SOLUTIONS Technologies 2030 workshop: trends and consequences of future chemical pollution

Guest post by Dirk Bunke, Susanne Moritz, Werner Brack and David López Herráez.

Can changes in the availability and use of water resources, population demography, technology, economy and climate alter the pattern of chemical substances released into the environment? Is it possible – at least to a certain degree – to predict future emerging pollutants?

The EU SOLUTIONS project address these questions based on scenarios impacting on freshwater chemical pollution. The project’s underlying objective is to suggest assessment tools and abatement options for emerging water pollution challenges.

SOLUTIONS workshop – Technologies 2030

The project’s first task on this ‘topic of tomorrow’ was to identify and examine patterns and trends in current chemical pollution. Following this initial analysis, SOLUTIONS scientists are now working with external experts in dedicated workshops to discuss economic, technological and demographic trends in society.

Last month, the SOLUTIONS project held a workshop titled ‘Technologies 2030’, which brought together a team of researchers and stakeholders to discuss the challenges of new and emerging chemical pollutants.

Innovations in technologies play a central role in enhancing the efficiency of processes and products. New materials are constantly being developed, and form the basis of the majority of new product innovations. Printable electronics, metallic matrix composites, technical textiles and switchable shading systems are only some examples. Does this automatically mean that we can expect parallel releases of new substances into the environment?

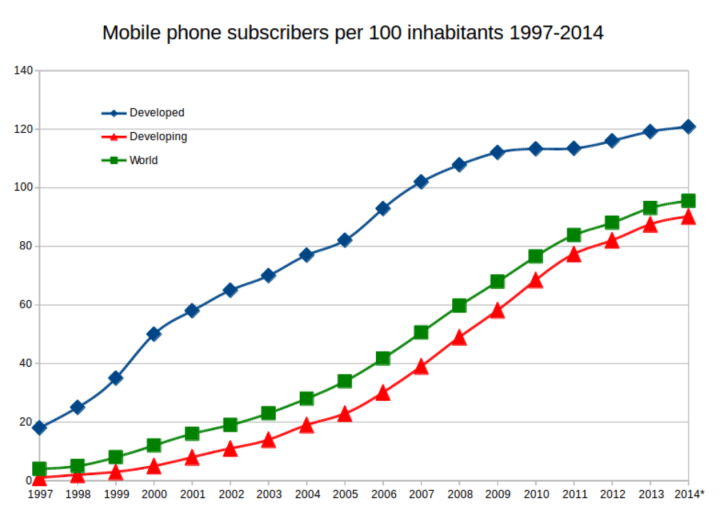

Mobile phone subscribers per 100 inhabitants distinguishing developed and developing countries. Figures for 2005-2014 taken from International Telecommunication Union – ITU. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The future of chemical pollution in freshwaters

The workshop’s systematic search for incipient trends, opportunities, challenges and constraints that might affect societal goals and objectives began with a “horizon scanning” presented by Michael Depledge. What is the future of chemical pollution in freshwaters? What will be the new and emerging pollutants, and where will they come from?

All predictions of future developments show a degree of uncertainty, nevertheless Depledge gave an overview about practical experience in scanning for global environmental issues. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology identified in a similar approach the following candidates as important new technological trends: Nano-Architecture, Car-to-Car Communication, Project Loon (connecting billions of people to the Internet), Liquid Biopsy, Megascale Desalination, Brain Organoids, Supercharged Photosynthesis and Internet of DNA.

Regarding future chemicals and potential pollutants, the key questions are: What kind of chemicals will we need in future worlds? In what amounts? In which regions of the world? From 1940 up to today, the amount of chemicals produced has increased several hundred folds. In part, consumption of chemicals can be directly predicted from product sales – for example, the trace elements needed for smartphones.

Existing chemicals

It is estimated that two-thirds of future chemical production growth will be as a result of already-existing chemicals. Parallel to the projected growth in chemical production, new approaches to reduce emissions come up. For example: automated agricultural vehicles in Precision Agriculture minimizing wastage of fertilizers, pesticides and other agrochemicals. However, at present, precise long-term visions about how the future in Europe and the world will look like with respect to new products and chemicals are still lacking.

New material developments

Approximately 70% of all product innovations in Europe are based on new material developments. Wolfgang Luther from the VDI Technology Center, Germany, presented an overview on the early identification of chemical aspects for innovative materials and technologies. Materials innovations comprise new substances, substance and material modifications (e.g. surface functionalization), new material combinations (e.g. multi-material systems, composites) and new application context of established substances.

A key driver for material innovations are substitutions. Substitutions may take place for different reasons: rare or cost intensive raw materials, hazardous and toxic substances, change to more sustainable technologies, change to better technical performance and/or cost reduction.

The VDI Technology Center has identified more than a hundred innovative technologies and materials, selecting 20 of them for a deeper analysis. They belong to the following six groups: new production technologies (such as 3D printing), electronics (such as OLEDs and printable electronics), construction and lightweight engineering, energy and environmental engineering (as organic photovoltaics), textile technologies and functional materials and coatings (as polymeric foals). Many of the 470 substances compiled for these new technologies were polymers, a class of compounds, which is not registered under REACH.

Energy supplies

One of the major developments in the near future addresses technologies for energy supply. As discussed by Andreas Müller from chromgruen and Jonas Bartsch from the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE, Germany, all technologies of energy transition, including energy production, storage and saving, come along with their specific chemical footprints, which require careful assessment.

Hydraulic fracturing (i.e. Fracking) might be the technology with the largest diversity of chemicals used involving more than a thousand individual compounds. Solar heat requires isocyanates for PU (polyurethane) foams and adhesives, organohalogen and organophosphorous flame retardants, and a range of metals and other inorganic materials.

Bisphenol A-based epoxy resins are used for rotor blades and might be emitted during manufacturing, use and dismission. Hydropower plants can be considered as stocks for legacy chemicals such as asbestos and polychlorinated biphenyls, which may be released to the environment as and when these plants are refurbished.

Photovoltaics

One of the key technologies of future energy production is photovoltaic (PV). A wide variety of designs have been developed to save the energy of excited electrons using a range of (mostly silicon-based) semiconductors. Apart from silicon semiconductors, organic solar cells using compounds of complex structure, such as fullerenes and hexalthiophene, dye-sensitized solar cells and mixed types are available but are not expected to replace silicon based PV within the next decade.

During use, the current technology shows only limited risk due to a low release potential. Recycling is desirable – for economic savings and pollution prevention. During production, typically hazardous substances are used. However, this takes place under “clean room conditions” with the aim of closed material cycles.

Nanotechnologies

Nanotechnology is another key enabling technology with potentially high benefits for social and economic development, yet which at the same time poses risks to the environment and human health. Both technological development and risk assessment have been interlinked in the Dutch project Nanonext (as presented by Annemarie van Wezel).

The project developed a specific method for Risk Analysis and Technology Assessment – termed RATA – including a specific tool set to check new business ideas for risks – really at the beginning. This “Golden-egg check” may be seen as an example for other novel technologies and is publicly available. Checking for risks in advance and minimizing them from the very beginning may become a selling point for novel technologies.

Horizon scanning at Technologies 2030

The SOLUTIONS workshop on “Technologies 2030” and their impact on future pollution highlighted the strongly chemical-related nature of many novel technologies including electronics, energy, nanotechnology and many more.

New compounds for novel technologies such as dye sensitized solar cells will come up but at the same time many already existing chemicals will be used. Thus, future patterns of pollution – in 2030 and onwards – will be a complex mixture of legacy chemicals, “forgotten” old chemicals which are released decades after their use, and new emerging substances.

It will be SOLUTIONS’s task to translate this finding into strategies for future environmental modelling and monitoring as well as for sustainable use of chemicals minimizing risks to freshwater ecosystems and human health.

Participants

Attendees from following institutions participated in SOLUTIONS “Technologies 2030”

Dirk Bunke, Susanne Moritz and Anton Biljan from Öko-Institut (Institute for Applied Ecology – Germany); Werner Brack, Rolf Altenburger and David López Herráez from the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research – UFZ; Michael Depledge from University of Exeter Medical School; Frank Sleeuwaert from the Flemish Institute for Technological Research – VITO, Annemarie van Wezel from Watercycle Research Institute/University Utrecht – The Netherlands; Andreas Müller from chromgruen – Germany, Wolfgang Luther from VDI Technology Center, Germany, Jonas Bartsch from Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems – ISE, Christiane Heiss from the German Federal Environment Agency, and Valeria Dulio from L’Institut National de l’Environnement Industriel et des Risques – INERIS, France.

Extreme events in running waters

A flooded street in Appleby, Cumbria. Image: Fiona Trott / Twitter.

Over the weekend, heavy rainfall in the north of England caused major flooding in Cumbrian and Northumbrian towns and villages. A Met Office rainfall gauge at Honister Pass in the Lake District recorded 341.4mm of rainfall between 1800 on the 4th and 5th of December, a new UK record for a 24 hour period. The heavy rainfall was partly caused by a persistent flow of warm, wet air from the West Atlantic Ocean, which is currently experiencing high sea-surface temperatures.

The floods have left homes and businesses flooded and without power, cut-off roads and train lines, and brought down trees and bridges. There are also likely to be significant ecological effects which may only be evident over time, for example if salmon redds in the upper reaches of the flooded rivers have been been destroyed. Responding to the floods, some commentators have called for better flood defences to be constructed, whilst others advocate the reforestation of the surrounding hills as a means of intercepting and buffering heavy rainfalls.

Commenting on the floods in Northern England, Professor Dame Julia Slingo, Met Office Chief Scientist, said:

“It’s too early to say definitively whether climate change has made a contribution to the exceptional rainfall. We anticipated a wet, stormy start to winter in our three-month outlooks, associated with the strong El Niño and other factors.

However, just as with the stormy winter of two years ago, all the evidence from fundamental physics, and our understanding of our weather systems, suggests there may be a link between climate change and record-breaking winter rainfall. Last month, we published a paper showing that for the same weather pattern, an extended period of extreme UK winter rainfall is now seven times more likely than in a world without human emissions of greenhouse gases.”

RNLI volunteers rescue stranded residents from flooded streets in Carlisle. Image: RNLI

Such extreme weather events are a natural feature of climate variability, and help shape the forms and functions of freshwater ecosystems, according to ecologists Mark Ledger and Alexander Milner from the University of Birmingham, UK. However, climate change is shifting the magnitude and occurrence of extreme weather events, and understanding their consequences for river and stream ecosystems is an key research priority.

In a newly published special issue of the journal Freshwater Biology, editors Ledger and Milner have compiled 14 articles which examine extreme events affecting river and stream ecosystems across the world, including heat waves, fires, droughts, heavy rainfall and floods, tropical cyclones, storm surges and coastal flooding.

The open-access issue contains reviews of existing scientific literature and observational and experimental case studies which synthesise knowledge of extreme events and their ecological effects on freshwaters, as a means of guiding future research and management.

Flooded fields around the River Test, UK in 2013. Image: Neil Howard | Creative Commons | Flickr

The collected papers suggest that the ecological impacts of single events such as catastrophic floods, droughts and heat waves are highly context dependent. Impacts can be both positive or negative, and are dependent on the magnitude and extent of extreme events and their timing relative to life cycles of the affected species (e.g. spawning salmon).

Not all extreme events generate extreme ecological impacts, but combinations of events that cause multiple stresses are likely to have the most adverse ecological consequences. Ledger and Milner suggest that long-term monitoring programmes and sensor networks are essential in describing rare and unusual events. Similarly, ongoing experiments (see the MARS experiments on Alpine streams, for example) are important in understanding the mechanisms of extreme events which are likely to get stronger and more frequent in the future.

Water and Climate Change at COP21 in Paris

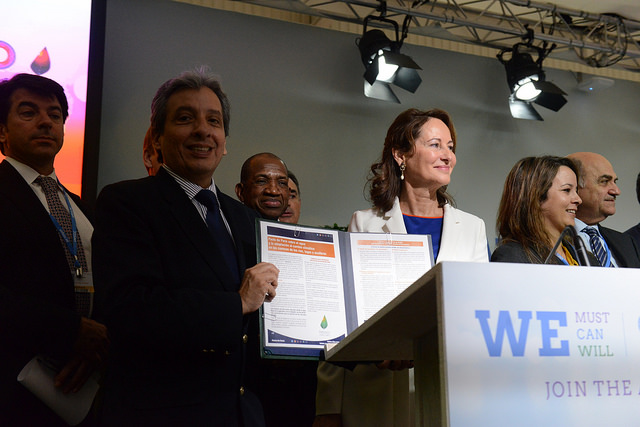

Delegates at the Water Resilience Focus event organised by the Lima to Paris Action Agenda. Image: UNFCCC

This week and next, governments, policy makers and NGOs from around the world are meeting in Paris to work towards a new international agreement on climate change intended to keep future global warming below 2°C. The 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (or COP21) takes place in a year declared the hottest on record by the World Meteorological Organisation.

Water is an key medium through which climate change affects human and non-human lives. Climatically-altered precipitation patterns, extreme weather events (and ensuing floods and droughts), and shifting water temperatures all contribute to alterations in the quality and quantity of freshwater available to humans, plants and animals in ecosystems around the world.

In particular, water scarcity is already posing threats to human livelihoods and freshwater biodiversity. The effects of such water stresses are often uneven, and disproportionately affect poor communities in developing countries with already arid climates (see this UN report, for example, pdf). As such, the interactions of climate change and water have important implications for human poverty alleviation and sustainable development.

The Paris Pact on Water and Climate Change Adaptation. Image: UNFCCC

Whilst some commentators suggested in the run-up to the Paris COP that water would be largely absent from negotiating tables, there have been some encouraging signs. This week, a coalition of national governments, river basin organisations, businesses and civil society groups announced the creation of the Paris Pact on Water and Climate Change Adaptation, intended to make global water systems more resilient to climate impacts.

Announced at a Water Resilience Focus COP event organised by the Lima to Paris Action Agenda on climate change, the Pact represents US$ 20 million in technical assistance and potentially over US$ 1 billion in funding for water and climate change adaptation. It will finance a coalition of almost 290 water basin organisations to implement adaptation plans, strengthen water monitoring and measurement systems in river basins and promote financial sustainability and new investment in water systems management.

The Pact is intended to improve water resources management as a means of making progress towards poverty reduction targets, and achieving sustainable development, for example through Sustainable Development Goals.

Negotiations at the Paris COP are ongoing, and early indications are that there is broad cross-governmental support for significant cuts to carbon emissions. However, UN analysis (pdf) of pre-COP governmental pledges suggests that projected emission cuts may not go far enough to limit increases in global temperatures to 2°C targets by 2100.

For MARS leader Daniel Hering, strong governmental commitments to limiting future climate change in Paris are important for ensuring the health and diversity of global freshwater ecosystems:

“The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions are unlikely to be sufficient for the 2°C target. Any further step in this direction would be a success. However, it is quite obvious that we will have to live with global warming of more 2°C that will greatly affect freshwater quality and quantity.

A bundle of measures to minimise the effects of climate change on freshwater ecosystems are required. In particular, this concerns agricultural practices. For instance, nutrients affect warmer freshwater ecosystems more strongly, so nutrient standards will need to be stronger. River water temperature can effectively be mitigated with woody riparian vegetation, so buffer strips are a key to enhance freshwater ecosystem quality in a warmer world. And agricultural practices saving water will be crucial in arid areas.”

Similarly, MARS scientist Steve Ormerod emphasises the importance of tackling linked climate and water systems during the Paris negotiations. Ormerod, Professor of Ecology at Cardiff University and Chair of Council of the RSPB, describes that whilst encouraging steps are being made, the negotiations face key challenges in promoting resilient and adaptive ecosystems under climate change:

“All the evidence we have is that freshwater ecosystems are among the most sensitive of all to climate change: we know that they are warming, that their patterns of floods and droughts are changing, and that their organisms are being affected. In the end, this is bad news for people – because freshwaters are the ecosystems that we depend on more than any other.

I’m very glad there is at least some emphasis on freshwater at #COP21 – for example the Paris Pact on Water and Climate Change Adaptation focused on making our freshwater ecosystems more resilient across very large areas of the world.

Conservation organisations such as the IUCN are pushing for the protection of “natural infrastructure” in river catchments and riparian zones as a means of making freshwaters more resilient. These concepts are supported by our own evidence – for example showing how riparian woodlands in temperate areas can ‘climate-proof’ rivers against future change.

But we should have no illusions about the magnitude of the challenge ahead. We are entering an epoch where pressures on freshwaters for water supply and for food production have never been greater. Sound, science-based management will become more critical here than anywhere, and we can only prevent catastrophe if scientists, policy makers and stakeholder engage fully in solving the problems of water – potentially our greatest problems of all.”

We’ll continue to follow the negotiations at the Paris COP and report back at the end of next week with their outcomes.

A Mediterranean river: the Fango Valley in Corsica. Image: Ole Reidar Johansen (Flickr | Creative Commons)

Rivers are often receptacles for substances used and emitted by humans living across their watersheds. Fertilisers, pesticides, pharmaceuticals and new substances such as microplastics and nanomaterials may be carried through drains and outflow pipes, along roads, pavements and fields, and through rock and soil to reach a river.

Here, pollutants can impair the health and functioning of the river ecosystem in a number of ways. Such effects are complex, and may occur in interaction with other stressors on the river ecosystem such as alterations of water flow and temperature, habitat loss, climate change and invasive species (see the recent MARS video on the subject).

The interactions and effects of such multiple stressor ‘cocktails’ on river ecosystems are still only partially understood by freshwater scientists. In this context, a new issue of the journal Science of the Total Environment features 44 scientific papers on multiple stressor effects on rivers, particularly focused on Mediterranean river basins and water scarcity.

The special issue, titled “River Conservation under Multiple stressors: Integration of ecological status, pollution and hydrological variability” is edited by Marta Schuhmacher from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili and Alicia Navarro-Ortega, Laia Sabater and Damià Barceló from the Spanish Council for Scientific Research Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research.

Between 2009-14, the editorial team were members of the Spanish government-funded SCARCE project, which assessed and predicted the effects of global environmental change on water quantity and quality in Iberian rivers.

The final SCARCE conference, held in October 2014 in Tarragona, was attended by many partners of the European Union funded GLOBAQUA project. Both projects have common interests in considering water scarcity as the main stressor in river systems. The Tarragona conference integrated many of the findings and data from the SCARCE project with ongoing GLOBAQUA activities, which in turn have been translated into journal articles in the new special issue.

There is a rich variety of articles in the issue, covering numerous different multiple stressors scenarios in ecosystems across the world, and assessing strategies for their experimental study and management. Earlier in the year, we covered a study published in the special issue by MARS scientists led by Peeter Nõges on biotic and abiotic responses to multiple stress.

You can read the special issue of Science of the Total Environment online here

UK Government taken to court over freshwater pollution

Crop spraying at Swaffham Lock, Cambridgeshire. Image: Hugh Venables, Creative Commons, from Geograph.

Today the Angling Trust, Fish Legal and WWF-UK have joined together in the High Court in London to challenge “a governmental failure” to prevent agricultural pollution in UK freshwaters.

The organisations have tabled a judicial review that argues that the UK government has failed to stop agricultural pollution from degrading 44 rivers, lakes and estuaries.

They argue that under the EU Water Framework Directive, the UK government is required to ensure that these freshwaters are in good health by the end of 2015. However, this deadline is unlikely to be met.

Campaigners are using the legal action as a means of pressuring the government to implement stronger environmental policies which promote the health and diversity of UK freshwaters.

Writing on the Angling Trust blog, Chief Executive Mark Lloyd attributes the poor health of many UK freshwaters (where, for example, only 17% of rivers are in ‘good health’) to a governmental failure to regulate agricultural practices:

“Rain landing on wet, compacted fields runs off the surface of the soil and into rivers, carrying with it slurry, soil, pesticides and fertilisers, all of which are lethal to fish and the invertebrates they eat. Badly maintained gutters allow rainwater from roofs to wash farmyard muck into drains. Broken pipes divert filthy water into streams. All these trickles add up to a mighty load of pollution. Just because it doesn’t come out of a big pipe doesn’t make it any more deadly to our aquatic wildlife. It’s often referred to as causing death by a thousand cuts.”

In particular, the coalition of organisations argue that the government has failed to implement any Water Protection Zones (pdf), the locally-specific policy approaches designed in 2009 to tackle agricultural pollution as part of River Basin Management Plans.

David Nussbaum, Chief Executive of WWF-UK argues that such decisions have overlooked the importance of freshwater ecosystems, which has prompted today’s legal action:

“This was an ideologically driven decision, taken behind closed doors, which contravened the Government’s public position. It also flies in the face of Defra’s own analysis which has repeatedly shown that relying on voluntary action by farmers alone will not solve the problem of agricultural pollution.

We believe the use of this ‘last resort’ doctrine to evade installing Water Protection Zones has not only been devastating for our protected rivers and wetlands but is also unlawful.

Worse still, with these specially protected sites continuing to be polluted it is baffling that Water Protection Zones are still not being used as we approach the December 2015 deadline – if this doesn’t count as a time of ‘last resort’, what does?”

Responding to the judicial review, a Defra spokesperson told The Guardian that:

“Rivers in England are the healthiest they have been for 20 years and we are committed to working closely with the farming community and environmental groups to further improve water quality. Over the next five years, we are investing more than ever to promote environmentally friendly farming practices to protect our rivers and lakes and support wildlife.”

In October 2015, the European Commission issued legal guidance that warned the UK government of its failures to implement EU water legislation, which could potentially lead to fines of millions of pounds a year.

Update 20.11.15: High Court rules that the UK government must evaluate the use of mandatory Water Protection Zones. Read more on the WWF website.

New film tells the story of Devon’s wild beavers

We wrote last year about the population of beavers found living on the River Otter in Devon in south-west England. These were the first wild communities of beavers found since hunting drove the animal to extinction in the UK in the 1700s. Earlier this year, the first baby beavers – known as kits – were born on the river (watch footage of them here).

The Devon Wildlife Trust, who monitor the beaver population, have recently released a short film documenting their work and the impacts of the animals on the local environment and communities. The film outlines how the Devon beavers are valuable ‘ecosystem engineers’ of new habitats in and around the river, have become a draw for ecotourists, and a focal point for local environmental education schemes.

A Swedish boreal lake. Image: Erik Jeppesen

The world’s lakes, rivers and reservoirs naturally emit carbon dioxide as part of the global carbon cycle. Recent scientific studies suggest that annual carbon dioxide emissions from inland freshwaters roughly equate to the total uptake of carbon by the world’s oceans.

However, a new study using extensive ecological data from 5,000 Swedish lakes suggests that ongoing changes in land use and climate are causing increased levels of dissolved inorganic carbon in northern boreal lakes, which in turn is causing the lakes to emit increasing amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Writing in Nature Geoscience, Gesa Weyhenmeyer from Uppsala University and colleagues observed that small lakes in southern Sweden emitted twice as much carbon dioxide as equivalent small lakes further north. The team documented that carbon dioxide emissions were highest in lakes with a significant number of ice-free days each year and high dissolved oxygen and nutrient concentrations (often as a result of agricultural runoff).

Co-author, and MARS partner, Erik Jeppesen from Aarhus University explains,

“Our work indicates that the release of carbon dioxide from lakes in Sweden will increase as the climate gets warmer, and as areas adjacent to lakes is used for agriculture in the place of forests.”

The burning of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, and scientific consensus is that the resulting increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations is causing increased global temperatures and other ongoing climatic changes.

The new study by Weyhenmeyer and colleagues shows that dissolved carbon from such emissions can travel through a watershed and ‘supersaturate’ lakes, which in turn causes them to emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. They suggest that carbon emissions from some of the boreal lakes in southern Sweden have reached levels comparable to lakes in tropical regions. In effect, this is a climatic feedback loop, where climate change drives further increases in CO2 emissions from freshwaters.

As a result, boreal lakes in northern latitudes of the world may become increasing sources of atmospheric carbon dioxide, a prospect that has consequences for global climate change, as Erik Jeppesen outlines,

“The findings worry us. There is great risk that as the climate warms in coming years, carbon dioxide emissions from lakes will increase significantly in the northern parts of Scandinavia, Russia and Canada. And, of course, these regions are where the vast majority of the world’s lakes are.”

For lead author Gesa Weyhenmeyer, the team’s findings have important implications for how we understand, and manage, boreal freshwater ecosystems as part of increasingly human-altered global climate systems,

“When we assess future emissions of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, it is important to know where the carbon dioxide comes from. Only with this knowledge can we find ways to reduce the release.”

Weyhenmeyer, G. A., Kosten, S., Wallin, M. B., Tranvik, L. J., Jeppesen, E., & Roland, F. (2015). Significant fraction of CO2 emissions from boreal lakes derived from hydrologic inorganic carbon inputs. Nature Geoscience, advance online publication.

SOLUTIONS for open-data publishing

Guest post by Steffen Neumann, David López Herráez and Werner Brack.

Since the earliest days of science, journal articles have been the centre of scientific communication. They are the source of information in which academics, policy makers and businesses know what is happening in – and can build upon – the important research in their field. With online publishing, scientists can now collaborate more than ever before, sharing not just brief overviews of their methodology and results in print articles, but also their full results, primary datasets and even interactive graphics, all as “supplemental data”.

Supplemental data may help make scientific research more reliable (as experiments can be easily and properly replicated and fact-checked), efficient (as similar datasets are shared across different users, rather than having to be created multiple times from scratch), and democratic and transparent (as expert statements are open to public scrutiny). Despite this, it can sometimes seem like authors, editors and reviewers currently neglect the huge promise of supplemental data.

This was one of the topics under discussion at last month’s second annual general assembly of the SOLUTIONS project. This EU funded project is an international collaboration of academics, policy makers and businesses, all working to solve the problems of chemical pollution in European rivers and lakes. Getting the most out of the relevant science is a hugely important aspect of SOLUTIONS’ work, and one in which good supplemental data could play a vital role.

After discussion at the recent general assembly, SOLUTIONS members Maria König, Miren López de Alda, Bozo Zonja, Francesco Falciani, Steffen Neumann and Tobias Schulze created a report entitled “What makes good Supplemental Data and how to get there?” The report gives the following advice to scientists on using supplemental data to create better science that can be used more effectively to support environmental protection.

Who uses supplemental data, and for what?

Perhaps one of the original aims of supplemental data was to add supplemental information that would not fit into the prescribed, say, eight pages of the main manuscript. In essence, these types of supplemental information are like an extension to the paper.

An important example of an area where supplemental data can really shine is meta-studies. These syntheses rely on being able to extract information from scientific studies in an efficient way. This could mean a lengthy process of contacting dozens of authors to obtain the required data. With good supplemental data, however, access can be instantaneous – making meta-studies not only better scientifically, but also cheaper and more efficient.

Another example is people searching for the best available method for a new study. Very often, journal papers report that some method performs this-and-that better than another method, or is faster, or cheaper, or all of these. Good supplemental information allows potential users to be able to make an informed, unbiased comparison of potential research methods.

Supplementary information can also allow a scientific finding to reach relevant audiences beyond the authors’ immediate peer group. A bioinformatics specialist, say, might be able to use the findings of a new chemistry study to create a better model of watershed pollution. However, he/she may not have the actual knowledge of chemistry necessary to make immediate sense of the article. Good supplementary information can provide the background information necessary for interdisciplinary (or even within-discipline) translation.

What is good practice for the use of supplemental data?

If you have any graphs or diagrams in your article, one of the first things you should have in your supplemental data is the actual data your figures are based on. This means someone else can reproduce the same graphics (even if this is only because they want it in another colour!) Spreadsheets or plain CSV files are the best format for this “real data”. Some useful recommendations for suitable archive formats can be found here.

If you’re reporting chemical compounds, you should provide an identifier – not only the name or CAS number. Deriving further chemical and physical properties from a name can be extremely tedious (or impossible) to do it unambiguously. Instead, you can use more detailed identifiers like PubChem CID or ChemSpider CSID, or descriptors like SMILES, InChI, InChIKey. If your datasets are too large for the publishing journal’s supplemental section, there are community-accepted repositories you can use, such as FigShare, Dryad and others.

If you’re reporting chemical compounds, you should provide an identifier – not only the name or CAS number. Deriving further chemical and physical properties from a name can be extremely tedious (or impossible) to do it unambiguously. Instead, you can use more detailed identifiers like PubChem CID or ChemSpider CSID, or descriptors like SMILES, InChI, InChIKey. If your datasets are too large for the publishing journal’s supplemental section, there are community-accepted repositories you can use, such as FigShare, Dryad and others.

The new SOLUTIONS report suggests that journal guidelines often give submitters little to no information about what to include in the supplemental data. So how do scientists learn to create good supplemental data?

The report suggests taking note of what works – and what doesn’t – in existing journal articles, and using in-house or departmental peer-review processes to check not just the proposed article, but its supplemental data too. Likewise, based on these recommendations, community advocacy could persuade journals to offer guidelines regarding minimum requirements and/or format their supplemental data should have. As a user-oriented, interdisciplinary project covering a huge range of chemical pollutants across the entire European Union, SOLUTIONS will be working hard to provide best practice examples of how supplementary data can be used to help science work better and faster to protect the environment.

Shaping the Future of UK Upland Environments

Upland communities of people, plants and animals that live on the UK’s high hills, lakes, rivers and moors are under increasing pressure. Whilst uplands form a large proportion of the UK’s land area (around 40%), they are often challenging places for communities – both humans and non-humans – to survive.

A lack of rural jobs coupled with the dwindling profitability of agricultural practices in many upland areas of the UK has put strain upon traditional communities. Upland areas are on the leading-edge of climate change in the UK, as the climate niches in which communities of plants and animals – many of them rare or endemic – live are moved slowly upwards in altitude until potentially little or no suitable habitat remains.

For example, upland peat bogs – a crucial store of carbon and regulator of water flows in the landscape – require cool, wet conditions to regenerate. Studies such as this 2013 report led by Professor Colin Prentice of Imperial College London suggest that future climatic change in the UK is likely to cause peat bogs to shrink – which when coupled with human degradation of peat bog landscapes through overgrazing and cutting is likely to have widespread effects on the ecological health of the wider upland environment.

As the figure below shows, upland landscapes provide a range of important ecosystem services to humans and support unique assemblages of plants and animals, making their ongoing sustainable use and management a key issue.

A new report led by the DURESS Project based at Cardiff University in Wales assesses the potential impacts of four different upland land-use scenarios on UK upland communities towards 2050. Funded by the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Sustainability (BESS) programme of the Natural Environment Research Council, the report assesses the consequences of four possible scenarios for UK upland landscapes over the next 35 years: Agricultural Intensification; Managed Ecosystems; Business as Usual; and Abandonment.

The scenarios were developed through analysis of the drivers of environmental change, both local (e.g. food markets, farming practices and hydro-schemes) and global (e.g. climate change, global food and timber markets and EU environmental policy), and the probabilities for their different paths of development over the next 35 years. These projected scenarios were supported by a process of ‘backcasting‘ in which historical environmental changes to the uplands since 1945 were analysed.

Each of the four projected scenarios has different environmental drivers and outcomes. The Agricultural Intensification scenario is projected to occur if global food security forces UK policy makers to focus on production, making hill farming an important contributor to the national livestock industry and limiting environmental protection to comply with the demands of the market. Here, riparian zones along rivers are likely to be removed to create more grazing land, alongside an increased input of fertilisers, chemicals and pesticides into upland rivers: creating new cocktails of multiple stress on aquatic life.

The Business as Usual scenario is projected where UK environmental policy aims to balance the aims of agricultural productivity and environmental protection. Here, upland farming does not contribute to UK food security, and environmental protection is based on a limited amount to small areas of land such as national parks and protected areas, areas with high tourism value, or areas requiring specific protection to meet regulations. Agri-environmental schemes are likely to help improve the health and diversity of upland rivers, but there will be difficulties in creating connected, landscape-scale environmental management schemes.

The Managed Ecosystem scenario is projected where carbon and biodiversity management becomes the dominant management paradigm in upland landscapes and environmental policy is focused on restoring peatlands, and expanding wetlands and woodland to regulate soil carbon loss and increase biodiversity. Whilst reliance on overseas areas for provisioning services (fuel, fibre and food) may increase, upland ecosystems will benefit from reductions in livestock grazing pressures and reduced erosion and pollution.

Finally, under the Abandonment scenario, existing upland policies become too costly to implement because of competition for public funds for other priorities and the lack of viable markets for products and services. The sustainability of farming enterprises decreases due to the loss of familial farm succession and poor uptake of new technology and practices. Declines in farming activity and upland livelihood opportunities leads to eventual agricultural abandonment. With grazing pressure removed, it is likely that upland ecosystems will undergo a process of ‘rewilding‘ to greater ecological health and diversity. (although as many recent studies have shown, the tangents of such environmental change are likely to be complex and difficult to predict).

DURESS is a project focused on promoting diversity in upland rivers as a means of improving their ecosystem service sustainability (watch their new Shaping Our Future film above). As such, river ecosystems are placed at the centre of the projected scenarios in the report, as a means of informing environmental managers on upland decision making. For each scenario, maps are created to show where land cover change would occur, the magnitude of this change, and its likelihood.

Rather than offering firm recommendations, the new Upland Scenarios report is framed as a ‘stock-take’ of ongoing DURESS research, part of which will inform the MARS catchment modelling work. It suggests that UK upland economies – particularly farming – are fragile and heavily dependent on national and European subsidies to continue. As such, the report ends with the question of whether rural economies can be managed by UK government policy to promote ecosystem services such as water resources, flood management, carbon sequestration, renewable energy and biodiversity. Balancing such environmental goals with issues of dwindling and aging rural populations, fragile economies and ecosystems gradually affected by climate change is likely to pose significant future challenges for UK policy makers and environmental managers.

Flows of water in rivers and streams across the UK are diverted over, under, through and around many different obstacles. Some of these are formed naturally – for example waterfalls – whilst others are human-constructed, such as dams, sluices and weirs.

As we’ve discussed in a number of posts (here and here, for example), whilst such human-made obstacles can have societal benefits (such as hydropower generation), they often have negative ecological effects: fragmenting fish migration routes, causing bank erosion, changing habitats and altering water and sediment flows.

An innovative new smartphone app has recently been released to allow members of the public to log the location and type of river obstacles – both natural and human-made – in UK rivers. River Obstacles has been jointly developed by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Rivers and Fisheries Trust for Scotland (RAFTS), the Environment Agency (EA) and the Nature Locator team.

An innovative new smartphone app has recently been released to allow members of the public to log the location and type of river obstacles – both natural and human-made – in UK rivers. River Obstacles has been jointly developed by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Rivers and Fisheries Trust for Scotland (RAFTS), the Environment Agency (EA) and the Nature Locator team.

The free River Obstacles app allows river users such as anglers, canoeists and walkers to log the details and submit photographs of obstacles such as dams and weirs. The data from these ‘citizen hydrology’ submissions will help map obstacles in regions where there is currently very little information (such as in remote areas), or where obstacles have recently been built or damaged.

The crowdsourced data submitted through the app will allow environmental managers and policy makers to identify redundant human-made obstacles that can be removed from rivers, and prioritise improvements to other obstacles that will yield significant environmental improvements. Information on natural obstacles will also be used to determine the natural limits to movement for different species of fish.

Environmental data submitted by members of the public has been growing in popularity over the last five years or so in the ‘citizen science’ movement (see our interview with Helen Roy from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology on the subject).

Public sourced information on the natural world – increasingly facilitated by advances in mobile technology – has a number of potential benefits: for example, creating data for areas where scientists may not have sampled and engaging members of the public with processes of environmental monitoring and management (see another, older post on the subject from back in 2010).

This is the first time we’ve seen this technology used to crowdsource hydrological data, making River Obstacles an innovative and interesting initiative. We’ll keep you updated with its results.

River Obstacles

Download for iPhone and Android