on. In essence, they suggest that the partial success of the WFD is largely due to its implementation rather than its intention.

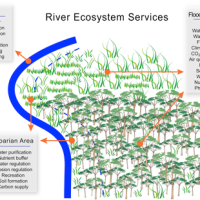

One systems approach in the WFD is the Drivers-Pressures-State-Impacts-Responses (DPSIR) framework, which draws links between environmental effects, their causes and management. Others include ‘catchment-based approaches’ and ‘integrated river basin management’, which call for aquatic systems to be managed as part of a linked landscape-scale system including terrestrial, freshwater, transitional and groundwater ecosystems.

Voulvoulis and colleagues suggest that the ideals of such systems approaches can be lost when the WFD is applied at national level (for example, in Italy in 2012). They suggest that some EU member states have struggled to characterise and monitor aquatic pressures, impacts and economic effects in ways that support catchment-based management.

A key shortfall they identify is in the monitoring of multiple pressures and their impacts, and how this translates to effective management (see also the 2012 Fitness Check of EU Freshwater Policy for similar findings). The authors suggest that ecological monitoring of aquatic systems can too often be focused on the ‘symptoms rather than the cause’ of poor status, identifying individual elements (such as pollutants) without adequately managing their sources in the wider landscape system.

The authors cite the 4th WFD Implementation Report from 2015, which shows that for 21 out of 27 Member States there were no clear links between aquatic pressures and their WFD Programme of Measures (i.e. their environmental management approach). Similarly, 23 out of 27 Member States had not effectively implemented a gap analysis to develop appropriate water management measures.

In short, Voulvoulis and colleagues suggest that the limited success of the WFD is due to the “reductionist implementation of a systems directive”. They identify common misunderstandings of the Directive’s core principles as potential barriers to its successful implementation.

“EU water policies are still in need of the paradigm shift towards the WFD aspirations, embracing its holistic, integrated and interdisciplinary approach,” says Professor Voulvoulis. “Catchments are composed of highly interdependent human and natural systems and due to this complex web of interactions; WFD implementation based on catchment management was never going to be an easy process.”

Professor Voulvoulis states, “The WFD offers a platform for system-level shifts that need to take place, and unless it is recognised for this, a real opportunity for collective action will be missed. It is clear that implementing the WFD like any other directive is not going to work. Unless current implementation efforts are reviewed or revised, allowing the Directive to deliver its systemic intent in order to reach its full potential, the fading aspirations of the initial great expectations could disappear for good.”