Structuring the biodiversity informatics community: the recent Horizons 2013 conference

In beautiful September weather, the European biodiversity informatics community, met in Rome for a three day conference to assess the state of the art and develop a strategy to engage constructively with Horizon 2020. The BIH 2013 was a significant step towards realising the Commission’s wish that consortia formation becomes more collaborative and less competitive.

BioFresh contributed to discussions in a number of ways: Aaike De Wever chaired a session titled “the who and the where”, each break Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber demonstrated our new information platform and Paul Jepson talked on BioFresh experiences with data mobilisation and presented a schematic to aid thinking on informatics futures.

Dr Schmidt-Kloiber demonstrating the BioFresh Platform at BIH2013

The conference concluded by stating the goal of biodiversity informatics as “delivering predictive modelling for biodiversity”. It was agreed that the community must move beyond digitizing things and start asking specific and applied questions. In the shorter term, the conference agreed the need to improve clarity of vision with greater focus on end-goals, to develop good, simple tools with syntactic operability, to build the identify of the biodiversity informatics community and to strengthen links. Summarised with the words: integration, co-operation, promotion.

The need to strengthen links referred to links with people, other disciplines and sectors as well as machines. Drawing on BioFresh experiences, we argued that data mobilisation must not be seen solely as a technological and resourcing challenge but also as a process with complex science sociology and cultural dimensions. We suggested a more personalised approach to building relations with data holders drawing on insights from fund-raising and lobbying colleagues. Paul Jepson also flagged how speakers were referring to policy in very general terms and commented that links in this area would be enhanced by engaging academics with disciplinary expertise in environmental governance, policy and politics. He also argued for a more expansive notion of informatics and one that more explicitly engaged with developments in automated sensing and mobile (citizen science) technologies. Click here to view our powerpoint presentation.

(c) P. Jepson Extended Vision of Biodiversity Informatics. Sept 2013

The conference organisers, Dave Roberts and Alex Hardisty have set up a mail list for the their white paper on biodiversity informatics published earlier this year which interested parties can ask to join. In addition that individuals can register their research group on the H2020 webpage if they are interested in becoming involved in consortia responding to future EU research and networking calls. A fuller summary of the conference will be published on this site in due course.

Here are some key papers and reports

Hardisty, A., Roberts, D. & The Biodiversity Informatics Community. (2013). A decadal view of biodiversity informatics: challenges and priorities. BMC Ecology 13, 16

Hobern, D., Apostolico, A., Arnaud, E., Bello, J. C., Canhos, D., Dubois, G., Field, D., García, E. A., Hardisty, A., et al. (2013). Global Biodiversity Informatics Outlook: Delivering Biodiversity Knowledge in the Information Age. GBIF Secretariat.

European Commission. (2013). Towards a Roadmap for Biodiversity and Ecosystem research in Europe. Workshop, Brussels.

Hardisty, A. (2012). Comparison of Technical Basis of Biodiversity e-Infrastructures. , Coordination of Research e-Infrastructures Activities Toward an International Virtual Environment for Biodiversity. Cardiff University.

Purves, D., Scharlemann, J. P. W., Harfoot, M., Newbold, T., Tittensor, D. P., Hutton, J. & Emmott, S. (2013). Ecosystems: Time to model all life on Earth. Nature 493, 295–297. doi:10.1038/493295a

Water funds: an “ideal” PES project – or better?

As payments for ecosystem services (PES) gain momentum, rules of “best practice” are also emerging. But how do these “ideals” for PES projects work on the ground, and what happens if you don’t follow them exactly? Rebecca Goldman-Benner and her colleagues at The Nature Conservancy ask precisely such questions in their 2012 Oryx paper,”Water funds and payments for ecosystem services: practice learns from theory and theory can learn from practice.” The group looks at South American water funds as examples to measure a theoretical PES project against the reality, and find that a little flexibility may not be a bad thing.

García Moreno street in the historic centre of Quito, Ecuador. The Andean city initiated South America’s first major water fund in 2000. Its Fondo para la Protección del Agua (FONAG) has become a model for the entire region. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Author: Cayambe.

The Latin American Water Funds Partnership, set up by The Nature Conservancy in partnership with FEMSA Foundation, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), is launching 45 funds in various stages of development across the Caribbean and Latin America. The oldest, Quito’s Fondo para la Protección del Agua (FONAG), dates back to 2000. Although the structure has started to vary as the programs expand, the original projects in Ecuador and Colombia typically rely on an independently-governed trust fund. Downstream water users such as cities, utilities, and industries pay into the fund, which then pays upstream landowners to use their land in a more eco-friendly way. Investments focus on maintaining a clean, reliable supply of water throughout the year, as well as protecting ecosystems around the watershed and securing alternative livelihoods for upstream residents. A trust fund structure has been suggested for other kinds of PES projects too – for example, as a model for the wildlife media (for more information, see the previous BioFresh post discussing the current Oryx forum on PES and the wildlife media).

The Artisana reserve is part of the watershed for Quito. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Author: Author: Stefan Weigel.

Broadly speaking, this falls under the spirit of payments for ecosystem services. PES are supposed to convince landowners to manage their land in a way that promotes conservation and benefits others – for example, reducing fertilizer use in a sensitive watershed protects an ecosystem service (clean water supply) for everyone who uses that water. But this relies on two rules. First, the payments have to make the difference – they have to convince land managers to act in way that they wouldn’t otherwise. This is known as additionality. Secondly, the payments can only continue if the landowners in question provide the ecosystem service and then continue to protect it. This is called conditionality; in effect, making sure service “buyers” aren’t paying something for nothing.

Aerial view of the River Pirai in Bolivia, with Santa Cruz in the background. The Fundación Natura Bolivia has collaborated with departmental and municipal government to establish the water fund FONACRUZ. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Author: Sam Beebe.

In practice, water funds deviate somewhat from both of those rules. Additionality is very difficult to measure exactly, since it involves both putting a fixed price on a piece of land’s watershed value and figuring out what would have happened in a pretend future where the landowners weren’t paid to conserve. Also, a trust fund model means payments are usually made from the accumulated interest – this violates the conditionality rule, since you can’t just withdraw your money from the fund if you think the payments aren’t getting upstream landowners to conserve the watershed.

But Goldman-Benner and her colleagues claim that these departures from the strict PES definition may allow water funds to work better in the long term. Violating conditionality by using the interest from a trust fund rather than direct contributions keeps a sustainable source of financing for the project and protects the fund from political instability. It also gives the service users a reason to stay involved long-term. And targeting people who are more likely to conserve their land anyway (against the idea of additionality) may take advantage of “social diffusion” – the idea that if a small set of a population (sometimes as little as 15%) take up an initiative, then it may act to influence everyone else to do the same.

As more and more institutions move forward with payments for ecosystem services, from the World Bank to the UK government to NGOs like WWF, the tendency may be for an ever-more-standardized definition of PES. Goldman-Benner and her colleagues say that staying flexible about what constitutes a PES project allows for creative approaches that fit local realities, not just international ideals. However, Goldman-Benner argues that it is also critical to measure true return on investment from the water funds. “We need to not just show we are paying for keeping cows out of waterways, but that by doing so we are providing water with less sediment at a scale that matters,” she says.

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Freshwater Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Goldman-Benner, R.L. et al., 2012. Water funds and payments for ecosystem services: practice learns from theory and theory can learn from practice. Oryx, 46(01), pp.55–63. Available at: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0030605311001050.

Cabinet of Curiosities: the walking catfish (Clarias batrachus)

Our new entry to the BioFresh Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities is the remarkably destructive walking catfish.

It breathes air, eats practically anything, and “walks” using its pectoral fins, wriggling along as it searches for water. It’s the walking catfish, and its bizarre lifestyle makes it both fascinating and disastrous for freshwater ecosystems.

A native to southeastern Asia, the catfish has been introduced around the globe, including the UK and the US, where in Florida it has been recorded coming up from sewers in schools of 30 fish and going for a waddle down the street. According to George Monbiot, who’s included the fish in his book Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Edges of Rewilding, it eats “anything that moves,” and it’s especially dangerous because it can walk to isolated pools that other invaders can’t reach. It poses a particular threat to fish farms, eating its way through millions in valuable stock. The catfish spread rapidly through Florida in the 1960s and 70s, due in part to releases and escapes from aquariums, and it is now banned by several countries, although it can sometimes still be found in pet stores. Potential owners are warned to keep the walking catfish in a secure aquarium, so that it doesn’t just squirm away. Check it out among the other amazing creatures in Biofresh’s Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities!

Perspective: Should the wildlife media pay for ecosystem services?

![By Kloer Phil, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://freshwaterblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/film_tv_crew_in_wildlife_show.jpg?w=728)

By Kloer Phil, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The logic of Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) proposes that companies that utilize ecosystem services in the production of their goods (termed service buyers) should pay a fee to those who manage or maintain the relevant aspects of the ecosystem (services providers). The Catskills Watershed is a famous example of PES in action.

In December 2012 some colleagues and I published a thought-piece in Science asking whether the logic of PES could be extended to media corporations who produce natural history content and are therefore users of ecosystem services. Our aim was to prompt discussion on the boundaries of PES approaches: in what cases are they appropriate/inappropriate?

To this end we outlined a possible PES scheme for media corporations that blends certification and a trust fund model. In brief, the idea is that a consortium (maybe of NGOs) would established a certification scheme for natural history content whereby certified broadcasters would pay a royalty into a trust fund (similar to that used in water funds, see Goldman-Benner et al 2012) and include an interactive facility whereby viewers could find out about, and donate to, relevant conservation projects. The trust fund would be independently administered and finance conservation initiatives based on transparent priorities.

Today Oryx has published a forum which takes up this discussion. Sven Wunder (who produced the most widely accepted definition of PES – see Wunder 2007) and Doug Sheil argue against the notion. In a nutshell they argue a) that this level of innovation with the PES concept would undermine its utility and b) that the wildlife media contributes to conservation in many and varied ways and increasing the production fees of natural history films would be counter-productive.

For me debating the question of whether the wildlife media should embrace PES also helps interrogate and unpack the concept of ‘cultural’ ecosystem services and in particular whether they can be valued in economic or market terms, Our discussion on the wildlife media raises the interesting point that cultural ecosystem services are in fact co-produced by companies, publics and nature. As a result the distinction between service buyer and service provider is blurred and transaction value likely impossible to ascertain

For me debating the question of whether the wildlife media should embrace PES also helps interrogate and unpack the concept of ‘cultural’ ecosystem services and in particular whether they can be valued in economic or market terms, Our discussion on the wildlife media raises the interesting point that cultural ecosystem services are in fact co-produced by companies, publics and nature. As a result the distinction between service buyer and service provider is blurred and transaction value likely impossible to ascertain

In her video post Professor Strang commented that ‘the concept of cultural ecosystem services misses the point of culture’ and I tend to agree.

Paul Jepson

Forum Articles

To facilitate this discussion the journal Oryx and Cambridge University Press have kindly made the forum articles open access for 3 weeks. Our Science forum article can be accessed via my university web-page

Jepson, P., Jennings, S., Jones, K.E., & T. Hodgetts (2012) Entertainment Value: should the media pay for conservation? Science, 334(6061): 1351-135

Wunder, S. & D. Sheil (2013) On taxing wildlife films and exposure to nature

Jepson, P & S. Jennings (2013) Should the wildlife media pay for conservation? A Response to Wunder & Sheil

Wunder, S. & D. Sheil (2013) Wildlife film fees: a reply to Jepson & Jennings

Other papers

Goldman-Benner et al 2012 Water Funds and Payments for Ecosystem services: practice learns from theory and theory learns from practice Oryx 46:55.

Wunder, S (2007) The efficiency of payments for ecosystem servcies in tropical conservation. Conservation Biology 21, 48-58

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Freshwater Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

This quest post by Kevin Smith of the IUCN Global Species Programme responds to Susanne Schmitt’s request for information to strengthen the freshwater arguments of WWF’s Campaign to keep oil exploration out of the Virunga World Heritage Site.

This quest post by Kevin Smith of the IUCN Global Species Programme responds to Susanne Schmitt’s request for information to strengthen the freshwater arguments of WWF’s Campaign to keep oil exploration out of the Virunga World Heritage Site.

Dr. Susanne Schmitt recently wrote for this blog, describing how WWF are campaigning for SOCO International, who own oil exploration licence for ‘Block V’ which covers a large part of the Virunga National Park and Lake Edward, to stay outside the park boundaries. WWF have highlighted the high biodiversity value of the lake, and others in the region, but it is often hard to find a central data resource with information on the biodiversity present (other than birds and mammals) – as would be needed in support of any Environmental Impact Assessment conducted.

IUCN, through its work on freshwater biodiversity assessments in Africa (including all species of fishes, molluscs, dragonflies, and crabs), has however, made large amounts of data freely available to help inform decision making processes such as these. Our data can be accessed in a number of ways, from the online ESRI powered ‘Freshwater Biodiversity Browser’ (Figure 1) which lets the user query any sub-catchment in Africa to identify which species of fish, mollusc, dragonfly, crab or aquatic plant is found within it, or with a smart phone using the ESRI Arc GIS app* (Figure 2). The app is the same as the desktop version but allows field workers to use their location (through gps on the smart phone) to query what freshwater biodiversity may be in the sub-catchment they are standing in. The species data all links back to the IUCN Red List, where you can find out more information on the conservation status of the species, and download the species distribution data.

Figure 1. IUCN Freshwater Biodiversity Browser (African freshwater species so far), allows the user to identify what species (with information on Red List status, utilisation, threats etc) are in every sub-catchment across Africa.

Figure 2. Freshwater Biodiversity Browser, allows the user to identify what species are in the sub-catchment they are located in the field.

Of the approximately 80 fish taxa in Lake Edward and the closely connected Lake George, the majority are from the family Cichlidae (including haplochromines) most of which are found nowhere else in the world (Snoeks 2000) and so are effectively “irreplaceable”. Using data from the IUCN Red List assessments along with their range information the distribution of threatened species within the immediate Lake Edward and George basin can be shown (Figure 3). Currently there are no globally threatened fish species within Lake Edward, or within the Block V oil concession area, (at least at the time of the assessments in 2006!). The threatened species of the basin are found in the Ruwenzori river systems or within Lake George and the Kazinga Channel. These species are primarily threatened by pollution from mining activities. However, the high levels of endemicity within Lake Edward cannot be ignored (Figure 2). The species flock of Lake Edward may not yet be threatened, but any impacts in the future to Lake Edward, or its upstream catchment (covering almost the entire ‘Block V’ area) would more than likely impact those endemic (irreplaceable) species possibly causing them to classified as threatened or even extinct.

Figure 3. The number of threatened freshwater fish species in the immediate Lakes Edward and George basin

Figure 4. The number of freshwater fish species endemic to the immediate Lakes Edward and George basin

The impacts to freshwater biodiversity itself, although very important, is not the only aspect that need to be considered when assessing the likely impacts of development upon freshwater systems. The links between biodiversity and ecosystem services need to be identified and considered, even if this is only possible for the most the obvious services (provisioning e.g. food). There are many other fish species within Lake Edward and its basin that are not endemic but play a crucial role in human livelihoods and food security. A recent IUCN study on the values of freshwater fish of Africa’s Albertine Rift (which uses the Red List assessments), found that 60% of fish species within the wider Albertine Rift lakes are important for human use primarily as either food, or for the aquarium trade (Carr et al. 2013). The report also noted that fishing not only provides the cheapest source of animal protein, it is a major source of income for those living near water bodies in Uganda and the DRC (Lakes Albert and Edward), and particularly for the most destitute of people (ADF 2003). However there are indications that fish populations are declining, for example, people living around Lake Edward [in the DRC] have begun cultivating crops to lessen the impact of declining fish stocks (Alinovi et al. 2007).

We therefore need to make informed decisions regarding the future of any development within the Lake Edward basin (not just the Virunga National Park), and this needs to adequately incorporate any potential impacts to biodiversity and human society, it cannot just be based on the profits and dollar ‘benefits’ from the development. The age old excuse of “but there is no information to do this…” is no longer valid for Africa. However, there are many similar developments planned throughout the world and it is all the more important that such data are made available for the globe’s freshwater ecosystems. Unfortunately, it is currently unavailable for more than 50% of the world’s wetlands and a lack of funding is hindering efforts to fill this information gap. We can’t expect to have sustainable development if there is no baseline information set on freshwater biodiversity. We can broker deals, improve governance structures etc. but all needs to be underpinned by sound information on the biodiversity that enables these ecosystems to function sustainably.

All of IUCN’s freshwater biodiversity data (see the Biomatrix), including datasets produced as part of our participation in the Biofresh Project such as global freshwater shrimp assessments, New Zealand freshwater biodiversity assessment, and global freshwater turtle distributions will be included in the Biofresh Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas along with other non-biodiversity freshwater related data.

For more information on IUCNs work on freshwater biodiversity contact – Kevin Smith (Kevin.Smith@iucn.org) or William Darwall (William.Darwall@iucn.org)

*note: search for ‘Freshwater Biodiversity Browser’ within the ESRI App

References

ADF (2003) Multinational. Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda. Lakes Edward and Albert Fisheries (LEAF) Pilot Project. Nile Equatorial Lake Subsidiary Action Program (NELSAP). Nile Basin Initiative. Agriculture and Rural Development Department.

Alinovi, L., Hemrich, G. and Russo, L. (2007) Addressing Food Insecurity in Fragile States: Case Studies from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia and Sudan.

Carr, J.A., Outhwaite, W.E., Goodman, G.L., Oldfield, T.E.E. and Foden, W.B. 2013. Vital but vulnerable: Climate change vulnerability and human use of wildlife in Africa’s Albertine Rift. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 48. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. xii + 224pp.

Snoeks, J. (2000) How well known is the ichthyodiversity of the large East African Lakes? Advances in Ecological Research 31: 553–565.

On the clock: new technique improves precision of extinction predictions by giving a timeframe

The Salt Creek pupfish, found in Death Valley National Park in California. A new BioFresh study predicts the Death Valley river basin may lose one or more of its few fish species to climate change within the century. Source: Encyclopedia of Life. Author: Jason Minshull

The Salt Creek pupfish, found in Death Valley National Park in California. A new BioFresh study predicts the Death Valley river basin may lose one or more of its few fish species to climate change within the century. Source: Encyclopedia of Life. Author: Jason Minshull

Predicting which species will be the casualties of climate change is a challenging task – but forecasting extinctions within a policy-relevant interval is even more difficult. Studies often use habitat loss to predict how many species will go extinct, but not how long that process will take. An important new BioFresh study lead by Pablo Tedesco and colleagues and reported in the Journal of Applied Ecology tackles this problem head-on. By building a modelling technique that predicts riverine fish extinctions by 2090, the study develops a meaningful timeframe for policy. A key finding is that climate change may have little effect in most rivers in the next 80 years, especially when compared to other anthropogenic impacts.

To develop effective actions and targets, policymakers need information about extinction threats within a relevant time-scale: the time between prediction and extinction represents a “window of opportunity” where species may still be saved. The EU’s Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 specifically aims to reverse biodiversity loss, as does Aichi Target 12 under the Convention on Biological Diversity, which calls for preventing the extinction of known threatened species. Good planning also means figuring out which threats are the most urgent.

To determine how climate change drives extinctions, researchers have relied on the so-called “species-area relationship” – the greater the area, the more species will be found there. By estimating how much of a particular habitat area will become unsuitable due to climate change, scientists can predict how many species will also eventually disappear. But the time lag can range from decades to millennia, which limits its usefulness for policy. BioFresh partners Pablo Tedesco and his colleagues, however, build on previous work that calculates the relationship between area and true extinction rates. They use that relationship to estimate how habitat loss from climate change will change extinction rates in over 90,000 river drainage basins worldwide, and then predict how many species will be threatened with extinction in a smaller set of the rivers by the year 2090.

The good news for fish is that overall, these new models predict that even under a “pessimistic” climate change model, less than one-quarter of the drainage basins should lose habitat. On average, those basins that do are predicted to have around a 24% higher extinction rate. The effects should concentrate in arid, semi-arid, and Mediterranean climates, especially in the southwest USA, Mexico, southern America, northeast Brazil, northern and southern Africa, southern Europe, western and middle Asia, and Australia. Using actual species numbers, the study found that only 20 out of 1,010 basins would lose species by the year 2090, with the number of species lost ranging from 1 to 5.

Extinction rates in Western Australia’s Robe river basin are predicted to accelerate by over 340%, translating to about two species in the next 80 years, as the river loses water to climate change. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Author: SyntaxTerror

Extinction rates in Western Australia’s Robe river basin are predicted to accelerate by over 340%, translating to about two species in the next 80 years, as the river loses water to climate change. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Author: SyntaxTerror

These findings give climate change a much smaller role in driving extinctions than in other studies – particularly when compared to other anthropogenic pressures. In Central and North America, human impacts have driven 47 species extinct over the last century in 20 river basins, a rate 130 times greater than that predicted for climate change.

Although Tedesco and his colleagues point out that other effects of climate change could also drive extinctions, such as rising water temperatures or changing seasonal variability and extreme events, they stress that ongoing factors such as habitat degradation, overexploitation, eutrophication and invasive species are more pressing. Such immediate issues feature prominently in existing international and national policy; for example, a dedicated legislative instrument on invasive alien species is due to be adopted this year under the EU Biodiversity Strategy. “There still is a chance to counteract current and future fish species loss [by] focusing conservation actions on the other important anthropogenic threats generating ongoing extinctions in rivers,” comments Tedesco.

*Tedesco PA, Oberdorff T, Cornu JF, Beauchard O, Brosse S, Dürr HH, Grenouillet G, Leprieur F, Tisseuil C, Zaiss R & Hugueny B (2013). A scenario for impacts of water availability loss due to climate change on riverine fish extinction rates. Journal of Applied Ecology (online).

Does ecosystem services need a radical critique? In conversation with Prof Veronica Strang

After Veronica Strang presented her insights on bioethics developed through ‘thinking with water’ (see last post), I discussed with her the relevance of her thinking to policy and on-going discussions on the ecosystem services framework.

Several of Veronica’s points have stuck with me. One was her comment that we see ourselves as rational beings, yet in Ecosystem Services we are adopting a policy frame that places humans outside systems and this seems irrational! A second was her reflection that ‘if you reframe cultural meaning as an ecosystem service it is sort of missing the point of culture!”

I am sure you will find this video conversation with Veronica thought provoking and challenging. It reinforces my view that the ecosystem services policy frame would benefit from a radical and multi-disciplinary academic critique. Please share you thoughts and reflections on the issues raised with other readers of this blog via the comments box.

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Freshwater Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Professor Veronica Strang: Thinking with Water

The EC funds BioFresh to strengthen the scientific basis of policies intended to conserve biodiversity. Increasingly our science – the questions, analysis and communication of our findings – need to be aligned with the Ecosystem Services Framework. Demonstrating links between freshwater biodiversity and ecosystem services requires sophisticated and multi-scalar understandings of freshwater ecosystem processes and function, something that may be beyond current scientific capacity. Reflecting this situation, I have heard several BioFresh colleagues express concern that the ESF marginalises the ethical basis of policies linked to freshwater biodiversity.

It was for this reason that I asked Martin Sharman to contribute his perspective on the Ethics and Ecosystem Services. His post is already No4 in the BioFresh rankings of most viewed posts: it promoted a rich discussion on the LinkedIn Biodiversity Professionals group. There is clearly a desire to discuss ethics!

A little while ago, while herding my children out to school, I caught on the radio the phrase “water is good to think through a new bioethics”. The lady talking was Professor Veronica Strang, Director of the Institute of Advanced Study at the University of Durham. Veronica kindly agree to share her thinking with us in this video presentation. Her fascinating and deep insight adds a cultural anthropology perspective to the discussion initiated by Martin and bears direct relevance to the issue of oil exploration in Lake Edward/Virunga National Park introduced by Susanne Schmitt.

Please post your reactions to Veronica’s video presentation in the comments box and discuss with others.

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Freshwater Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

This guest post by Dr Susanne Schmitt flags the significance for Africa’s freshwater biodiversity of WWF’s major new campaign to stop oil exploration in the Virunga World Heritage Site. Susanne is WWF-UK’s Extractive and Infrastructure Manager.

This guest post by Dr Susanne Schmitt flags the significance for Africa’s freshwater biodiversity of WWF’s major new campaign to stop oil exploration in the Virunga World Heritage Site. Susanne is WWF-UK’s Extractive and Infrastructure Manager.

Today my organization launched a global campaign to stop oil exploration by the British oil company SOCO International in Virunga National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Virunga is famous as Africa’s first National Park (established 1925) and for its Mountain Gorillas. Virunga is the most biologically diverse protected area in Africa, including 216 endemic species. Based on this outstanding universal value Virunga National Park was declared a World Heritage Site in 1979, becoming one of only 193 natural WHS, which altogether cover less than 0.5% of the earth surface. Conservationist have bravely worked to protect the park in the face of the spill-over impacts of the Rwandan genocide (800,000 refugees living within the park for several years) and repeated civil unrest and conflict: in the last decade 130 rangers have given their lives defending this WHS against poachers and other incursions. WWF has decided its time to “Draw The Line”. We can’t let these efforts and sacrifice go to waste by risking to lose the park for commercial gain, because Soco is allowed to search for oil.

Map of Virunga National Park and World Heritage site showing Block V owned by Soco and the overlap with Lake Edward.

Soco is a FTSE 250 listed company that operates in the DRC Congo under the subsidiary, Soco Exploration and Production DRC Sprl (Soco). It has a license to explore for oil in the southern part of the park : Block V (see map) covers 2/3rds of the area of Lake Edward (the remaining 3rd is in Uganda). WWF is calling for Soco to pull out of Virunga and to publicly commit to stop oil exploration and exploitation in Virunga and to respect the Park’s current boundaries, in addition to publicly commit to respecting all World Heritage Sites and appropriate buffer zones. Following successful campaigning by WWF France, Total – who hold the Block III concession, which overlaps with the north of Virunga NP – have committed to stay outside the current boundaries of Virunga National Park, but have not made the wider commitment to respecting the boundaries of all WHS. The only major oil company that has made such a global commitment is Shell. We want Soco to act responsibly and do the same.

© naturepl.com/Christophe Corteau/WWF-Canon

I am appealing to freshwater scientists, policy makers and managers to support us in this campaign. Lake Edward together with Lake Albert feeds the White Nile. It is a Ramsar site, Important Bird Area and Key Freshwater Biodiversity Area. Lakes Malawi and Tanganyika are the most species rich areas in the Eastern African region with a maximum of 382 species recorded within a single 28 x 28 km grid cell, but Lakes Victoria, Albert, George, and Edward are close behind with up to 160 species recorded within a single 28 x 28 km grid cell.

Lake Edward’s productivity fell following the decimation of its 25,000 strong hippopotamus herd (the largest in Africa) during the civil unrest (1990-2007) but the hippo population and the lake’s fisheries upon which 28,000 jobs depend are recovering. The WWF-commissioned report ‘The Economic Value of Virunga” puts the current fisheries value at US$ 30m possible, which could rise to as much as US$ 90m with better management and restored hippo populations. Lake Edward and its wetlands are an irreplaceable part of our global natural heritage they deserve to be restored not damaged further.

© naturepl.com/Karl Amann/WWF-Canon

Generally speaking lakes are more bounded than, for example, the marine environment and thus the impacts of spills and other accidents could be serious and long lasting. This is particularly the case in the African Great Lakes due to long water retention times and low flushing rates, making them particularly vulnerable to pollution. Oil exploration involves seismic surveys from ships followed by test drilling. Seismic booms –generated with the use of explosives – are reported to cause localised fish kills and may have wider impacts on ecosystems and livelihoods. Industry insiders have told WWF that test drilling without leaks of oil or injected chemicals would be very difficult to achieve.

If Soco finds commercial viable oil reserves then it is likely to proceed to exploration or may sell the asset on to another oil company. Eastern DRC has a history of conflict involving multiple rebel factions, financing their operations from, so called, conflict minerals (diamonds, gold, coltan). Oil would potentially be adding another conflict resource, as pointed out by the International Crisis group’s 2012 report, Black Gold in the Congo. The building and operating of an oil infrastructure in this unstable context would be reckless from both environmental and human rights perspectives.

© naturepl.com/Edwin Giesbers/WWF-Canon

Lake Edward is not an isolated case. The string of Rift Valley lakes are in the spotlight for oil exploration: Lakes Albert, Tanganyika and Malawi all have active exploration concessions. As well as flagging wider threats to African freshwater biodiversity, WWF’s campaign highlights the bigger issues of apparently growing pressure to extract oil and minerals from within the boundaries of natural world heritage sites – see for example the threats to the Great Barrier Reef from plans for a huge port development to export coal.

You can support our campaign in several ways. By signing the petition on our campaign web-site, by re-tweeting us – #SOSvirunga, by adding comment to on-line news reports and by briefing yourself on WWF’s calls to Soco, governments and investors in our campaign advocacy report. In addition I would be grateful for comments on this post that could help strengthen the freshwater arguments of our campaign.

Thanks in advance.

What rivers do for us

In this latest contribution to our special feature on freshwater biodiversity and ecosystem services, Dr Christian Feld reviews the services provided by river ecosystems

River ecosystems encompass river channels and its floodplains and form a diverse mosaic of habitats with the riparian area at the transition zone between the land and water. During flood events, water and sediment are transported onto the floodplain and provide the nutrients that render river ecosystems highly productive. Conversely, floodplains (and other wetlands) constitute important sinks of river nutrients and sediments and, hence, contribute substantially to a river’s self-purification. They act as a sponge and regulate the water volume, as they cut off flood peaks and release water during low-flow conditions. Floodplains, especially the riparian areas, provide the river channel with carbon (organic matter) which is essential for sustaining riverine plant, animal and micro-organism communities in many regions of Europe.

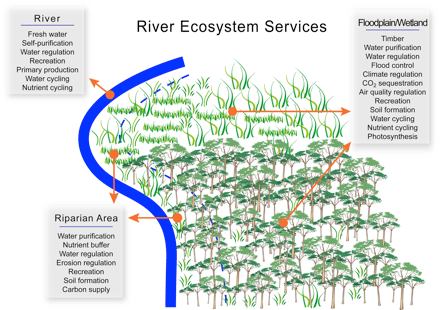

Looking more precisely at the specific services provided by river ecosystems, their important role for human well-being becomes obvious. Nearly everywhere on Earth, people depend on rivers for fresh water supply and sanitation purposes. But there are many more services linked with rivers and floodplains besides these fundamental human needs. This schematic provides an overview of the major provisioning (e.g. fresh water and timber supply), regulatory (e.g. water and erosion regulation, self-purification), cultural (recreation and ecotourism) and supporting (e.g. soil formation, nutrient and water cycling) services provided by freshwater ecosystems.

Major ecosystem services provided by rivers, riparian areas and floodplains/wetlands in Europe.

Harrison, P.A., Gary W. Luck, G.A., Feld, C.K & M. T. Sykes (2010) Assessment of Ecosystem Services. In: Settele, J., Penev. P., Georgiev.T., Grabaum, R., Grobelnik, V., Hammen, V., Klot.S., Kotarac, M., & IKuhn (Eds): Atlas of Biodiversity Risk. Pensoft, Sofia, pp 8-9.

Ecosystem services are sometimes valued in monetary terms for use in policy- and decision-making. This is relatively straightforward for provisioning services such as water and timber supply where market values exist. However, it is more difficult and often controversial for many regulatory and supporting services for which the direct benefits to people are not as clear. Nevertheless, several studies have provided values for river and floodplain ecosystem services. The Danube floodplain and wetlands, especially their regulatory role as a nutrient sink, have been valued at 650 Million Euro per year (Gren et al. 1995). On a global scale, an annual total value of 4,879 Trillion US$ has been estimated for wetlands and 3,231 Trillion US$ for floodplains (including swamps) or, altogether, around 24 % of the total annual ecosystems services’ value on Earth (Costanza et al. 1997).

In agricultural landscapes, mixed riparian buffers composed of trees and grass strips can effectively retain sediment from surface run-off and nutrients from the upper groundwater layer (Dosskey 2001). Photo of River Nuthe in Brandenburg, Germany taken by Christian Feld.

Read other articles in our Special Feature on Freshwater Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Details of the scientific papers mentioned

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., groot, R.d., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R.V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R.G., Sutton, P., & Belt, M.v.d. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387, 253-260.

Dosskey, M.G. (2001) Toward quantifying water pollution abatement in response to installing buffers on crop land. Environmental Management, 28(5), 577-598.

Gren, I.-M., Groth, K.-H., & Sylvén, M. (1995). Economic values of Danube floodplains. Journal of Environmental Management, 45, 333-345.