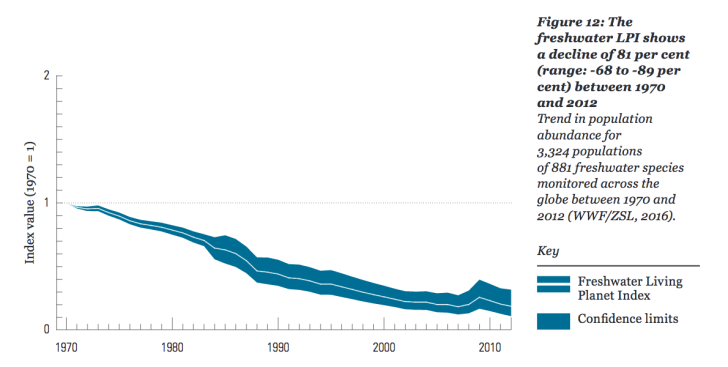

Freshwater species populations fall by 81% between 1970 and 2012

Freshwater biodiversity is decreasing across the world. Image: Mike Goehler | Flickr Creative Commons

Freshwater species populations dropped by 81% globally between 1970 and 2012, according to a new World Wildlife Fund report released today. According to the Living Planet Report 2016, this freshwater species decline is more than double that observed in land (38%) and marine (36%) populations, and population declines are predicted to continue in years to come.

Habitat loss is the major cause of declining freshwater species populations, as lakes, rivers and wetlands across the world continue to be abstracted, fragmented, polluted and damaged. As ongoing research into multiple stressors tells us, freshwater habitat loss can be caused by numerous pressures caused by human activities throughout entire catchments and river basins. Over-exploitation is another key cause of species loss, as fish and bird populations are harvested for food, and reptiles and amphibians collected for the pet trade.

The new Living Planet Report findings continue the downward trend reported in the previous 2014 report (see our blog here). What is striking about the findings – in context, that the world’s freshwater species populations have dropped by around four-fifths since the year in which the Beatles split up and the first Earth Day was held – is that in many parts of the world, 1970 is likely to be an already heavily-altered biodiversity baseline from which to observe subsequent trends. In effect, the Living Planet Report is reporting an 81% decline in many freshwater populations already subject to extinctions and declines prior to 1970.

In a section focused on rivers, the Living Planet Report outlines that almost half of global river flows are subject to alterations (e.g. abstraction or channel modifications) or fragmentation (e.g. weirs and dams). As work by and colleagues shows, such river modifications are likely to increase in the future, as around 3,700 major dam projects are proposed globally, many on previously lightly-altered river ecosystems.

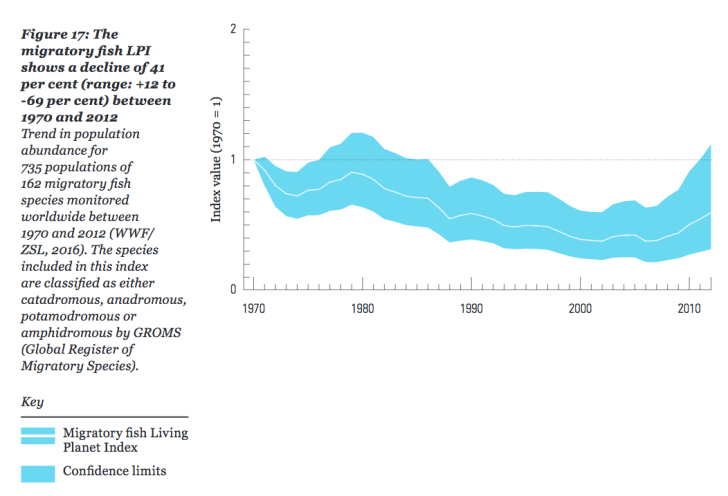

The graph above shows a 41% decline in migratory fish species between 1970 and 2012. Migratory species are particularly affected by fragmentation of river courses, as their natural migration routes are likely to be blocked or impaired – which in turn affects their spawning success, and the ongoing health of their populations. The upturn in the population trend from the mid-2000s onwards may be interpreted hopefully: a result of environmental policy in regions such as Europe where water quality has improved, and fish passes have been widely installed (largely prompted by the Water Framework Directive).

However, it also highlights that the Living Planet Report is based on a reasonably small sample of global species (162 in total), and as such overall trends may be influenced by large increases in a small number of species (for example, the Atlantic salmon in UK rivers such as the Tyne), and may not adequately capture real-life global trends.

There is an inherent trade-off here, of course. Such biodiversity surveys and predictions are necessarily based on partial samples of the world’s wildlife. Despite its limitations, the Living Planet Report, gives the most comprehensive indication yet of global biodiversity trends.

According to the report, global populations of all fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles declined by around 58% between 1970 and 2012. This species loss across biomes is occurring at a rate of around 2% a year, and appears to show no signs of slowing down, despite global conservation efforts.

Marco Lambertini, Director General of WWF International stated:

“The richness and diversity of life on Earth is fundamental to the complex life systems that underpin it. Life supports life itself and we are part of the same equation. Lose biodiversity and the natural world and the life support systems, as we know them today, will collapse.”

The results of the new report were calculated using the Living Planet Index – a measure of the state of global biological diversity based on population trends of global vertebrate species. The index uses the Living Planet Database (LPD) which holds ongoing time-series data for over 18,000 global populations of more than 3,600 mammal, bird, fish, reptile and amphibian species, gathered from scientific journals, online databases and government reports. For the freshwater results, data from 3,324 populations of 881 freshwater species monitored across the globe between 1970 and 2012 was used.

Introducing the report, Johan Rockström from the Stockholm Resilience Centre frames the ongoing global species loss within recent debates over the designation of the Anthropocene – the proposed new geological epoch in which humans activity is a primary driver of Earth’s natural systems. Marco Lambertini suggests that the findings should be the catalyst for rapid and widespread cultural and behavioural shifts that work to “decouple human and economic development from environmental degradation.”

The report ends with a series of large-scale proposals for promoting sustainable development, including the transformation of economic, energy and food systems that promote unsustainable use of the environment.

Such solutions have an inherent tension – how to address rapid, ongoing biodiversity loss through national and global political systems that are often slow-moving and which continue to promote economic development alongside (or sometimes, instead of) environmental protection. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are highlighted as a framework for positive global political and economic change, and the upcoming Convention on Biological Diversity COP in Mexico in December potentially provides a global platform for political leaders to respond to ongoing biodiversity loss.

Reflecting on the report, Mike Barrett, Director of Science and Policy at WWF-UK said:

“For the first time since the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, we face a global mass extinction of wildlife. We ignore the decline of other species at our peril – for they are the barometer that reveals our impact on the world that sustains us.

“Humanity’s misuse of natural resources is threatening habitats, pushing irreplaceable species to the brink and threatening the stability of our climate. We know how to stop this. It requires governments, businesses and citizens to rethink how we produce, consume, measure success and value the natural environment.