Wild Swimming in Europe: Freshwater matters

Wild Swimming: from http://www.outdoor-sport-leisure.net/wild-swimming.htm (Kate Rew / Wild Swim)

Wild swimming in rivers, lakes and streams is increasing in popularity across Europe, as people discover (or, perhaps, rediscover) the pleasure of swimming in freshwaters: unaffected by chlorinated water, stark lights and tightly regimented lanes.

Last week, the findings of the most recent European Union Bathing Water Directive (data here) were published by the European Environment Agency, showing the cleanliness of over 22,000 freshwater and saltwater swimming spots across Europe, from inner city ponds to rural rivers, shown in the Guardian data-blog map below (click through to the interactive version):

This data can also be explored through these interactive sites:

However the news for freshwater wild swimmers isn’t positive, according to the report:

“In 2010, 90.2 % of inland bathing waters in the European Union were compliant with the mandatory values during the bathing season, a figure 0.8 percentage points higher than in the previous year. The number of inland bathing waters complying with the more stringent guide values decreased by 10.2 percentage points compared to 2009, reaching 60.5 %”

(n.b. guide values describe the standard for “excellent” bathing water quality set by the EU)

This means that c.10% of European freshwater swimming sites does not reach the minimum safety standards set by the EU, potentially posing a health hazard, and serving as a worrying indicator for the health of the wider ecosystem, whilst c.40% do not reach the ‘excellent‘ guide values of water quality. Read more…

Steppe landscape. Image: Creative Commons: Steyr / Picasa

By Dr. Aaike De Wever, Science Officer for the BioFresh project at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science, and co-ordinator of the freshwater biodiversity data workflow and creation of the public data portal. He can be emailed at data@freshwaterbiodiversity.eu and he tweets @biofreshdata.

By Dr. Aaike De Wever, Science Officer for the BioFresh project at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science, and co-ordinator of the freshwater biodiversity data workflow and creation of the public data portal. He can be emailed at data@freshwaterbiodiversity.eu and he tweets @biofreshdata.

—

When I started to work on the BioFresh project a year ago, I still very much needed to figure out what a freshwater biodiversity information platform and data portal was going to look like. Obviously I immediately had a closer look at the work of my colleagues at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science and the Belgian Biodiversity Platform, especially at SCAR-MarBIN (initiative on marine Antarctic biodiversity data) and the Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment (FADA; authoritative species lists for freshwater organism groups). After some discussion and reading, however, I soon came to realize that the aim for BioFresh was somewhat different…

The project description reads:

“The freshwater biodiversity information platform is supposed to bring together, and make publicly available, the vast amount of information on freshwater biodiversity currently scattered among a wide range of databases. Previously dispersed and inaccessible data will thus be made available to policy makers, scientists, planners and practitioners. Integration of these data in scientific analyses will lead to better insights in the status and trends of freshwater biodiversity and its ecosystem services and provide scientific support for its management.”

Now, so far the theory, but how do we actually achieve this goal? Read more…

Madagascan mayfly hyper-diversity

Proboscidoplocia(Image courtesy of the Museum of Zoology, Lausanne http://www.zoologie.vd.ch)

Our final post in this series (no longer just a week…) is by BioFresh partner Dr Michael Monaghan from the IGB in Berlin, highlighting the importance and curiosity of mayfly diversity in Madagascar.

—

Mayfly larvae are well known to freshwater biologists and anglers. The larvae are found in all types of streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds. The adults are famous for their evening swarms and flying behavior that fly-fishing seeks to emulate. Perhaps less well known is that mayflies are ancient. Their fossil record dates back nearly 300 million years and genetic studies have confirmed that they are the oldest flying insects (together with the dragonflies). Their characteristic unfolded wings are also evidence for their ancient origins, as is their sexually immature life history stage that is unique among the insects.

Today there are more than 3000 recorded species of mayflies on Earth. But the real number is higher because several regions remain almost entirely unexplored. This is particularly true in the tropics, where most of the mayfly biodiversity on Earth is concentrated. One example is a study in 2000-2001 of less than 10 x 10 km of rainforest in Borneo that revealed 50 new species!

Much of what we know about mayflies in the tropics comes from research conducted on Madagascar. Madagascar is the fourh largest island on Earth and is often referred to as the eighth continent. Together with the Indian Ocean islands (Seychelles, Comoros and Mascarenes) it constitutes a global biodiversity hotspot. Famous for its lemurs and chameleons, Madagascar also is home to a high biodiversity of mayflies. More than 70 species have been described since the mid-1990s, including many strange ones! The largest mayflies in the world occur on Madagascar (Proboscidoplocia) and I have myself caught individuals 7 cm long. At least three species on Madagascar are predators of other stream insects – a role normally reserved for stoneflies and caddisflies. Perhaps strangest of all, Prosopistoma was first described from Madagascar in 1833. It looks so unusual that it was thought to be a crustacean for nearly 100 years.

Because many species remain unknown to science, a best guess at the moment is that there are at least 200 species of mayfly on Madagascar. To date, only one species is known to occur anywhere else (Cloeon smaeleni is also found in southern Africa and on Reunion). This means more than half the known diversity of Africa occurs on only 1.9% of its land area, and that nearly 7% of the Earth’s total diversity lives on an island the size of France, and that these species occur nowhere else. Unfortunately, this diversity is under threat from human pressures and from a lack of freshwater resource management.

Image 3. Afroneuris (Image courtesy of the Museum of Zoology, Lausanne http://www.zoologie.vd.ch)

I have been fortunate enough to spend nearly 8 months in Madagascar over the past 8 years, working with Malagasy, French, Swiss, South African, and British scientists to better understand the diversity of mayflies throughout the island. More importantly, I have been priveleged to work with and help train 8 Malagasy students in field entomology. It is an island of great contrasts – dry grasslands, tropical rainforests, coastal mangroves, alpine meadows, tsingy, wetlands, and agricultural landscapes. Each of these areas harbors unique species.

Additional reading:

Elouard J-M, Gattolliat J-L, and Sartori M. 2003. Ephemeroptera, Mayflies pp639-644 in The Natural History of Madagascar (eds SM Goodman & JP Benstead). University of Chocago Press.

Barber-James HM, Gattolliat J-L, Sartori M, Hubbard M. 2008. Global diversity of mayflies (Ephemeroptera, Insecta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595:339-350 (10.1007/s10750-007-9028-y)

Monaghan MT, Gattolliat J-L, Sartori M, Elouard J-M, James H, Derleth P, Glaizot O, de Moor FC, Vogler AP. 2005. Trans-oceanic and endemic origins of the small minnow mayflies (Ephemeroptera, Baetidae) of Madagascar, Proc Roy Soc B 272:1829-1836. (10.1098/rspb.2005.3139)

The mayfly and the Angler’s Monitoring Initiative

Last week’s mayfly special was so popular that we couldn’t publish all the submitted articles. So here, as an excellent, hopeful penultimate post, Louis Kitchen from the Riverfly partnership discusses the role of the Angler’s Monitoring Initiative in British mayfly conservation

—

A big hatch of mayflies must rank among the most enthralling wildlife spectacles that the UK has to offer – especially to those who operate in and around the river. Birds, bats, fish and fishermen are among those who appreciate the mayfly. And among these it is surely not just the fisherman who has felt the effects of a decline in the frequency and scale of hatches.

A big hatch of mayflies must rank among the most enthralling wildlife spectacles that the UK has to offer – especially to those who operate in and around the river. Birds, bats, fish and fishermen are among those who appreciate the mayfly. And among these it is surely not just the fisherman who has felt the effects of a decline in the frequency and scale of hatches.

Many factors can affect populations of mayflies and other freshwater invertebrates. Intensive agriculture and industry has resulted in a large number of our watercourses being modified, and this is certainly among the causes of a decline in our more sensitive species. Occasional pollution incidents can also have devastating effects on invertebrate populations, which may then take a long time to recover – in heavily impacted rivers a full recovery may never happen. Most people associate pollution incidents in rivers with dead fish, but by the time pollution has become severe enough to kill fish, a lot of invertebrates will have been wiped out.

It is this sensitivity to pollution that makes invertebrates incredibly useful for monitoring our rivers. By looking at some of the most sensitive invertebrate groups, anglers and other stakeholder groups are keeping tabs on water quality in their local areas through the Angler’s Monitoring Initiative (AMI). The focus is on the riverflies – stoneflies, caddisflies and mayflies – and the principle is quite simple: If a monitor takes a sample at a site one month, and finds healthy populations of riverflies, then returns the next month and most of them appear to have vanished, then it is likely that there has been a problem at some point in the intervening month.

The AMI was officially launched by The Riverfly Partnership in 2007, and there are now over 50 groups involved, with around 500 volunteers monitoring sites across the UK. Groups work closely with the local statutory bodies – the Environment Agency, Scottish Environment Protection Agency and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. If a decline in riverfly populations is detected then the statutory bodies are contacted and will be able to assess and deal with the problem. By monitoring every month the volunteers pick up on declines in water quality that may otherwise have gone unnoticed, and ensure early action to prevent problems escalating. In some instances severe pollution incidents have been picked up on; there have been three prosecutions of polluters, resulting in fines for the companies involved, that have come about because of AMI monitoring.

The AMI was officially launched by The Riverfly Partnership in 2007, and there are now over 50 groups involved, with around 500 volunteers monitoring sites across the UK. Groups work closely with the local statutory bodies – the Environment Agency, Scottish Environment Protection Agency and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. If a decline in riverfly populations is detected then the statutory bodies are contacted and will be able to assess and deal with the problem. By monitoring every month the volunteers pick up on declines in water quality that may otherwise have gone unnoticed, and ensure early action to prevent problems escalating. In some instances severe pollution incidents have been picked up on; there have been three prosecutions of polluters, resulting in fines for the companies involved, that have come about because of AMI monitoring.

It is important for the future of British rivers that communities take an interest in their well-being. By empowering local people to look after the water quality in their rivers, we allow rivers affected by pollution to improve naturally without suffering further setbacks. In this way we may see the return of huge swarms of mayflies swirling above the water – good news for everyone, especially the birds, bats, fish and fishermen.

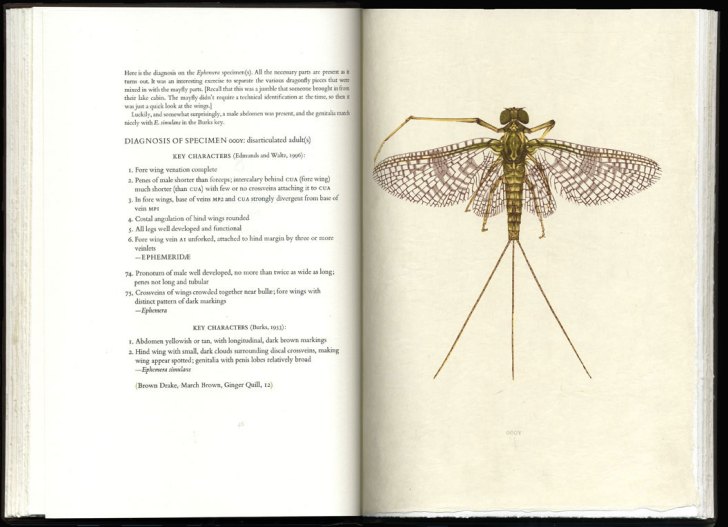

Mayflies of the Driftless Region

Approaching the last of the guest posts for the BioFresh ‘Mayfly week’, Gaylord Schanilec – an artist and author from Wisconsin, USA – highlights the role of mayflies in art, through a discussion of his book ‘Mayflies of the Driftless region’. His last sentence (“Scientists and artists do basically the same thing: they observe the world around them, and record their observations as best they can.”) strikes me as one of the most eloquent expressions of the potential for overlaps between art and science that I’ve read. Enjoy!

Approaching the last of the guest posts for the BioFresh ‘Mayfly week’, Gaylord Schanilec – an artist and author from Wisconsin, USA – highlights the role of mayflies in art, through a discussion of his book ‘Mayflies of the Driftless region’. His last sentence (“Scientists and artists do basically the same thing: they observe the world around them, and record their observations as best they can.”) strikes me as one of the most eloquent expressions of the potential for overlaps between art and science that I’ve read. Enjoy!The mayfly in music

To finish our week of mayfly posts, we’ll take a quick look at how the mayfly’s temporary, transient life-cycle has inspired many songwriters in search of a suitable metaphor. Is there potential for the engagement we get with nature through music to translate into positive conservation action?

Belle and Sebastian ‘Mayfly’ (from If You’re Feeling Sinister, 1996)

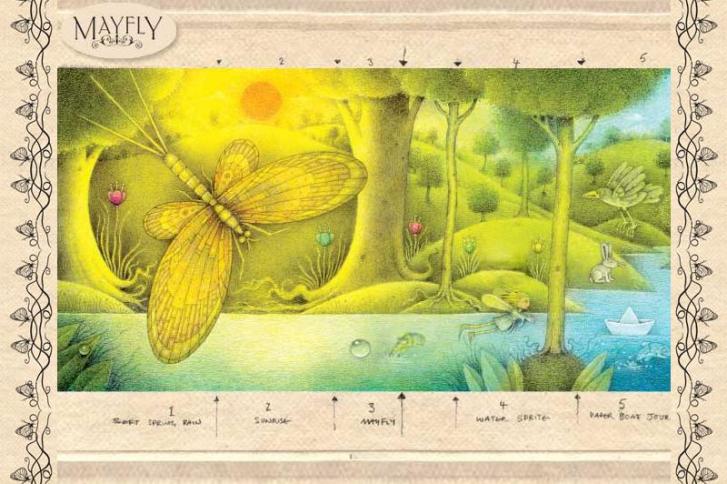

Dave Kirk’s Mayfly LP traces the insects ephemeral existence through the course of an album. Click here to be taken to the interactive website following this journey.

In Kirk’s own words: “The album is a story, in musical form, of what an imaginary mayfly sees and feels in her day;s life on the riverbank, from when she first touches “Soft Spring Rain” at the beginning of her life at Sunrise onto the ‘Mayfly’ experiencing her first smile when meeting with a ‘Water Sprite’ and then following a ‘Paper Boat Journey’ down a gentle stream into a restless river and back into the safety of a quiet stream”.

In Kirk’s own words: “The album is a story, in musical form, of what an imaginary mayfly sees and feels in her day;s life on the riverbank, from when she first touches “Soft Spring Rain” at the beginning of her life at Sunrise onto the ‘Mayfly’ experiencing her first smile when meeting with a ‘Water Sprite’ and then following a ‘Paper Boat Journey’ down a gentle stream into a restless river and back into the safety of a quiet stream”.

Does anyone have any other suitable suggestions?

Long-tailed Mayflies (Palingenia longicauda) hatching in the Tisza River -- Solvin Zankl/Visuals Unlimited,Inc. ©

Guest curator in the Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities: Following his extremely successful caddis fly entry into the Cabinet in March, BioFresh partner Dr Daniel Hering returns to showcase Palingenia longicaudia, or the Tisza mayfly, Europe’s largest mayfly. You can read the full entry (and delve through dozens of other freshwater curiosities) here.

The mayfly and the fly fisherman

Guest author: Malcolm Greenhalgh, naturalist, fly fisherman and author of ‘The Floating Fly’ and ‘The Mayfly and the Trout’

—

I am taking mayflies as being the Order Ephemeroptera, that I prefer to call the upwinged flies, as the term causes confusion with the real mayfly, Ephemera danica, in which the dun (or subimago) and spinner (imago) are on the wing in the period May-early July.

Traditionally North Country (of England ed.) fly-fishers fished a style that is completely different to the style fished on southern chalk streams. There, from about 1870, the use of the dry fly became so dominant that it became the unquestioned rule. There a floating fly with some resemblance to the natural fly is cast to a trout that has just taken a real fly from the water surface. Here in the North Country (and I include Derbyshire/Staffordshire in this) finely dressed wet flies were mostly used that have only a passing resemblance of the real fly, and they fish below the surface (usually in the top 2-5cm). If trout are rising, they may be cast to identified fish; but mostly these North Country wet flies were fished into any likely palce that might hold a trout. In recent years this traditional North Country style has diminished greatly in popularity, and many fly-fishers in this region now use floating flies.

Waterhen Bloa (left) is an example of this style of traditional fly, with its sparse body and few soft hackle fibres.

In the late 19th century and through most of the 20th, fly-fishers were mostly concerned with size and colour in their artificial floating flies because they believed that trout could spot subtle shades and used colour to identify those flies that they ate. In one famous instance, even the turbinate eyes were matched by using ‘One turn of horse hair, dyed van Dyke brown.’ But from the 1950s or 1960s we realised that trout do not have such an acute vision when looking at a floating fly, and that size, shape (silhouette) and position in the water in relation to the surface film are far more important. This latter has become vital, allowing fly-fishers to catch trout that they might otherwise not have caught with traditional dry flies as used on southern chalk streams. So let me now describe the four categories of flies that we use to catch trout eating mayflies. Read more…

Why stream mayflies can reproduce without males but remain bisexual: a case of lost genetic variation

Continuing our day of fascinating new scientific research on the mayfly, Dr David Funk, insect biologist at the Stroud Water Centre, USA and nature photographer reports on his recent paper “Why stream mayflies can reproduce without males but remain bisexual: a case of lost genetic variation” from the Journal of the North American Benthological Society, explaining the idea of ‘parthenogenesis’…

—

Mayflies spend months to years in the water as aquatic larvae, but they are best known for their highly synchronous and often spectacular adult emergences and their extremely short adult lives. For example, individuals of the North American species Dolania americana spend 2 years in the water (8 months as eggs followed by 28 months as larvae) before emerging about an hour before sunrise on one of only about 4 days spread over a two week period in May. In a desperate rush against time hoards of adults mate and lay eggs. Thousands of spent individuals lie dead on the water surface by the time the sun comes up.

Not all mayfly species are quite this extreme, but the adult life of a mayfly is always brief. Adult mayflies emerge from the water with their eggs ready to be fertilized and laid and, because adults cannot feed (their mouth parts are atrophied), they have a finite amount of energy available with which to accomplish this. Mating typically occurs at highly specific locations and times of day, so females face a very narrow window of opportunity to find a mate. Read more…

Wrapping bridges for mayfly conservation?!

Guest author: BioFresh partner Szabolcs Lengyel (Assistant Professor of Ecology, University of Debrecen, Hungary) takes inspiration from the art world to suggest a novel solution to an unusual ecological problem for mayfly populations.

—

What’s a mayfly to do when she meets a bridge?

One would assume that she flies over it. Or under it.

Still, according to a new study published in Journal of Insect Conservation, eighty-six percent of long-tailed mayflies (Palingenia longicauda) approaching a bridge never cross and turn back from it. To uncover the background of this peculiar behaviour, scientists from the University of Debrecen and Eötvös University from Budapest teamed up to study the flight of female mayflies on river Tisza in NE-Hungary.

The mayfly’s life is a fascinating one. Larvae develop in the riverbank for three years, then in one early summer afternoon they swim from their burrows to the water surface. Males come up first, moult on the water surface and fly to the riverbank for another, final moult. By the time they finish their second moult, female larvae emerge and undergo their own moult on the water surface. After mating with the males or escaping from them, female mayflies fly upstream. This flight presumably compensates for river flow and ensures that eggs deposited upstream reach the bottom where the egg-laying females had lived as larvae.

It is this compensatory flight which is interrupted by bridges. Because mayflies never actually touch the bridge, researchers focused on the optical properties of the bridge. It had been previously discovered that mayflies use a special signal of polarized light to identify water as such. Thus, the team performed measurements of polarized light at the bridge, enabling scientists to see with the eyes of the mayflies. Read more…