We’re delighted to share the latest episode of the MERLIN podcast with you.

Join us on the banks of the Danube River in Austria to hear how ambitious restoration projects are helping free the river from human alterations. We meet Robert Tögel and Alice Kaufmann from viadonau and Silke Drexler from BOKU beside the river to hear about how restoring its banks and side-arms is helping benefit both people and nature. As the trio explain, this work is a process of ‘learning from the river’ to help create space for natural processes to return, whilst at the same time making sure that navigation routes along the river are not impeded.

Back in Vienna, we hear from Helmut Habersack in the recently-opened BOKU River Lab to find out how centuries of alterations of the river interact with emerging pressures from the climate emergency and plastic pollution. We speak to Piret Nõukas from the Research Executive Agency at the European Commission to get a wider picture of how freshwater restoration work in MERLIN fits in with wider EU environmental policies like the Green Deal. And finally, we hear from Eva Hernández, co-ordinator of the WWF’s Living European Rivers initiative to discuss the pressing need to restore rivers across the continent, and how the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law – if passed – could help achieve this goal.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

After months of debate and revisions the EU Nature Restoration Law was approved by the European Parliament in late February. The law represents an ambitious step towards restoring Europe’s depleted ecosystems, requiring EU countries to restore at least 20% of their land and sea by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

The EU Nature Restoration Law is a significant response to the fact that over 80% of European habitats are in poor condition and in need of restoration. Moreover, it foregrounds the vital roles that nature plays in supporting our lives, whether through food security, flood protection or water supplies. On a continent increasingly stressed by the effects of the climate emergency and economic crisis, it offers a hopeful vision of fostering more sustainable and resilient societies and economies in the future.

Despite significant lobbying from opponents, the law was approved in the European Parliament with 329 votes in favour, 275 against, and 24 abstentions. It will now move to the European Council for adoption ahead of its ratification into law. European countries will then need to submit – and regularly update – national restoration plans to demonstrate how they will restore their lands, seas and freshwaters over the coming decades.

A key element of the Nature Restoration Law is its commitment to restoring 25,000km of free-flowing rivers across Europe by 2030. Free-flowing means that a river can flow without major obstacles like dams, hydropower plants and weirs. Such obstacles can significantly alter the flow and course of a river, which can shift how it responds in times of flood and drought. Moreover, they can restrict the movement of fish and insects along a river’s course, which can particularly impact the health of migratory fish populations like salmon and sturgeon.

Free-flowing rivers are not only good for nature, they also represent a break from decades-old thinking on river management, which sought to channel, store and control water flows in order to support human activities. All across Europe, this new thinking has resulted in widespread dam removal, designations of ‘Wild River’ National Parks, and protests against hydropower construction in recent years.

The adoption of the Nature Restoration Law adds further momentum to this growing movement. This work is timely and much-needed: research suggests that there are over 1.2 million barriers fragmenting European rivers, with more than 156,000 of these being obsolete. Such obstacles are linked to significant biodiversity losses, including a 93% decline in freshwater migratory fish populations across Europe.

A team of European researchers have examined how the restoration of free-flowing rivers across Europe will be supported by the Nature Restoration Law. Their study – supported by BioAgora and published in WIRES Water – suggests that whilst there is significant potential for positive work, there remain a number of obstacles to overcome for the law to be a success for Europe’s rivers.

“It is important to underline that the Nature Restoration Law is an absolutely needed step in the right direction, also clearly confirmed from a scientific point of view,” said Dr. Twan Stoffers, lead author of the study, from IGB Berlin. “But river ecosystems are complex networks and their connectivity plays an important role. Hence, clear definitions of the central terms in the law are crucial for enabling efficient implementation.”

The research team – led by researchers from Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) in Berlin and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) in Vienna – identified seven key challenges for the implementation of the Nature Restoration Law in restoring free-flowing European rivers.

Challenge 1: Defining free-flowing rivers

Successful environmental laws are usually underpinned by clear legal definitions. This means that to restore free-flowing rivers, we need to better define what they are, and what they do for people and nature. The authors suggest the definition of: “free-flowing rivers as fluvial systems in which ecosystem functions and services are unaffected by any human-induced change in fluvial connectivity.”

Challenge 2: Prioritising interconnections across landscapes

A river isn’t an isolated system: its water flows can ebb out onto floodplains, down into groundwater and out into the atmosphere. These interconnections with the wider environment change with time, as seasonal rhythms of flood and drought pulse along its catchment. The authors highlight that these dynamic interconnections need to be taken into account in river restoration. They suggest that defining minimum river section lengths to be restored is a good way of fostering these landscape-scale networks.

Challenge 3: Thinking big about ecosystems

Just as the water in a river isn’t confined to its course, neither are the ecosystems that it supports. So-called ‘meta-ecosystem’ thinking describes the ways that complex webs of life – fish, insects, mammals, birds, plants and more – are interconnected across land and water in a river catchment. The authors state that supporting large-scale ecological systems in Europe’s rivers requires significant collaboration between people and institutions across national and regional borders.

Challenge 4: Making sure free-flowing rivers benefit biodiversity

Two of the key strategies for restoring free-flowing rivers through the Nature Restoration Law are removing barriers such as dams and weirs, and restoring natural flow dynamics across floodplains that have been cut-off by artificial structures. The authors highlight that whilst these strategies are valuable, they need to be carried out in areas which can significantly benefit the health and diversity of river ecosystems. They suggest a need for a prioritisation process which highlights where restoration activities can best boost biodiversity across the continent’s rivers.

“Restoring an additional 25,000 km of free-flowing rivers by 2030 will not suffice to halt the decline of freshwater biodiversity, let alone reverse it,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig, co-senior author from IGB Berlin. “Due to the relatively small number of rivers to be restored, the implementation should focus on areas where restoration efforts will result in the most substantial improvements to ecological conditions, freshwater resources, and ecosystem services. In fact, it makes little sense to prioritise restoring degraded systems while still degrading near-natural or pristine systems at the same time.”

Challenge 5: Bringing people into the process

Rivers across Europe have been misused and neglected for decades because they have been narrowly viewed as a resource to power extractive industries, intensive agriculture and urban development. This has led to many rivers being trapped in concrete channels, their flows stilled and shrunken, and the webs of life they support hidden from view. The authors state that this needs to change. Bringing European rivers back to life is not only about restoring biodiversity, but also putting people at the heart of the change. This means both communicating the needs for healthy, free-flowing river systems to wide audiences, but also – crucially – listening to people who live and work in river catchments and considering their needs.

Challenge 6: Resolving conflicts with other European policies

The ways in which rivers have been widely neglected by human activities is also reflected in European policy. The authors argue that conservation and restoration efforts are not given the same priority in European policy as competing interests such as agricultural production (e.g. through the Common Agricultural Policy) or hydropower generation (e.g. through the Renewable Energy Directive). They state that there is a pressing need for the Nature Restoration Law to showcase how economic interests can be balanced (and made more sustainable) with environmental goals

“A law can only be as good as its practical implementation,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig. “We already see that with the Water Framework Directive, aiming at reaching the good ecological status or potential of water bodies. Despite turning into force over 20 years ago, the implementation deficit is still huge. But to give it a positive spin: the Nature Restoration Law could be a booster and role model for the Water Framework Directive activities, if its implementation is done right.”

Challenge 7: Mapping new approaches to monitor and manage river systems

As we’ve seen, the Nature Restoration Law is hugely ambitious, but its goals of restoring free-flowing rivers across Europe face a number of challenges. The authors identify the potential of new technologies such as environmental DNA (or eDNA) to help support how rivers are governed and managed through better ecological monitoring. In short, if new environmental thinking on large-scale landscape and ecosystem interconnections is to be embraced, there is the need for innovative new ways of monitoring and managing their dynamics across river systems.

The new study provides an invaluable road-map to guide European environmental policy makers and managers in the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law over the coming months and years.

///

River restorationists from across Europe met last week in Vienna to discuss the progress of the European Green Deal MERLIN project. Over the course of four days, attendees – which included scientists, water managers, finance experts and investors – collaborated in discussions around the seventeen sites across Europe where MERLIN is working to kick-start river restoration with ambitious new approaches.

The discussions – held in the impressive surroundings of the BOKU River Lab – were well timed given the positive outcome of the latest European Parliament vote on the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law. MERLIN’s work in restoring rivers, streams, peatlands and wetlands across the continent through innovative nature based solutions will provide a vital platform to support restoration across Europe in the coming years and decades.

On the final day, attendees were taken on a trip along the banks of the Danube River, close to the Austrian border with Slovakia. Here, project partners from viadonau are working to reconnect formerly-dammed side arms of the Danube, and to renaturalise its banks. Their work aims to reintroduce more natural habitat and to reconnect the river with its floodplain. Attendees learnt about how this work can be balanced with the navigation needs of ships travelling along the Danube’s course.

“We’ve now been through almost two-thirds of this project, and it’s simply amazing to witness the positive energy of all our collaborators — MERLIN seems to increasingly hit the nerve,” said project co-ordinator Sebastian Birk. “We all want to contribute eagerly to changing the usual business. And with the positive vote on the Nature Restoration Law that coincided with the beginning of the meeting, the tone was somehow set for this memorable event.”

“I’m immensely impressed by the motivation of the partners and their willingness to learn – scientists learn about catchment restoration, catchment managers about finances, finance experts about science,” added project leader Daniel Hering. “MERLIN is one of the most satisfying projects I have ever been involved in.”

Watch this space for a new episode of the MERLIN podcast recorded at the meeting, which will offer an in-depth look at the restoration projects on the Danube, and the importance of MERLIN’s work to the Nature Restoration Law and European restoration more broadly.

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

MERLIN Innovation Awards celebrates state-of-the-art approaches to freshwater restoration at 2024 ceremony

The winners of the annual MERLIN Innovation Awards – which highlight cutting-edge solutions for freshwater restoration – were announced earlier this month. Entries from organisations across the world were assessed by an expert panel, and shortlists for the two categories – Service of the Year and Product of the Year – were compiled. Two winners were announced at a busy online ceremony on February 8th.

The winners of the Product of the Year are Planet Srl for their Mangrove Technology Platform, a modular planting system which facilitates the planting and growth of trees in arid regions without adversely depleting freshwater sources.

This is achieved in two key ways. First, a desalinisation system harnesses sunlight to convert saltwater into freshwater, which allows water from mangrove ecosystems to be used for irrigation. Second, an efficient irrigation system helps water the deep roots of the planted trees without wasting water.

Mangroves are one of the few forest ecosystems that can grow in hot and arid climates. Found across the Gulf of California in Mexico, the Middle East, Western Australia, subtropical Africa and Western South America, mangroves are vital ecosystems which support rich biodiversity and fisheries, and can lock up significant quantities of carbon from the atmosphere.

The Mangrove Technology Platform is designed to help support the restoration of these valuable forests in areas where environmental pressures from heat and drought are common. Supported by an innovative digital monitoring system, the Mangrove Technology Platform allows trees to be planted in marginal areas, which in turn reduces competition with farmers for fertile soil and freshwater supplies. Overall, this provides a valuable nature-based solution to help boost carbon sequestration in arid landscapes.

“In the face of escalating land degradation, aggravated by increasing aridity, traditional tree planting confronts challenges of poor tree survival rates,” said Giulia Berni from Planet Srl. “The Mangrove Technology Platform emerges as a transformative solution, specifically designed to address these bottlenecks. By leveraging abundant saltwater and regenerating dryland, the MTP sets a new standard in agroforestry, offering a low-entry barrier solution that directly tackles the challenges faced by tree planting providers and organisations involved in carbon farming.

“With a sharp focus on resolving water scarcity, soil degradation, and low tree survival rates, the MTP aligns precisely with the critical needs of its customers, providing a sustainable pathway to scale up tree planting activities in challenging environments towards carbon neutrality,” Berni explained.

Planet Srl is an Italian enterprise which develops innovative products which help solve contemporary environmental issues. Its Mangrove Technology Platform is inherently passive – meaning that it works through processes of evaporation and condensation triggered by the sun’s rays. Moreover, unlike traditional approaches, its desalinisation process does not discharge brine as a waste product: instead producing edible salt as a byproduct.

“Winning the MIA Product of the Year award is an incredible honor and validation of the hard work and dedication that went into developing the Mangrove Technology Platform,” said Giulia Berni. “This recognition not only boosts our team’s morale but also increases the visibility and credibility of our innovative solution on a broader scale. The MERLIN project gave us the opportunity to showcase the MTP and interact with a diverse and dynamic audience, including environment restoration project managers, members of the freshwater ecosystem community and innovative companies across Europe.

“This exposure opens up new possibilities for partnerships and collaborations, allowing us to further refine and scale our technology,” Berni continued. “By being part of the MERLIN Marketplace and engaging with various stakeholders, we can accelerate the adoption of the MTP and contribute to the systemic, transformative change needed in our society and economy. Ultimately, winning this award helps us spread and realise our vision of promoting sustainable tree planting in arid regions while addressing water scarcity, to keep working towards carbon neutrality on a larger scale: no green without blue.”

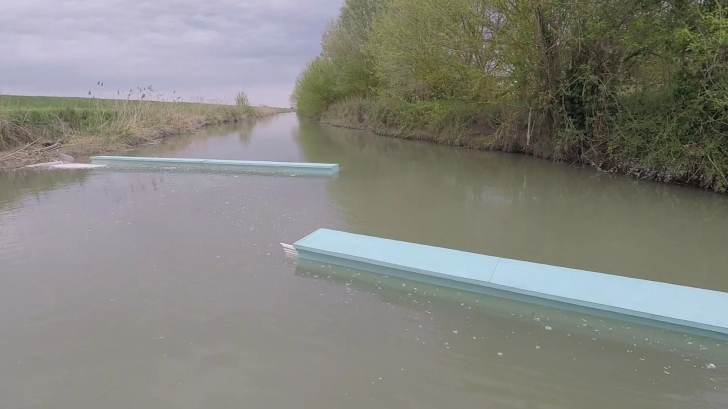

The winners of the Service of the Year are SEADS for their Blue Barriers, which are used to collect and remove plastic waste from rivers. These barriers are designed to be suspended on the river’s surface, and SEADS state that they collect close to 100% of plastic pollution in a waterway.

Between 70 and 80% of the total plastic pollution in the world’s oceans enters via rivers: totalling an estimated 10 million tonnes each year. As a result, projections suggest that by 2050 there may be more plastic in the oceans than fish, with significant negative consequences for the health of marine ecosystems. Further, it is increasingly recognised that microplastics are contaminating the food we eat and the air we breathe.

SEADS’ Blue Barriers are designed to tackle this plastic crisis. They are intended to be unobtrusive to boat traffic and to have negligible effects on wildlife living in rivers. Crucially, the Blue Barriers are economically self-sustaining, as SEADS provide sorting and transport services for the plastic waste which is collected and then transformed into recycled plastics, building materials and energy production. SEADS suggest that this means that the costs of Blue Barrier installation can be repaid in as little as three years.

“Our approach involves the development of floating barriers designed to halt plastic waste before it can enter the ocean,” said Fabio Dalmonte from SEADS. “This proactive measure is crucial because once plastic reaches the ocean, it becomes extremely challenging to collect. In fact, only 1% of ocean plastic remains on the surface, with the majority sinking to the ocean floor where it’s virtually impossible to retrieve. By intervening at the river level, where collection is efficient and targeted, we can make a significant impact.

“Our Blue Barriers are engineered to withstand seasonal flooding and can capture waste up to one metre deep in the water,” Dalmonte continued. “They are designed with exceptional flooding events in mind, ensuring safety and effectiveness. This is particularly important because much of the waste is transported during seasonal rains, not only on the river’s surface but also within the first 50cm below the water’s surface.”

Early testing of the Blue Barriers system has been carried out at the University of Florence and along the Tibor and Lamone rivers in Italy, and long-term installations are now active on the Aniene and Sarno rivers. SEADS now intend for the system to be installed more widely in countries across the world.

“Receiving this award is a tremendous honour and a testament to the dedication and teamwork of the entire SEADS team,” said Fabio Dalmonte. “We’ve put in a lot of hard work, and it’s incredibly rewarding to see our efforts recognized.

“The MIA network presents invaluable opportunities for us,” Dalmonte continued. “Establishing connections through this network is crucial for our project’s success. Whether it’s forging relationships with public administrations, attracting potential sponsors, reaching out to clients, or exploring partnerships, the MIA network can significantly amplify our reach and impact. Undoubtedly, increased visibility through this network will also be instrumental in our journey forward.”

The MERLIN Innovation Awards celebrates new and widely-applicable solutions for restoring freshwater ecosystems. The awards – organised by project partner Connectology – recognise the need for restoration projects to better engage with economic markets to support transformative ecological improvements.

You can find out about the ten shortlisted projects, and the expert jury who selected them.

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

The relationship between agriculture and the environment is a hot topic in Europe right now. In recent months farmers across the continent have been protesting to highlight a system they see as increasingly unprofitable and burdened by EU rules aimed at making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050. Farmers have organised motorway and city blockades in tractors across Greece, Germany, Portugal, Poland and France, and last week pelted the European Parliament in Brussels with eggs.

In many ways, the farmers are feeling a perfect storm of economic repercussions of the Ukraine war and COVID pandemic, coupled with the ambitious new climate directives passed down by the EU. Costs of energy, fertiliser and transport have risen across the continent following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago. However, governments across Europe have sought to manage the effects of spiralling interest rates and the cost of living crisis by stemming rising food prices.

Whilst costs are up and profits are increasingly squeezed, European farmers are also feeling the pressure of a changing climate. 2023 was the year that the extremes of the climate emergency were starkly evident across the continent, as record-breaking droughts, wildfires and irrigation restrictions became commonplace across Southern Europe.

Amidst the challenges of producing food in a changing climate, farmers have to work within the rules set by the EU, which attempt to shift our agricultural system towards a more biodiversity-friendly and climate-neutral state. The European farming sector accounts for around 11% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, and as such will require significant reorganisation to achieve the European Green Deal goal of making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050.

Crucially, whilst the negative effects of intensive agriculture on European biodiversity are well documented, farmers argue that the targets in the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy and Nature Restoration Law to reduce their environmental impacts are overly punitive in the current economic climate. These targets include cutting fertiliser use by 20% and halving pesticide use by 2030, alongside allocating more land to non-agricultural use and doubling organic production.

In the wake of this wave of farmers’ protests the European Commission this week announced it was cancelling plans to half pesticide use in the EU by 2030. And last week, the bloc also announced delays to regulations on set-aside land intended to boost soil health and biodiversity in farmland across the continent.

This leaves European environmentalists in a tricky situation. Clearly, European farmers are increasingly squeezed economically. However, it is increasingly agreed that there is an urgent need for transformative actions to help preserve and restore European ecosystems. A key element of this work is to make agriculture more sustainable, both economically and environmentally.

As such, there is a pressing need to understand how different forms of agricultural practices affect European ecosystems, and whether the most harmful approaches can be transformed in ways that can support both nature and farmers’ livelihoods.

A new study explores how the impacts of different agricultural approaches across Europe affect the ecological health of rivers and streams across the continent. A research team led by Dr. Christian Schürings from UDE in Germany analysed data on agricultural land use across 27 European countries. Writing in Water Research, the researchers then linked this analysis to data on the ecological status of flowing waters across the continent, from small streams to huge rivers like the Ruhr and Rhine.

They found that the health of river and stream ecosystems in Europe is strongly influenced by the type of agriculture that is practiced in the landscapes which they flow through.

“Intensive farming has the greatest impact,” says Dr. Schürings. “This includes irrigated agriculture, as practiced in Southern Europe, for example in Spain, Portugal and Italy, and the intensive use of pesticides and fertilisers on land in Western Europe. This is particularly common in France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and the U.K.”

In many ways, this is not a surprising result. Aquatic scientists have long highlighted the negative impacts of intensive agriculture on our freshwaters, particularly due to pesticide and fertilisers polluting waterways, floodplains being lost to farmland, rivers straightened and abstracted for irrigation. The new study offers is a valuable map of where such agricultural pressure on freshwaters are highest across Europe – particularly clustered in Southern and Western Europe.

On the other hand, the study shows that less-intensive and organic forms of farming have little-to-no negative impacts on the rivers and streams which they border. Small-scale agriculture, which involves less chemical inputs and often occurs over a mosaic of habitats including hedgerows and fallow land, is shown by the authors to be a more river-friendly alternative to existing intensive practices.

“Our results underline that the transition to more sustainable forms of agriculture, such as organic farming, is beneficial for rivers,” says Dr. Schürings. However, the key question remains, how can this transition remain economically viable for farmers?

Decades of agricultural management under the Common Agricultural Policy have encouraged farmers to pursue economies of scale, where profits are boosted by bigger and more efficient farm holdings. Amidst the turmoil of farmers’ protests, how can the need to protect and restore freshwater life be upheld in decisions over how to manage European agriculture?

For co-author Dr. Sebastian Birk, the answer lies in the benefits that healthy, functioning ecosystems can provide to humans. As explored in the MERLIN project, such nature-based solutions can offer a system in which farmers can be economically rewarded for shifting their practices to benefit the environment.

In river catchments, this can include the restoration of floodplains to naturally-buffer flood waters, or the creation of wildflower meadows to boost pollinating insect populations. Such approaches could offer farmers incentives to reduce their environmental impacts, whilst benefiting economically from the healthy functioning of the ecosystems on which they rely.

For Dr. Birk, this means that, “water protection and agriculture can go hand in hand. The EU should support this through a restructuring of agricultural subsidies, so that the environmental services provided by agriculture are more strongly rewarded.”

///

MERLIN Podcast EP.6 – Water, climate and farming: making space for stream restoration in Portugal

In this episode of the MERLIN Podcast we explore the issues around stream restoration in the Sorraia catchment in Central Portugal.

Restoration of the Sorraia river needs to be able to navigate the needs of intensive agriculture in a landscape increasingly affected by the climate crisis. Walking along the banks of the river, we meet a range of freshwater scientists, activists, farmers and policy experts to understand the big issues in the Sorraia catchment, and the ways in which restoration is increasingly making space for this river in the landscape.

We also hear about how work on the Sorraia relates to wider debates over farming, freshwater restoration and the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Top posts of 2023

In these early days of the new year, we continue our annual tradition of looking back at the top posts of the previous year. 2023 was a year when the realities of the climate emergency and biodiversity crisis really became apparent, as extreme weather and dire warnings about ecosystem declines made regular front page news across Europe.

Throughout the year, we followed the complex and hotly-debated route taken by the ambitious EU Nature Restoration Law towards adoption. If ratified – as it looks as will happen early this year – the law commits European countries to rapid and signficant ecosystem restoration activities on land, in freshwater, and at sea.

We also followed the rising prominence of nature-based solutions as a key focus of contemporary environmental management and policy. These approaches, which foreground the potential of natural processes to generate ecological, social and economic benefits, are rapidly growing in popularity, and we will continue to explore the big questions over their ongoing adoption.

And finally, 2023 was the year when our work on the MERLIN podcast really took off, with new episodes covering peatland restoration, nature-based solutions, economic thinking and much more. If you haven’t already tuned in and subscribed to the podcast, then please consider doing so: 2024 is set to be an exciting year.

And on that note, we want to say a big thank you to you, our readers and listeners, for your eyes and ears through 2023. We really appreciate you, and are always happy to hear your thoughts, whether by email or on our social media platforms.

///

Ecosystem restoration and nature-based solutions: how do they differ and why does it matter? (January)

Awareness of the need to restore Earth’s ecosystems has become increasingly mainstreamed in recent years. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration began in 2021, marking the start of increased efforts to halt the degradation of global ecosystems, and restore them to mitigate the effects of climate change and stop the collapse of biodiversity.

More recently still, the concept of nature-based solutions has entered the global environmental conversation. Nature-based solutions aim to manage natural processes to bring benefits to both people and ecosystems. For example, planting native forests in watersheds can help naturally filter water supplies, and reintroducing beavers can create the floodplain environments which buffer flooding.

As a result, the terms ecosystem restoration and nature-based solutions are often used interchangeably. And, of course, there is significant overlap between them: nature-based solutions are an increasingly central part of many restoration projects globally. But given the rapid growth of both approaches, it is useful to ask: how do they differ, and why does it matter? (read more)

///

We all need freshwater biodiversity (February)

We are in a crucial ‘window’ of time to protect and restore global freshwater biodiversity, according to a major new journal article. The authors – a group of scientists from across the world – write that there is growing public and political recognition of the need to ‘mainstream’ biodiversity conservation across all areas of everyday life.

Writing in the WIRES Water journal, the authors highlight the vital roles that freshwater biodiversity plays in supporting human lives: from food and materials; to cultural and recreation; and climate regulation to water purification. As a result, conserving and restoring freshwater habitats offers a path towards achieving what the UN term the ‘future we want’: a more sustainable future for people and nature. (read more)

///

MERLIN Innovation Awards celebrates innovative approaches to freshwater restoration at 2023 ceremony (February)

Last week, the EU MERLIN project announced the winners of its annual Innovation Awards, which highlight cutting-edge solutions for modern freshwater restoration. Entries from organisations across the world were assessed by an expert panel, and shortlists for the two categories – Service of the Year and Product of the Year – were drawn up. Two winners were announced at a busy and energetic ceremony on Wednesday.

The winners of the Service of the Year are Plastic Fischer, a social enterprise which collects and manages river plastic to prevent it entering the oceans. The organisation was founded in 2019 in response to its founders witnessing the continuous stream of plastic, styrofoam and other waste that floated down the Mekong River in Vietnam, towards the ocean. The idea was formed to build a waterwheel that automatically collects plastic waste from rivers, and lifts it to shore to be disposed of.

The winners of the Product of the Year are Ecocean, a French company which specialises in developing new technologies to support the sustainable use of aquatic environments. One of the organisation’s flagship innovations is FLOLIZ – a series of artificial floating rafts which help boost biodiversity, both above and below the water’s surface. (read more)

///

MERLIN Podcast Episode 3 – Restoring Europe’s peatlands and wetlands (June)

Peatlands and wetlands are vital landscapes. They store carbon and so help mitigate the harmful effects of climate change, they help buffer floodwaters and naturally filter drinking water, and they are often rich habitats for biodiversity. But peatlands and wetlands have been widely drained, altered and lost across Europe as a result of human actions.

This episode explores how peatlands and wetlands across the continent are being restored through a series of ambitious projects supported by the MERLIN project. Podcast host Rob St John meets a range of restoration scientists and managers implementing so-called ‘nature-based solutions‘ at their sites across Europe. Their schemes include beaver reintroduction, peatland ‘rewetting’ and wet woodland restoration. (read more)

///

How nature-based solutions can benefit freshwater biodiversity (June)

One key element of nature-based solutions is that they are designed to offer clear economic and social rationales for the value of protecting and restoring natural environments. Advocates of nature-based solutions suggest that this helps strengthen arguments over the value of mainstreaming environmental restoration to benefit all our lives.

In this context, a newly-published open-access paper explores whether nature-based solutions can make meaningful contributions to tackling the freshwater biodiversity crisis. Writing in PLOS Water, Dr. Charles van Rees and colleagues highlight how nature-based solutions can offer ‘win-wins’ for nature and society, but emphasise that clear links must be made between their use and priorities for freshwater conservation. (read more)

///

Large river restoration under the spotlight along the banks of the Tisza River (July)

The Tisza River flows nearly a thousand kilometres from its source in Ukraine through Hungary to meet the Danube in Serbia. In places, the Tisza supports rich and varied biodiversity, particularly bird species, mayflies and floodplain meadows. However, the Tisza’s course and floodplains have been altered for well over a century through dam construction, dredging and channel straightening.

The EU-funded MERLIN project is supporting the restoration of the Tisza river at two sites close to the village of Nagykörű in Hungary. Floodplains surrounding the river – which have been drained and cut off from the river to support intensive arable farming – are being ‘rewetted’. This process is intended to increase water retention in the floodplains, which will help buffer floodwaters and create valuable biodiversity habitat. In turn, the plan is for the rewetted Tisza floodplains to support more sustainable farming practices. (read more)

///

Biodiversity recovery in European rivers has stagnated since 2010 (August)

Biodiversity in European rivers increased between 1968 and 2010 due to improved water quality following decades of environmental pollution, according to a new study. However, this trend of biodiversity recovery has stalled since 2010.

Writing in the journal Nature, an international team of researchers attribute this finding to the limited potential of existing measures to continue to drive water quality improvements. This is due to the growing impacts of complex stressors such as climate change, which need to be urgently tackled with ambitious new environmental restoration and policy strategies, the authors argue. (read more)

///

Water, climate and farming: making space for stream restoration in Portugal (October)

Last week, researchers from the MERLIN project working on the restoration of small streams across Europe met in Lisbon, Portugal to discuss progress and visit case study sites. Following exchanges at the University of Lisbon, the group visited restoration projects in the Sorraia and Ervidel catchments. With the MERLIN project at the half-way point, discussions centred on how to measure the impacts of restoration projects, and how to gain support from policy makers and financiers to upscale their use across Europe.

Working with the concept of nature-based solutions, the indicators of restoration impact used by MERLIN are not only environmental, but also social and economic. This means that researchers are not only monitoring how restoration is affecting factors like biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions at their sites, but also how it impacts things like green job creation and private finance mobilisation. The idea is to help build a convincing case for upscaling freshwater restoration across Europe by showing that it can benefit people as well as nature. (read more)

///

The High Cost of Cheap Water: annual economic value of global freshwater ecosystems estimated at $58 trillion (October)

Freshwater is “the world’s most precious and exploited resource” but has always been significantly undervalued in global economies, leading to widespread environmental costs, according to a major new WWF report published this week.

The report estimates that the annual economic value of water and freshwater ecosystems globally is $58 trillion – a figure equivalent to 60% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This startling figure was calculated by estimating the financial value that rivers, streams, lakes, reservoirs and wetlands generate to human societies. Direct economic benefits including water for household drinking, cooking and cleaning, irrigation for agriculture, and to supply industries was calculated at $7.5 trillion each year.

However, the indirect – and often invisible – benefits freshwaters bring to human societies are significantly higher. The report estimates that such indirect values – including purifying water, increasing soil health, storing carbon and buffering communities from floods and droughts – are around $50 trillion annually. (read more)

///

Working with nature to shape a healthier future for Europe’s rivers (November)

The MERLIN project recently released a new infographic showing the value of nature-based solutions to help restore Europe’s rivers. Its ‘Vision for Europe’s rivers’ illustrates how five different kinds of management measures can help produce a range of valuable benefits for people and nature.

The infographic shows how nature-based solutions can be deployed all the way along a river catchment. In the mountainous headwaters, it illustrates how ‘rewiggling’ rivers across their natural floodplains can help boost biodiversity and provide valuable spaces for recreation. Further downstream, it shows how measures such as ‘green cities’ and wetland restoration can help buffer flood and drought risks, and help boost carbon storage in the landscape. (read more)

///

Promises and pitfalls of the EU Nature Restoration Law (December)

Last month, the ambitious EU Nature Restoration Law moved a step closed to adoption following a provisional agreement between policy makers. Originally proposed in June 2022, the law obligates European countries to restore at least 20% of their land and seas by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

Earlier this month, researchers from four major EU environmental restoration projects published an article in Science assessing the promises and pitfalls of the proposed law, which is expected to be approved in a final vote early in 2024.

It is widely acknowledged that the magnitude of the biodiversity crisis and climate emergency requires rapid and ambitious attempts to conserve and restore Europe’s ecosystems. Research is increasingly showing how such measures aren’t only good for nature, but for people too: as healthy, resilient ecosystems bring significant benefits to our everyday lives in society.

Writing in Science, the authors of the new paper highlight that the Nature Restoration Law acknowledges the failure of existing EU policy and legislation to halt biodiversity losses, and the pressing need for new policies which can help Europe meet the targets of international environmental agreements. (read more)

///

You can read all our 2023 articles here – happy 2024!

Promises and pitfalls of the EU Nature Restoration Law

Last month, the ambitious EU Nature Restoration Law moved a step closed to adoption following a provisional agreement between policy makers. Originally proposed in June 2022, the law obligates European countries to restore at least 20% of their land and seas by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

Earlier this month, researchers from four major EU environmental restoration projects published an article in Science assessing the promises and pitfalls of the proposed law, which is expected to be approved in a final vote early in 2024.

It is widely acknowledged that the magnitude of the biodiversity crisis and climate emergency requires rapid and ambitious attempts to conserve and restore Europe’s ecosystems. Research is increasingly showing how such measures aren’t only good for nature, but for people too: as healthy, resilient ecosystems bring significant benefits to our everyday lives in society.

Writing in Science, the authors of the new paper highlight that the Nature Restoration Law acknowledges the failure of existing EU policy and legislation to halt biodiversity losses, and the pressing need for new policies which can help Europe meet the targets of international environmental agreements.

The authors outline that the promise of the Nature Restoration Law meeting its aims will be strongly shaped by how it coheres with existing European legislation and policies. This ‘policy coherence’ includes supporting the goals of existing environmental policies – such as the Habitats Directive and Water Framework Directive – and better integrating environmental concerns into other policy areas.

One key attribute of the Nature Restoration Law is its ambitious targets, timelines and implementation steps towards 2030, 2040 and 2050. However, the authors of the new paper highlight that the success of the law hinges on prompt action, and the rapid deployment of effective management measures to allow nature to recover.

“The NRL avoids several pitfalls that often obstruct the implementation of European policies and regulations, showing that the Commission learned from past experiences,” said lead author Daniel Hering from the MERLIN project. “The regulation sets ambitious targets and timelines, and implementation steps are clearly laid out. It also saves time as it does not need to be transposed into national law.”

As Prof. Hering cites, the Nature Restoration Law is designed to be quickly adopted by European countries. One key strategy for this adoption is through National Restoration Plans, which obligate member states to prepare restoration plans to achieve the targets laid down in the law.

The authors highlight the vast potential of the Nature Restoration Law to boost the implementation of existing European environmental directives and policies. They state that the law is “broad but targets specific ecosystem types with tailor-made approaches… [which] may therefore have impacts beyond the targeted ecosystem.” For example, the restoration of agricultural land can benefit rivers and lakes. In other words, the large-scale restoration of European ecosystems could spark a domino effect of nature recovery across different landscapes.

Accordingly, the authors suggest that whilst the Nature Restoration Law may appear ‘conservative’ in its focus on the protection and restoration of habitats – rather than more contemporary holistic and adaptive approaches – it holds considerable potential to catalyse such large-scale nature recovery. Moreover, the authors state that whilst contemporary ecosystem-based approaches and nature-based solutions are only briefly mentioned in the law, it holds significant capacity to help support the widespread social benefits they can catalyse through restoration.

The authors suggest that the lofty ambition of the Nature Restoration Law and the clear targets and timelines towards achieving its goals it contains offer explanations for its slow and contested path towards adoption. Lobby groups – particularly from agricultural organisations – have argued for its provisions to be watered-down throughout the process.

Implementing the Nature Restoration Law across agricultural landscapes is thus a key challenge to overcome. “Intensive agriculture is still a key driver for biodiversity loss in Europe”, said co-author Guy Pe’er from the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research (UFZ). “But targets for agriculture and nature restoration could be coordinated, with opportunities for both.”

More broadly, the authors identify that a recurring problem with the implementation of European environmental policies is that gap between targets and effective implementation options. They highlight that the Nature Restoration Law must be implemented by European countries following strict procedures and resilient funding structures in order to give it the best chance of success.

However, there is significant work for European countries to do on bringing groups of land and water owners, managers and funders together to achieve these goals together. “While targets are precisely defined and binding, the steps to achieve them need to be decided by individual European countries and most of them are voluntary” said co-author Josef Settele from the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research (UFZ).

The authors conclude that the ambition and rapid timescale of the Nature Restoration Law is to be welcomed, but its success will hinge on how well it is translated into action. This process requires strong policy, which supports existing European legislation, and stable long-term funding streams to allow for the gradual recovery of nature across the continent.

They write: “Given the urgency of global crises, Europe cannot afford to delay; the opportunity to install and implement an ambitious law, and the opportunity to show global leadership, should not be missed.”

///

The authorship of the paper includes the coordinators of the projects MERLIN, WaterLANDS, SUPERB and REST-COAST that are all funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme under the topic “Restoring biodiversity and ecosystem services” (LC-GD-7-1-2020).

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Climate deal struck at COP28 as research shows nearly a quarter of global freshwater fish at risk of extinction

A new climate deal was struck yesterday at COP28 in Dubai, which includes a clear imperative for global countries to transition away from fossil fuel use in order to acheive net zero emissions by 2050.

Produced through extensive negotiations between global nations, the deal emphasises “the need for deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions” in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

After nearly 30 years of COP meetings, this is the first time a deal has explicitly called for the transition away from global fossil fuel use. The deal – a first ‘global stocktake’ following the Paris Agreement at the 2015 COP21 – calls on countries to contribute to a global tripling of renewable energy capacity and doubling of energy efficiency improvements by 2030.

However, many climate campaigners believe the deal does not reflect the scale and urgency of fossil fuel reductions required to keep the planet within safe climatic limits in the future. The language of ‘transition away’ is weaker than that of a definitive ‘phasing out’, particularly in a world where fossil fuel producers are planning major expansions in production.

Moreover, the deal cites the need to expand the use of carbon capture and utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies. This is seen by climate campaigners as a concession to lobbyists from fossil fuel states such as Saudi Arabia, who see carbon capture and storage as a way of continuing their lucrative petrochemical extraction businesses.

The importance of mitigating the scale of climate change and its impacts on global biodiversity and ecosystems is repeatedly flagged in the deal. The value of ecosystem-based adaptions and nature-based solutions in helping build climate change resilience is highlighted in the deal, but for some experts, this focus could be stronger.

‘A significant development is the inclusion of an explicit reference to the Kunming Biodiversity Global Biodiversity Framework agreed at the UN Convention of Biological Diversity,” said Professor Nathalie Seddon from the University of Oxford. “However, there is a lack of language on the importance of guidelines for high-integrity nature-based solutions, that ensure local benefits for people and biodiversity as cornerstones of resilience in a warming world.”

Limiting climate change is vital for safeguarding the future of freshwater biodiversity and ecosystems, as the publication of the new IUCN Red List starkly demonstrates. Published earlier this week, the new Red List assessment shows that nearly a quarter of the world’s freshwater fish are at risk of extinction due to climate change, pollution and overfishing.

The report shows that at least 17% of all threatened freshwater fish species are impacted by climate change, including decreasing water levels, rising sea levels causing seawater to move up rivers, and shifting seasons.

“It is shocking that one quarter of all freshwater fish are now threatened with extinction and that climate change is now recognised as a significant contributing factor to their extinction risk,” said Dr Barney Long, Re:wild’s Senior Director of Conservation Strategies, who contributed to the research. “It is critical that we better safeguard our freshwater systems as they are not only home to precious and irreplaceable wildlife, but also provide humans with so many services that only the natural world can.”

One headline story from the report is that the Atlantic salmon – previously common across northern Europe and North America and classified as ‘least concern’ – is now at ‘near threatened’ by extinction. Research for the Red List shows that global populations of Atlantic salmon fell by 23% between 2006 and 2020. This is due to a complex mix of threats to the fish – including climate change, overfishing, pollution, dam production and aquaculture – at all life stages, and over vast geographical areas.

“Climate change is menacing the diversity of life our planet harbours, and undermining nature’s capacity to meet basic human needs,” said Dr Grethel Aguilar, IUCN Director General. “This IUCN Red List update highlights the strong links between the climate and biodiversity crises, which must be tackled jointly. Species declines are an example of the havoc being wreaked by climate change, which we have the power to stop with urgent, ambitious action to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.”

A major new initiative to help safeguard freshwater ecosystems from the threat of climate change received a boost this week, as 37 countries joined the Freshwater Challenge. The scheme aims to ensure that 300,000km of degraded rivers and 350 million hectares of degraded wetlands are committed to restoration by 2030, whilst other global freshwater ecosystems are protected.

The new countries – from Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America, and the Pacific – were announced at the COP28 conference, joining the six countries that launched the initiative at the UN 2023 Water Conference in New York – Colombia, DR Congo, Ecuador, Gabon, Mexico and Zambia.

“With the climate crisis fuelling ever more extreme floods, storms, wildfires and droughts, we urgently need to invest in protecting and restoring our rivers, lakes and wetlands,” said HE Razan Al Mubarak, UN Climate Change High-Level Champion for COP28. “They are the best natural protection for our societies and economies as well as major carbon stores. Rising to the Freshwater Challenge is key to tackling climate change, but it is also essential to pave the way to a net-zero, nature-positive and resilient future for all.”

“Healthy rivers, lakes and wetlands are our best buffer and insurance against the worsening impacts of climate change,” added Stuart Orr, WWF Global Freshwater Lead. “Investing in their protection and restoration will produce the most important returns: strengthening climate adaptation and reducing disaster risk as well as increasing water and food security, and reversing the catastrophic decline in freshwater biodiversity. But we need to find new pathways to address this urgently.”