Planning for change: the origin, distribution and conservation of endemic fish species

Achondrostoma: a tiny fish species endemic to Iberia. Image: Ana Maria Geraldes

A new journal article published by BioFresh partners has revealed intriguing new findings about the global origins and distribution of river fish species, with important consequences for their conservation. The article “Patterns and processes of global riverine fish endemism” was published in Global Ecology and Biogeography, seeking to provide a means to identify areas of high conservation interest based on the present and future evolutionary diversification potential of fish species.

Lead author Pablo Tedesco from the Natural History Museum in Paris explains: “We distinguished between two kinds of endemic freshwater fish species: those that originated within a drainage basin by radiation and did not disperse after; and those that were once widespread and reduced their range either by extinctions or by differentiation in one drainage basin.

Then we related these two kind of endemic species to historical, habitat, climatic and biological factors and found that the first category (originated from a small range) is occurring mostly in large drainage basins with a rather stable climatic history and having poor dispersal abilities. Contrarily, the second category of endemics (those that were once widespread) occur in highly isolated places (like islands or peninsulas) and mostly belong to families that originated in the sea. These findings point out that instead of focusing on endemic species to protect them, we should protect the places where species are created in order to preserve future diversity”.

These are fascinating findings which add to the growing discussion on how evolutionary processes can be incorporated into conservation planning. Understanding species histories and potential evolutionary futures is important for conservation managers looking to conserve species in the face of threats such as climate change and habitat loss. As such, this paper furthers our understanding of how we may prioritise effective conservation planning for freshwater fish species.

You can read the paper here.

Coming soon…the new BioFresh animation “Water Lives”

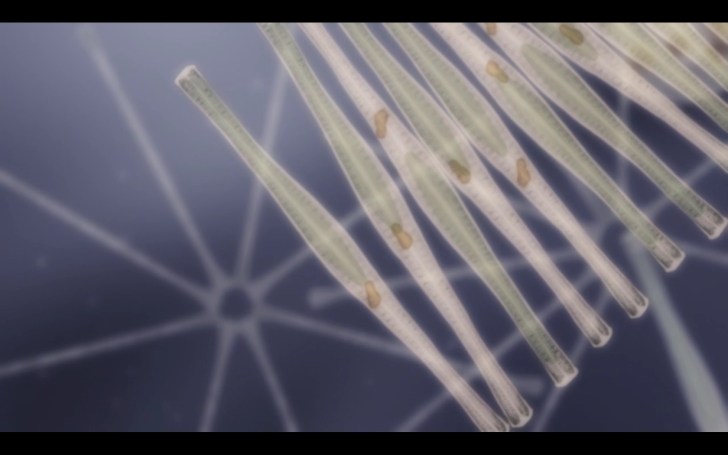

Animated diatoms in the forthcoming BioFresh animation "Water Lives"

We’re delighted to be able to share the amazing first images from the recently completed “Water Lives” science communication animation. Produced by BioFresh at Oxford University School for Geography and the Environment, the animation employs a team including an award-winning animator, a musician, a haiku poet and a team of freshwater scientists to raise awareness of the need to appropriately manage and conserve the complex, beautiful webs of life that make up our freshwater ecosystems.

We’re delighted to be able to share the amazing first images from the recently completed “Water Lives” science communication animation. Produced by BioFresh at Oxford University School for Geography and the Environment, the animation employs a team including an award-winning animator, a musician, a haiku poet and a team of freshwater scientists to raise awareness of the need to appropriately manage and conserve the complex, beautiful webs of life that make up our freshwater ecosystems.

More details will be revealed soon ahead of a premiere and release in the week of 26th March 2012. For now, enjoy the images!

New BioFresh publication: monitoring the ‘global reshuffling’ of species distributions and diversity

A Swedish freshwater landscape. Monitoring species distributions across a landscape at different levels of diversity remains a focus of much research. Image: Nuria Bonada

There is increased attention being paid to biotic homogenisation and differentiation following increased human pressures on ecosystems, biotic invasions and what the IUCN’s Jeff McNeely terms the ‘global reshuffling’ of species distributions. A new paper by BioFresh partners Sébastien Villéger and Sébastien Brosse develops a new mathematical metric based on species extirpation (local extinction) and non-native species invasions to measure and assess changes to biodiversity.

Sébastien Brosse outlines the basis of the paper “The loss of distinctiveness between biological communities, called “Biotic Homogenization”, has been measured using different indices (different mathematical formulations). In this paper we evaluated the relevance of these indices to measure Biotic Homogenization, and then we provide a tool to disentangle what determines homogenization. This tool will help us to better understand how human activities affect a measure of biodiversity called Beta-diversity (i.e. the taxonomic differences between localities).”

The article “Measuring changes in taxonomic dissimilarity following species introductions and extirpations”, published in the journal Ecological Indicators provides a significant step forward in quantifying and predicting human impact on the health and status of global ecosystems. You can access the article here.

What do alpha, beta and gamma diversity mean?

The paper by Villéger and Brosse refers to the concepts of alpha and beta diversity – but what do these terms actually mean? Many people are familiar with the term biodiversity, generally agreed to mean the variety of life on earth – from microorganisms to giant whales – and the ecosystems in which they live.

However, the idea of “biodiversity” is relatively recent concept, popularised in the 1980s. In the 1960s, Robert Whittaker – an American plant ecologist – proposed a three-tiered concept of species diversity across a landscape. Whittaker proposed that the total species diversity in a landscape (gamma diversity) is determined by the species diversity in sites or habitats at a local scale (e.g. an individual lake or field – alpha diversity) and the level of differentiation between these habitats (beta diversity).

Conservation policies provide inadequate protection for freshwater biodiversity and ecosystem services

Limpopo River, Mozambique. Image: Wikipedia

Current methods used to plan protected areas for conservation are not providing adequate protection for freshwater ecosystems and the ecosystem services they provide. There is a pressing need for more primary information on freshwater biodiversity status and distribution to support more effective conservation planning and investment. These are the key messages of a new journal article by BioFresh partner Will Darwall at the IUCN and colleagues, published in Conservation Letters.

Comprehensive assessment of freshwater biodiversity across Africa

The study represents the most comprehensive assessment of freshwater biodiversity across an entire continent. It combined the range maps for 4,203 freshwater species and 3,521 terrestrial species across Africa with data on IUCN Red List extinction risk, protected area coverage, large dam presence and rural poverty to analyse the status, threats and protection for freshwater biodiversity.

Terrestrial species act as poor surrogates for freshwater species

Darwall and colleagues found that terrestrial and charismatic species are poor surrogates for capturing the distribution and threat towards many freshwater species. As the authors state: “for fish, molluscs and crabs, results suggest that conservation priorities and investment targets based on our knowledge of birds, mammals and amphibians alone may not adequately represent these freshwater species”.

The authors argue that conservation research biased towards terrestrial and charismatic species means that our knowledge of global freshwater biodiversity patterns and trends is fragmented and incomplete. Because protected areas for biodiversity conservation are often planned using ‘surrogate’ species – where the protection of well-known and documented taxa is thought to act as ‘umbrella protection’ for those less well-known – freshwater ecosystems are currently under-protected from a myriad of human and climate based threats.

Fisherman on Lake Tanganyika. The number of known threatened species in the African Great Lakes increased based on the findings of this study. Image: Wikipedia

Conservation and ecosystem service needs not met by existing protected areas

The dynamic, trans-boundary nature of freshwater ecosystems mean that their conservation needs are often not met by protected areas planned around terrestrial ecosystems. The bias towards research on terrestrial biodiversity means that often freshwater systems are not congruent with existing protected areas.

Importantly, the study found that in Africa, areas of highest freshwater species richness and threat overlap significantly with areas where reliance on ecosystem services by humans is high. In addition, these areas are commonly under high pressures from humans. In this study, of the 4,203 freshwater species assessed, 26% were found to be threatened with global extinction. However, shortfalls in our knowledge of freshwater biodiversity meant there was insufficient information to assess the status of 741 freshwater species in the study, meaning the extinction threat level could be as high as 37%.

The River Nile in Cairo. Image: Wikipedia

Threats to freshwater ecosystems and human livelihoods

Why is this study important? Freshwaters represent one of the most threatened ecosystems globally – they contain over a third of the world’s known species and around a third of all vertebrates despite occupying less than 1% of the Earth’s surface. Human population growth and economic development threaten the health and integrity of many global freshwater ecosystems, compromising their ability to support biodiversity and provide ecosystem services such as irrigation, sanitation and food supply to humans.

The urgent need for targeted freshwater biodiversity research and funding

The key conclusion of the article is that there is a strong case for a shift in research and targeted investment towards freshwater biodiversity to reflect the value and importance of freshwater ecosystems and the services they provide. Better-known (often terrestrial) taxonomic groups do not act as adequate surrogates for freshwater species when planning conservation management. Improved data on freshwater species is needed to underpin the expansion of the existing network of protected areas to adequately protect threatened freshwater systems.

Source: Darwall, W. R. T., Holland, R. A., Smith, K. G., Allen, D., Brooks, E. G. E., Katarya, V., Pollock, C. M., Shi, Y., Clausnitzer, V., Cumberlidge, N., Cuttelod, A., Dijkstra, K.-D. B., Diop, M. D., García, N., Seddon, M. B., Skelton, P. H., Snoeks, J., Tweddle, D. and Vié, J.-C. (2011), Implications of bias in conservation research and investment for freshwater species. Conservation Letters, 4: 474–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00202.x

Links:

New study reveals Europe’s rivers under pressure

Catalonian mountain stream. Image: Nuria Bonada

A new press release from the European Commission states that: “the largest investigation to date into the extent of human-induced pressure on European rivers concludes that around 80% of rivers are affected by water pollution, water removal for hydropower and irrigation, structural alterations and the impact of dams, with 12% suffering from impacts of all four“.

The journal article “Multiple human pressures and their spatial patterns in European running waters” published in Water and Environment Journal by Rafaela Schinegger and colleagues at University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna assessed human pressures on freshwater ecosystems at 9330 riverine sites across 14 European countries. The study is part of the EU EFI+ project2 and is designed to give a high-resolution, European-scale assessment of the human threats to river ecosystems as a means of supporting the European Water Framework Directive.

Human pressures on freshwater ecosystems are only likely to increase in the future, meaning this study is important in providing an ecological baseline for rivers to be appropriately managed in the future. The findings will help allow vulnerable freshwater ecosystems to be identified, monitored and conserved under the river-basin system of management outlined by the Water Framework Directive.

You can read a summary of the paper through DG Environment or access the main paper at Water and Environment Journal.

Meet the BioFresh team: Thierry Oberdorff

Thierry Oberdorff

We continue our series of articles giving a ‘behind the scenes’ look at the work carried out by BioFresh scientists this week with an interview with Thierry Oberdorff from the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) in Marseille, France. The IRD has three main missions: research, consultancy and training. It conducts scientific programs contributing to the sustainable development of the countries of the South, with an emphasis on the relationship between humans and the environment.

1 What is the focus of your work for BioFresh, and why?

It will provide science-based answers to pressing conservation questions that are currently being asked by our societies.

Image: Thierry Oberdorff

3 Why is the BioFresh project important?

I can list two main reasons. First, freshwater ecosystems provide goods and services of critical importance to human societies yet are unfortunately among the most heavily altered ecosystems. However, efforts to set global conservation priorities have, until now, largely ignored freshwater diversity, thereby excluding some of the world’s most speciose and valuable taxa. There is thus an urgent need to fill the gap for freshwater biodiversity.

Secondly, as previously mentioned by Daniel Hering (another BioFresh partner) one of the major tasks of BioFresh is collating all possible freshwater biodiversity data and making them publicly available through an open portal, reducing in fine obstacles to data access for research.

Image: Thierry Oberdorff

4 Tell us about a memorable experience in your career

When a Aymara indian from Bolivian Altiplano showed me the diversity of colours of wild corn.

5 What inspired you to become a scientist?

I was just lucky. Being a researcher is obviously one of the most interesting jobs in the world.

6 What are your plans and ambitions for your future scientific work?

To go back to the tropics and contribute with local partners to the research development of southern countries.

What’s in a name: does the data publication metaphor work for primary biodiversity data?

Looking for a solution: a flamingo in Chile. Image: Nuria Bonada

In the process of collecting, collating and mobilising freshwater biodiversity data for BioFresh I routinely use the phrase “data publication” in order to convince data authors or holders to make their data publicly available. In a paper currently available for public review, Mark Parsons and Peter Fox discuss the applicability and limitations of the data publication metaphor for making data broadly available. As the authors state themselves, their paper is somewhat provocative. Looking at the responses at their blog, it created quite a discussion which I must say got me thinking as well…

Where and how? Citing biodiversity data

When looking at our work within BioFresh – which for me at least focuses on primary biodiversity data (basically the what, where, how and by whom an organism was observed or collected as defined by the Global Biodiversity Information Facility) – I must admit that I agree with most limitations Parsons and Fox attribute to the use of the term data publication. It is for instance true that there is no standard review process or mechanism for datasets which comes close to the well-accepted practice of peer-review for scientific papers. In addition, for primary biodiversity data made available through the GBIF network data holders can make data available without necessarily publishing a paper on it (e.g. data on museum collections). This isn’t a bad thing at all (see our previous posts on data sharing topics), but it doesn’t reflect the term data publishing in a strict sense very well). Finally, this data rarely carries a persistent identifier like a Digital Object Identifier (DOI).

As such, we merely use the term data publication to stress the fact that scientists making their data available on-line shouldn’t see this as an act of ‘giving away’ their work. Instead, it is seen as a way for their data to be reused and cited in other scientific work (e.g. large scale biodiversity modelling) and thus creating more visibility for their work. Citing a dataset in the absence of a published scientific paper does however not have the same value as a citation that can easily be tracked through scholarly search engines and taken into account in a citation score. So, yes, in a way the term data publication can be somewhat misleading.

What’s the alternative?

But is there a worthy alternative? The process of making primary biodiversity data available on-line demonstrates parallels to the widely adopted practice of submitting sequence data to publicly available databases such as EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ. For both primary biodiversity data and sequence data, authors need to supply a limited set of core data in a standardized format and these data may be part of a larger dataset e.g. also containing environmental data which is not made publicly available. If we only want to stress the process of making (primary biodiversity) data available, data submission seems a valuable alternative, especially as it sounds less voluntary than data sharing. But, until data sharing has become a common practice and/or is being enforced by journal editors, I believe a good alternative to the data publication metaphor for convincing scientists has yet to be found.

P.S.: I could further elaborate on the emerging topic of actual data papers in biodiversity science (e.g. Chavan & Penev 2011), but I’ll keep that for a follow-up post.

A new IUCN Red List for European freshwater fish, written by BioFresh partner Jörg Freyhof and Emma Brooks from the University of Southhampton, has been recently published. You can read it through the interactive Issuu magazine above, or download it here. More information on IUCN Red Lists is available here.

The Red List is: “a review of the conservation status of around 6,000 European species, including dragonflies, butterflies, freshwater fishes, reptiles, amphibians, mammals and selected groups of beetles, molluscs, and vascular plants, according to IUCN regional Red Listing guidelines. It identifies those species that are threatened with extinction at the regional level – in order that appropriate conservation action can be taken to improve their status. This Red List publication summarizes the results for all described native European freshwater fishes and lampreys (hereafter referred to as just freshwater fishes)(vii).”

A review of 531 freshwater fish species across Europe yielded the main finding that:

“Overall, at least 37% of Europe’s freshwater fishes are threatened at a continental scale, and 39% are threatened at the EU 27 level. A further 4% of freshwater fishes are considered Near Threatened. This is one of the highest threat levels of any major taxonomic group assessed to date for Europe. The conservation status of Europe’s eight sturgeon species is particularly worrying: all but one are Critically Endangered (vii)”

In short, freshwater fish are amongst the most vulnerable taxonomic group in Europe, with a number close to extinction. This is a worrying conclusion, and one that calls for rapid and effective freshwater conservation work. The main threats to European freshwater fish were identified as pollution, water abstraction, overfishing, dam construction and the introduction of alien species. The authors call for stronger and more effective political protection for freshwater fish (e.g. through the EU Habitats Directive), and better conservation management for freshwaters (e.g. through the use of Key Biodiversity Areas).

The authors advise that: “In order to improve the conservation status of European freshwater fishes and to reverse their decline, ambitious conservation actions are urgently needed. In particular: ensuring adequate protection and management of key freshwater habitats and of their surrounding areas, drawing up and implementing Species Action Plans for the most threatened species, establishing monitoring and ex-situ programmes, finding appropriate means to limit further alien species introductions, especially by anglers, and revising national and European legislation, adding species identified as threatened where needed. (viii)”

More information:

Seasons Greetings! A Christmas Card Puzzle….

Image: Pilot Visualisation of an Environmental Network, by T. Turnbull, Oxford, Dec 2011.

It’s that time of year again…time for a Christmas card…

The communication and dissemination work (including this blog!) within BioFresh is run by members of the Conservation Governance Lab at The University of Oxford. The Conservation Governance Lab have released a fun seasonal puzzle in the shape of a novel Christmas card. The image above is not – as you may have thought – a Christmas tree or snowflake (although squint and it may well look a little like it…). Instead it shows an interesting environment-related issue which you’re encouraged to guess. Clues are being released through the Lab twitter account: @ConsGovOx.

As the Lab state:

“Step changes in digital technologies are generating vast amounts of environmental data. Capturing and experimenting with ways to analyse this data is creating a new data-driven science that may reveal novel and important insights for conservation governance.”

What environmental network is visualised?

To enter the Christmas Competition: tweet your answer to @ConsGovOx and follow the account for clues.

Leafpack in the Cuisance River (France). Image: Núria Bonada

A new publication by BioFresh partners Dr Paul Jepson and Rob St.John at The University of Oxford argues that freshwater ecosystems should be given more attention by policy makers in order to balance the needs of the many users of freshwater with the need for ecosystem conservation. The article “Going with the flow?: The need for more holistic, data-led freshwater policy” is the environmental lead feature in the most recent edition of Public Service Review: European Science and Policy (14). The article is available as a web page here and as an interactive online magazine (p134) here. The piece also features some beautiful photography by BioFresh scientists Núria Bonada and Sonja Stendara.

The authors argue that: “given that water is a dynamic, transboundary resource with multiple uses, meanings and types of management, freshwater biodiversity conservation is in need of increased attention from policymakers – not only for moral or aesthetic reasons – but also potentially for its role in maintaining and enhancing ecosystem services”.

At the risk of an obvious pun, water is a fluid resource. It is used for energy production, irrigation, drinking water, washing, recreation (the list goes on…). Water underpins and sustains our lives. The article argues that this wide range of uses means that more economically-orientated uses such as irrigation or energy production may overshadow the need for ecosystem conservation for the sake of biodiversity or recreation in policy making.

Given this, the article suggests that there is the need for more holistic, strengthened approaches to freshwater ecosystem policy. However, this holistic, transboundary approach to freshwater policy making will require more detailed and joined up information on the trends, status and distribution of freshwater biodiversity. This is the primary goal of the BioFresh project, which you can find out more about here: freshwaterbiodiversity.eu