Tree of Rivers

Scientists from WWF have developed a new set of tools for planning ‘greener’ human development in the Amazon Basin in South America.

This new animation explains how WWF’s Hydrological Information System – Amazon River Assessment methodology (HIS / ARA) uses scientific data on how this vast rainforest and river system functions to asses if and how development (such as hydropower schemes) might take place along the 100,000 km of freshwater in the biome whilst minimising negative impacts on surrounding ecosystems.

The animation shows how the HIS / ARA project sees the Amazon as an integrated ‘vascular system’ of interconnected ecosystems. The project models ecosystem and hydrological data from the ecosystem scale all the way up to the whole Amazon basin in order to identify priority areas for conservation. This work is intended to show the most crucial freshwater ecosystems in the wider functioning of the Amazon basin, which are likely to be irrevocably degraded by human development, and so help strengthen their conservation and protection.

This map plots the location of barriers – mostly dams – that disrupt the migration and completion of life-cycles of fish in the Danube river system. It was developed to inform the development and implementation of the Danube River Basin Management Plan.

Located in central and eastern Europe the Danube is the world’s most international river basin: four countries – Romania, Hungary, Serbia and Austria – amount for over 50% of the river basin area, but 81 million people in 19 countries share the Danube River Basin.

The development of River Basin Management Plans is one of the key requirements of the EU Water Framework Directive. Prior to the introduction of the WFD in year 2000, the 1994 Danube River Protection Convention established already a legal framework for trans-boundary water management. To support implementation of this convention the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) was created and in year 2000 took on responsibility for coordinating implementation of provisions in the WFD. Given the size and the ecological, social, political and economic complexity of the Danube River Basin this is quite an undertaking!

The publication of the Danube River Basin Management Plan in 2009 was preceded by a range of assessments. Raimund Mair, a technical expert with ICPDR described how hydro-morphological changes to the river system, caused by dams and other structures, were a major issue for technical teams grappling with how to deliver the ‘good ecological status’ objective of the WFD. “The Danube supports a number of long- and mid-distance migratory fish that need to move along the river to their spawning grounds and are barred from doing so by dams”. The Sturgeon and Danube Salmon are the best known examples. Historically sturgeons travelled up to 2000 km from the Black Sea along the river system and have become something of a ‘poster child’ and ‘flagship species’ for the Danube.

Fish Ladder on the Danube. Source: http://pixabay.com/en/fish-ladder-munderkingen-danube-245601/

The purpose of the map of barriers is to identify priorities for investments in fish migration aids at points in the river system that will generate the biggest ecological gain. According to Mr Mair the number of dams is significant, requiring a decade or more to take the necessary measures to restore connectivity. According to the assessments the highest priority but also most outstanding challenge to establish continuity are the so-called ‘Iron Gate’ hydropower dams at the 134 km long Iron Gates Gorge linking Romania and Serbia.

Mr Mair explained how the process of creating the map establishes its conservation policy impact. The ICPDR convenes technical teams involving experts from river management and conservation agencies in the ICPDR member states. “The process of developing methodologies – for instance criteria for prioritising measures at dams – helps to build a shared understanding of the river system, its ecology and the challenges of management, creating the ability to have conservation policy impacts”. This ‘bigger picture’ knowledge in combination with the shared policy vision and agenda of an international technical team empowers national experts to translate the map into action in their respective countries, and to elaborate more detailed prioritisation agendas at national level respectively.

A key task for implementation is to create understanding and support with the owners of the facilities as well as to mobilise the funds to construct the fish passes and other migration aids. These are not cheap, and different countries adopt financing models attuned to national circumstances and opportunities. “In some countries a major share of the funds come from government budgets, and often some form of co-financing arrangement is agreed between government and the company or institution owning and operating the dam. EU funds have also been applied for.” noted Mr Mair. The point here is that it is the combination of the map and supporting technical documents and an international technical committee that creates and legitimates the case for investment in structures that aid fish migration across structural barriers.

Additionally, this map communicates a clear vision to an environmental issue. Conservation NGOs, notably the WWF Danube Carpathians Programme, use their networks, policy access and public profile to convince governments and industry to implement prioritisation agendas for restoring ecological connectivity and mobility in the Danube river system.

In summary, this map in the Global Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas is far more than a 2-dimensional depiction of priority locations for the installation of fish migration aids. It embodies a transnational movement of technical experts working to restore the ecology of one of the world’s greatest river systems.

Dialogue, debate and new horizons for science blogs

Catalonian mountain stream. Image: Nuria Bonada

In Part One of their discussion, Paul Jepson and Rob St. John covered the practicalities and possibilities of running a science blog. In this second, and final instalment, they discuss the role of dialogue and debate in science communication through blogs, and sketch possibilities for future developments in the field.

—

Rob St. John: We’ve talked about different types of blog posts – features, interviews, multimedia content – I’m interested now in what happens when a blog post is published. PLOS science blogs published an article at the end of 2012 entitled ‘Ten Essential Qualities of Science Bloggers’ – which included qualities such as a distinct voice, enthusiasm and an awareness of audience which we’ve covered here. One of the qualities that interested me was ‘to engage in civilised debate’. In a lot of ways, I think this relates to the dialogue and engagement based models of science communication (a good Alice Bell blog on the topic here) that we used to help guide our approach for setting up the blog.

I’ve two questions on this: first, how successful has the blog been in facilitating debate? Second, how does the blog as a focus for debate help us form the communities and networks that you mentioned right at the start of the interview?

Paul Jepson: Given my experience with BioFresh I feel that facilitating on-line debates is one of the real challenges for science blogs – they’re time consuming and require expertise and tact to facilitate and moderate. Discussion flowed when we re-posted Martin Sharman’s 2013 post on ecosystem services on a freshwater related LinkedIn group, which brought a new community into the debate. As we know the blogosphere can be open to some pretty sharp and opinionated comment, which you have to be either think-skinned or experienced (or both) to with.

At the moment my thinking is that science blogs such as ours work well in the sense of traditional media – providing a collection of stories, perspectives, reports and responses that may be discussed in the analogue world – chatting over coffee, on the phone, at meetings – and this is when they help strengthen epistemic communities and networks.

RSJ: So the blog is one node in a set of information, which stimulates debate and information exchange both online (LinkedIn, Twitter etc) and in real life?

PJ: I see them as sitting among a scientific assembly of journals, conferences, workshops, project meetings and so forth. But they offer something new – the ability to connect, provide regular reminders of community and shared interest, and to engage the wider scientific, cultural and recreational interests public audiences in the field..

Screenshot from ‘Water Lives…’ animation (2012)

RSJ: Following on from Martin Sharman’s much discussed post on ecosystem services, I wanted to ask whether you think that a story needs to be controversial in order to find an audience? Can important, but non-headline grabbing stories bring people to the blog and stimulate debate?

PJ: I don’t think a post has to be controversial to be engaging, no. And absolutely, I think there is a public information role for blogs in communicating the stories that don’t grab the headlines elsewhere. One of the pieces that you commissioned about the mayfly’s life cycle (by the Riverflies Partnership scientist Craig Macadam) is our most popular post ever – and I think will continue to be so – because it provides a great answer to a commonly asked search engine query: ‘What is a mayfly?’ and now tops the Google result for that questions.

Leafpack in the Cuisance River (France) Image: Núria Bonada

RSJ: So search engine optimisation is useful in bringing people to the blog. The post has also been listed as an authoritative source on the Wikipedia page for the mayfly.

PJ: I think the potential of building on these posts as interactive information resources on other social platforms is something we haven’t fully explored yet. For instance, the post by Szabolcs Lengyel on wrapping bridges for may fly conservation was eye-opening and fantastic, and these sort of posts could be linked to places on Google Earth and even Google Glass in such a way that when somebody is on the bridge (in this case of the Tisza) or sees the phenomenon in real life, these engaging scientific accounts might pop up.

RSJ: I wanted to bring a set of different people together with the mayfly series to create a set of posts with wide appeal, which I think was pretty successful. On your last point about extending the blog with new technologies, the platforms we use such WordPress do set limits on what we can currently create in terms of interactivity without engaging with programmers. I wanted to ask you what you thought about what’s on the horizon for future blogging and science communication projects?

PJ: In think you a right. In a sense we’ve been exploring the new frontiers of science communication but that frontier is only just opening up with new technology. As the potential of natural language data processing and predictive analytics becomes more widely known I think we are going to see much more integration of blogs and other on-line platforms. The Guardian data blog is interesting to follow in providing pointers, not only for the sort of material that science blogs are likely to carry, but maybe in predicting the fusion of data, narrative and reader preference in the future.

For me, working on the BioFresh blog since 2010 has helped me scope future possibilities and purposes of science communication. I am not entirely sure where things are going, but I am much more aware of what to track and read, who to network with and what to respond to, as a result.

Lilla Fargen, Sweden. Image: Wikipedia

RSJ: I think for me, one of the overarching benefits or values of the blog has been what Sarah Tomlin called ‘an insight into the academic coffee room chatter that the public is not usually privy to’. I like the potential of the blog in profiling and discussing journal articles, research threads, even large EU projects that otherwise go unnoticed.

PJ: In many ways is also all about accountability. Transparency in different forms is become more and more important in maintaining the legitimacy of science in society, and I think science communication work through blogs helps shed light on aspects of big research projects that might otherwise be missed by the public. And now the BioFresh blog is transitioning to the MARS project and the Freshwater Blog. It’s a real strength of these science blogs that they can be passed on and maintained as one project finishes and another one starts. They are a transferable ‘asset’ for science, policy and, I hope, society.

Why run a science blog?

A beautiful photograph of Lake Vendel, Sweden by BioFresh scientist Sonia Stendera

In the coming weeks, this blog will transition to the new Freshwater Blog run by the MARS project. To mark this transition, Paul Jepson and Rob St. John discussed the process of running the BioFresh blog, broadly asking: ‘what is the value of running a science blog?‘.

Paul is the head of the Biodiversity, Conservation and Management MSc course at Oxford University and the leader of the Communication and Dissemination work package with BioFresh. Rob is an environmental writer, and will run the new Freshwater Blog. Paul and Rob set up and edited the BioFresh blog in 2010.

This discussion is split into two parts. Part two will be published on Monday.

—

Rob St. John: I think we should open with a broad question: what’s the value of running a science blog like this one?

Paul Jepson: There’s two answers to this. First, the value for the wider science and policy community and our intended audiences; and second, the value for the people running the blog – the editor and author(s).

On the first point, I think that the BioFresh blog shows the potential of science blogs in strengthening and giving profile to epistemic communities – by which I mean the communities of scientists who help decision-makers to define the problems they face and deliver the policy frameworks for which they are responsible. In our case this community was freshwater scientists and policy-makers delivering the EU biodiversity strategy and directives such as the Water Framework Directive.

On the second point, the value for me was developing my understanding of the practicalities of running a blog, from developing editorial guidelines to translating science and policy into short easy to read pieces which integrate with wider social media ecosystems.

Reflections on water in Europe. Image: Europa JRC

RSJ: I guess there’s also a third main value – that of reaching new, interested audiences with science and policy issues that might not otherwise reach them. When thinking about how the blog is run, one common response from academic and policy making colleagues is that the process of blog writing and commenting is too time-consuming to be practical, and has little benefit for the researcher. Do you think this is the case?

PJ: I’d agree with the time-consuming nature of commenting on posts. We do need to formulate comments carefully because we are operating in an environment where precision and evidence are considered a key quality of a scientist’s work, and the fast paced nature of comment threads may seem a world away from this.

However, the writing side is easier for two reasons. One is that it can be fun and relaxing to write about your work in a popular style and I find this can free me up to think about things in fresh ways. Similarly, as leader of the Biodiversity, Conservation and Management MSc course at Oxford University, I have found that science blogs give students an opportunity to gain experience and skills in science communication and public engagement.

RSJ: Would you agree that developing skills in communication and engagement is an important outcome for modern conservation courses like BCM?

PJ: Yes I do. There seem to be more and more jobs opening up in think tanks and consultancies, and as science-policy advisors and all of these roles need good public engagement skills. I think the style used for writing and then promoting blog posts via social media (for example, Twitter) helps develop skills many employers are increasingly looking for.

RSJ: One of the main values of the blog is as a node on a network of different people loosely connected with freshwater research, conservation and policy. This network also includes wider interest groups: fishermen, aquarium keepers, wild swimmers and the general public.

The blog becomes a place where all sorts of information can be pulled together and put across in a clear, engaging way. I think ideally, it brings different people together to find out and celebrate the value of freshwaters. Based on what we’ve talked about so far, I’m interested in finding out whether your involvement in the blog has influenced your professional practice in any way?

Paul Jepson and Klement Tockner in discussion

PJ: I’m not sure about that. There’s the idea here of working as a boundary scholar across disciplines, which might sound a bit pretentious, but for me blogs embody the idea that there’s no such thing as lone science anymore. But generally I’m seeing that the ecological sciences are needing to embrace technologies and expertise from other disciplines – information engineering, computer science, linguistics, anthropology, social science and so on.

One of the benefits of the blog is that it fits with the idea that new frontiers for science and policy lie in forms of collaboration and interdisciplinarity: blogs creates a virtual space where different groups can share ideas and get a sense of where each other are coming from to work towards common goals.

Screenshot from ‘Water Lives…’ animation (2012)

RSJ: Let’s talk about the practicalities of putting a blog post together. For example, a blog post explaining and analysing a new journal article will usually take me around one or two working days to research, write, edit and fact check before it can be published. It can be done more quickly, but I’m very aware of making sure every piece is accurate and fact checked before publication.

It’s really a case of making sure you can pull out the important messages from a piece of research and then translating these into forms that your audience will be receptive to. How do you manage that process of finding stories to report, then translating them into blog posts?

PJ: You’re right on the science reporting. I think when you and I were running the blog (between 2010-2012), we had a good system of planning a mix of different types of posts, which required different levels of precision and therefore amounts of time to write. For example, I liked doing the interviews with policy makers and scientists. The one with Anne Teller probably took less than 3 hours in total time to complete. All it took was a couple of emails to get Anne on board, then generating a list of questions, tidying up her replies and formatting the piece for publication.

Video interviews are also very quick to do. Again, it’s just a matter of generating a few good questions, and then chatting these through for 10 mins and recording a short Skype video, and then maybe 45 minutes editing the video and writing the accompanying text. The production values of these videos are a bit DIY, but they get the ideas across concisely and engagingly without needing a huge amount of resources.

RSJ: That’s a related question: do you need a lot of resources to put together multimedia material for a science blog?

PJ: No, this is the beauty of computing as a utility. I think all we used was WordPress platform, Skype and some paid add ons for each.

RSJ: So it’s possible to create a range of interesting multimedia with a basic set of computer resources that most academics, students or policy makers will already have available to them such as webcams, coupled with cheap and free software and platforms like WordPress (for creating blogs), Audacity (for editing audio) and Soundcloud (for uploading it), iMovie (for editing video) and Vimeo and YouTube (for uploading it).

In addition to the daily and weekly features and interviews, we put together a few more ambitious projects with high production values such as Water Lives… animation, the BioFresh animation and the Final Symposium video and podcast. What’s the value of more ambitious, often interdisciplinary projects like these?

PJ: A collaborative project such as ‘Water Lives…’ got us and the blog featured on other big blogs such as National Geographic and their social media feeds. Basically, they provided an opportunity to increase reach and readership beyond our ‘normal’ audience networks. I think Will Bibby (blog writer 2012-13) saw another potential, in that these video projects can be re-used over and again in the context of the numerous online events such as World Water Day.

Scientists make excellent photographers! A river in the Rif region (Morocco) by BioFresh scientist Núria Bonada

RSJ: So these more ambitious science communication video projects related to the blog have two important features. First, they have the ability to travel and be picked up by media and audiences that we wouldn’t otherwise reach; and second, they have a longer lifespan and remain relevant and can be used for a variety of other communication initiatives (not least in teaching, conferences, workshops etc) as well as online.

I’d add a third key value, in their creative potential for everyone involved: scientists and policy makers alongside artists and writers. This loops back to what you said at the start of this interview about the blog as a place where people can find fresh expressions of their work outside of the limits of academic writing and presentations. They give an opportunity for everyone to engage with the same material – microscopic diatoms, in the case of ‘Water Lives…’ – in new, creative ways. In terms of engaging audiences with science, I can only see this as a positive thing.

PJ: This chimes with our ongoing discussions about the role of artistic engagements in the generation of novel approaches to research and action in conservation – or any field of academic and policy endeavour (see for example, our artist statements for the Water Lives… project)

—

Part Two will be published on Monday, reflecting on what happens when a blog post is published, how to facilitate and moderate debate, and thinking about new developments in science communication.

Maps in Action: Freshwater Ecoregions of the World

A fundamental task of conservation science is to create planning frameworks that simultaneously render important attributes of nature visible, create the imperative for strategic action, and support the implementation of conservation policy instruments. This map from the Global Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas exemplifies one way this task is realised in practice.

In response to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity substantial funds were committed to the conservation of biodiversity internationally. Two of the world’s leading conservation Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) joined forces to create a global ecoregional planning framework. This set broad scale spatial priorities to guide the field programmes of their organisations as well as others, and to support biodiversity conservation investment decisions by international donors. There are now three dedicated ecoregion ‘maps’: covering terrestrial (2001), marine (2007) and freshwater (2008). Together these maps present regional scale ecosystems at a global level.

The Freshwater Ecoregions of the World (FEOW) map took 10 years to complete and involved coordinating contributions of over 100 scientists worldwide. Co-lead Robin Abell described how its production involved overcoming the challenge of poor species data in regions such as Southeast Asia and much of Africa, pushing taxonomic experts to make their best estimations of where they would expect to find different species and species groups. According to Ms. Abell, “one of the key conceptual challenges was how to align biogeographic patterns of freshwater biodiversity with river basins. River basins are the key unit of freshwater ecosystem policy and management.” Whilst basin topography is a critical factor influencing the patterns of freshwater species distributions, it is not the only one. In many cases it was not possible to align biography and basin (geo-morphology) and biographical consideration took precedent. The down side of emphasizing biogeography is that the species lists compiled for each ecoregion are sometimes not of direct use to managers focused on a particular river basin. The up-side is that it brings freshwater datasets into the sub-discipline of conservation biogeography – the application of biogeographical principles, theories, and analyses, being those concerned with the distributional dynamics of taxa individually and collectively, to problems concerning the conservation of biodiversity.

None-the-less, in 2006 Brazil incorporated freshwater ecoregions as planning units into their National Water Resources Plan – the first such plan for any South American country. This assures that aquatic biodiversity management becomes a strategic consideration for water resource management alongside traditional priorities of hydro-power, navigation, irrigation drinking water and sanitation.

Confluence of the Iguazu and Parana rivers. On the left is Paraguay, on the right Brazil, taken from Argentina Phillip Capper, Wikimedia Commons

Commenting at the time Glauco Freitas, the Nature Conservancy’s Great River Partnership (GRP) manager for the Paraguay-Paraná watershed, described how “from the beginning of our conversations with the Brazilian government about their freshwater management plan, they have been cognizant of the importance of protecting Brazil’s waters not only for the sake of their extraordinary aquatic life, but also to protect sources of water for communities. GRP actions will now be closely linked with the Freshwater Management Plan.” However, in the view of Ms. Abell the real policy impact of the Freshwater Ecoregions map is more fundamental. She describes how “15-20 years ago many in the conservation community weren’t talking about freshwaters. The discussions were either about terrestrial or marine, or about the biodiversity of regions such as Amazonia. The freshwater ecoregion project, along with that of other groups such as the IUCN Freshwater Unit, opened conversations about freshwater biodiversity and its conservation.” These had the effect of “drawing attention to freshwater as a domain of conservation in its own right”. In short, freshwater ecoregions are contributing to a shift in how we frame global biodiversity at the most basic level – from terrestrial & marine, to terrestrial, freshwater & marine.

Special Feature: Maps in Action

Integrating the conservation and management of aquatic organisms into water resource policy is a major challenge. To support policy makers in this effort, freshwater scientists launched the online Global Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas in January 2014.

Integrating the conservation and management of aquatic organisms into water resource policy is a major challenge. To support policy makers in this effort, freshwater scientists launched the online Global Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas in January 2014.

The Atlas currently contains about 30 maps organised into four chapters: freshwater biodiversity, resources and ecosystems, pressures, and conservation & management. It is a dynamic resource that will constantly be up-dated with new maps.

The term ‘atlas’ often evokes a collection of maps designed to foster discovery and learning on a particular topic. However, maps have always been more than representations. Many are also powerful decision support tools. Increasingly, the maps we see are spatial representations of geo-located data sets or assemblies of data sets, and for scientists and policy makers they draw attention to the availability of data that can be put to use.

This short series of articles aims to explore the active role of maps at the interface of science and policy.

- Freshwater Ecoregions

- Situation and prioritisation of barriers along the Danube and its tributaries for restoration of longitudinal connectivity

- The European Fish Index

- Key Freshwater Biodiversity Areas and protected area planning

Together these Maps in Action articles remind us that maps are a form of standard that enables coordinated action between nations and across scale. They foreground the role of maps in issue framing, the building of policy communities and shared understandings across scales, for prioritising policy implementation and legitimating the case for investments in actions to conserve, manage and restore hydrological systems.

The Global Freshwater Biodiversity Atlas is a major achievement of the BioFresh project because it brings together a unique overview of the status of interactions between freshwater biodiversity science and policy.

Meet the MARS Team: Laurence Carvalho

A swan taking off from Loch Leven, Scotland. Image: L Carvalho.

This week we continue our ‘Meet the Team‘ series with an interview with MARS researcher Laurence Carvalho.

This week we continue our ‘Meet the Team‘ series with an interview with MARS researcher Laurence Carvalho.

Laurence is a freshwater ecologist at the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology in Edinburgh, Scotland. He is particularly known for his work on the impacts of eutrophication and climate change on lakes.

He has previously worked on European Commission projects such as WISER, REBECCA and Eurolimpacs, and helped develop a phytoplankton classification tool for UK lakes for the Water Framework Directive.

1. What is the focus of your work for MARS?

I am leading the “synthesis” Work Package in MARS, which aims to synthesise the results from experiments, observations and modelling carried out in the project.

The aim is to compare how stressors interact across different spatial scales from individual water bodies, across river basins and all the way up to the European scale. The work also aims to use this synthesis to identify diagnostic indicators and deliver recommendations for improved Integrated River Basin Management across Europe.

More personally, I hope to contribute to work examining the response of lake algal blooms to the combined effects of nutrients and extreme climatic events. I plan to look at this using a long-term dataset from Loch Leven in Scotland and a large-scale dataset from lakes across Europe.

Loch Leven, Scotland. Image: L Carvalho

2. Why is your work important?

Freshwaters provide society with so many benefits, not just water for drinking and agriculture. Many of these benefits, such as fishing, recreation and tourism, rely on diverse, healthy ecosystems and good water quality.

It is important that we better understand the linkages between ecosystem health and human health and well-being, as this should ensure greater public and political support to manage this resource more sustainably in the future.

In addition to these benefits to humans, the intrinsic value of freshwaters in supporting a rich biodiversity – whether that is birds, fish or frogs – is also fundamentally important.

The amazing world of algae: the cyanobacteria that gave our planet oxygen. Image: L Carvalho.

3. What are the key challenges for freshwater management in Europe?

Better management of floods and droughts given increasing climate extremes is probably the key challenge. Ideally finding more nature-based solutions to these challenges, such as working with society to create more naturally functioning floodplains, rather looking at the river or the lake as the problem.

As well as floods and droughts, given that a high proportion of freshwaters in Europe that are in less than good status and there is an ongoing loss of freshwater biodiversity, another key challenge is working out what so-called “sustainable exploitation” really looks like and putting in place better integrated policies and management to achieve it.

If done carefully, incorporating concepts of “ecosystem services” into policy and management should help with this.

Working at the European Commission at Ispra, Italy also allowed for frequent “sampling” trips to Lago Maggiore… Image: L Carvalho

4. Tell us about a memorable experience in your career.

Surveying rare aquatic plants in the amazing watery landscape of North Uist off the west coast of Scotland is right up there for breath-taking scenery and life’s simple pleasures. It matches lake coring in the deserts of Inner Mongolia, working for a year at the European Commission in Italy and playing water polo in Lake Balaton with friends and colleagues at the Shallow Lakes meeting in Hungary.

Water Polo in Lake Balaton, Hungary at the Shallow Lakes conference 2002. Image: L Carvalho.

In fact every Shallow Lakes conference is inspiring in terms of work and play, so I can predict my next memorable experience will be at their next meeting in Turkey this October!

5. What inspired you to become a scientist?

Probably a local priest who dismissed the theory of evolution! This was about the same time as David Attenborough’s fantastic BBC television series “Life on Earth” which described the rich evidence behind this wonderful process in all its glory.

A day off work in Italy well spent! Image: L Carvalho.

6. What are your plans and ambitions for your future scientific work?

There’s still lots to learn about algae and other microbes – their fundamental role in providing us with clean water and a stable atmosphere offers plenty for the future! But I am very keen to work more with people outside my discipline, with social scientists and environmental economists, to really deliver a greater understanding of the value of restoring the health of our freshwaters.

—

You can read more about Laurence’s work at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology website, and follow him on Twitter @LacLaurence.

River Ribble, Lancashire. Image: RSJ

Worldwide efforts to conserve river ecosystems are failing, and new approaches for stronger conservation planning are required. This is the underlying context of a new editorial ‘Rebalancing the philosophy of river conservation’ by Mars scientist Steve Ormerod in Aquatic Conservation Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. Ormerod suggests that the ecosystem service approach can offer a valuable addition to current river conservation strategies, potentially providing convincing new arguments to help halt freshwater biodiversity loss.

Growing human populations are putting increasing pressure on freshwater ecosystems globally: altering and fragmenting river flows; abstracting water for agriculture, sanitation and drinking; and releasing unprecedented amounts of pollutants into freshwaters. As David Strayer and David Dudgeon outlined in a 2010 paper, despite freshwater ecosystems occupying less than 1% of the Earth’s surface, they support around 10% of all known global species.

As well as being hotspots for biodiversity, freshwaters are often focal points for human development, the negative effects of which – pollution, overfishing, flow fragmentation – mean that freshwater species are more threatened than those in marine or land environments. Many key threats to freshwater ecosystems are generated at the river catchment scale, where the interactions (and potential intensifications) of ecological stresses caused by pollutants from agricultural and urban development are not fully understood (as Ormerod previously wrote in 2010).

Industrial River Ribble, Lancashire. Image: Blog Preston

However, the picture isn’t necessarily bleak. In this new editorial, Ormerod argues that the ecosystem services approach to managing nature – where the benefits provided by an ecosystem are valued in explicitly human terms rather than on an ethical basis – has the potential to strengthen and reinvigorate river conservation management.

The basis of the ecosystem service argument is that well-functioning ecosystems are fundamental to human livelihoods. However, many ecosystem services – food and fuel production, flood regulation and water supply to name a few – are undervalued, or regarded as ‘public goods’, by the models that structure global economic development.

In this context, ecosystem services are framed by some conservationists as a powerful means of convincing people, institutions and governments of the value of the natural world under the logic of economic and social self-interest. In other words, I might be motivated to conserve nature, not necessarily because of any ethical arguments, but because of the benefits nature provides to me and my livelihood. As a result, the approach has gained traction to become one of the dominant themes of conservation policy in recent years.

Ormerod suggests that this ‘enlightened self-interest’ is likely to provide a stronger basis for both citizens and policy makers to become more motivated to conserve rivers. This approach may have the potential to provide common ground for individuals and institutions across catchments and river basins to collaborate in planning conservation, a particularly valuable asset given the numerous competing concerns of stakeholders along a river’s course.

Ormerod’s argument is that the ecosystem service approach can sit as an addition to existing river conservation approaches – broadly described as ‘protect the best, restore the rest‘ – where healthy, diverse ecosystems are conserved, and those that are polluted or degraded are restored as far as possible. This existing approach is ingrained in European policies such as the Habitats Directive and Water Framework Directive.

New approaches to conservation policy? Image: Europa JRC

Water supply from river ecosystems is undoubtedly one of most indispensable ecosystem services. Given that rivers are hotspots for biodiversity, human development and ecosystem services, if the ecosystem service approach has the potential to strengthen conservation planning anywhere, then river ecosystems seem a likely candidate for success.

According to a 2011 paper Ormerod co-authored with Edward Maltby for the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (link opens as zipped download), evidence is emerging from rivers and their catchments that conservation priorities based on biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision may not be mutually exclusive.

In other words, the ecosystem service approach may help strengthen conservation efforts by providing convincing arguments for a range of users, land owners and policy makers to make decisions which not only serve their social and economic self-interest, but also help avert biodiversity loss.

Ormerod’s point is that the approach has been under-applied to freshwater conservation, and given the wide range of important ecosystem services that rivers provide, may well help provide new and convincing arguments for their conservation. New tools in a toolkit of strategies to help halt biodiversity loss.

Zebra mussels. Image: Wikipedia

However, there are numerous considerations to be addressed. The ecosystem service approach to conserving nature has drawn criticism on both practical and philosophical grounds. It is argued that the approach supports the conservation of those species that provide notable and financial benefits to humans and ignores those that do not. As Kent Redford and Bill Adams pointed out in a 2009 Conservation Biology editorial, zebra mussels are far better at filtering pollutants out of water than any ‘native’ UK species – should we therefore prioritise their (non-native, invasive) populations for the ecosystem services they provide?

Similarly, if we value nature only for its potential utilitarian worth, are we not missing the reasons – ethics, curiosity, beauty, wonder – why most people are motivated to care about and conserve the natural world? Can species and ecosystems really be reduced and appropriately catalogued into commodities? Can they be accurately mapped, and what about the effects of geographical scale on their provision? Does their provision benefit everyone across society, or are there those who remain marginalised? How will planning for ecosystem services be affected by climate change?

These are debates to continue more fully in another post. For now, we’d be interested to hear your thoughts, comments and feedback on Steve’s paper.

Fundamentally, there are (at least) two major questions arising from the paper. First, how can the ecosystem service approach help strengthen freshwater conservation? Second, can the priorities of ecosystem service based approaches to river conservation be integrated and ‘rebalanced’ with existing biodiversity-orientated approaches? If so, how?

Is there life on MARS?

Yellowknife Bay in the Gale Crater on Mars, where evidence of an ancient freshwater lake has been found. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

Is there life on Mars?

This line from a David Bowie song has become a recurring pun as new MARS project (‘Managing Aquatic ecosystems and water Resources under multiple Stress’) takes shape. Recent findings from NASA’s Curiosity Rover mission to Mars have suggested that a large freshwater lake, potentially capable of supporting life, existed on the planet around 3.5 billion years ago – around the time that life began to emerge on Earth. So, as the MARS project works on Earth’s freshwaters, the Curiosity Rover is uncovering evidence of freshwater on Mars.

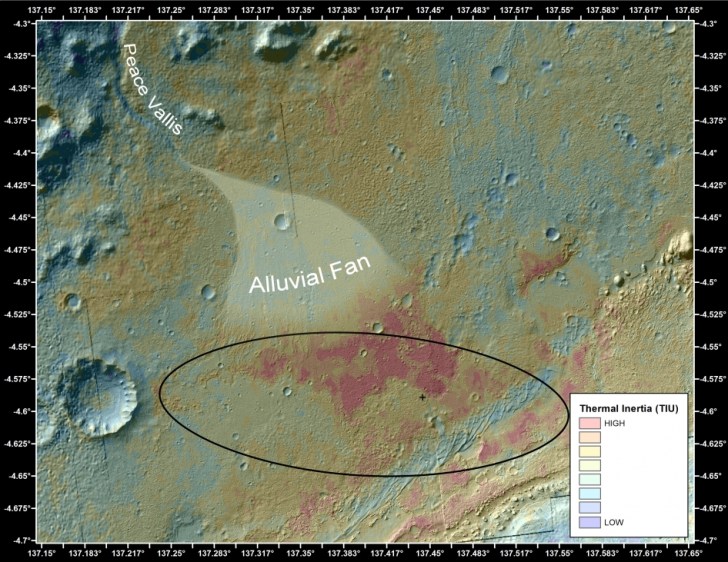

A special issue of Science published in January 2014 describes how the Curiosity Rover drilled two mudstone sediments in the 96 mile wide Gale Crater where it landed in August 2012 (you can follow the Rover using the New York Times’ tracker). In September 2012, Curiosity found remnants of a gravel streambed and alluvial fan at the northern end of the crater – evidence of flowing water, again around 3.5 billion years ago.

Alluvial fan in the Gale Crater – a sign of ancient flowing water. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

The mudstone samples, taken at a location in the crater with unusually light-coloured and fine sedimentary rocks named Yellowknife Bay, contained smectite clay minerals with a chemical composition indicating they formed underwater. The presence of these clay minerals suggests that there was a calm body of water present in the crater around 3.5 billion years ago, which could have persisted for hundreds of thousands of years. The small clay particles would have sunk into sediment at the bottom of the lake and been compressed and cemented into rock over time.

Analysis of the rock also found chemical elements which were key to the formation of life on Earth – including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulphur, nitrogen and phosphorous – and evidence the freshwater was likely to have a low salinity and neutral pH. As Dr. John Grotzinger, project scientist on the Curiosity mission from California Institute of Technology said in a New York Times interview, “The whole thing just seems extremely Earthlike”.

Curiosity Rover at Gale Crater. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

Does this mean that Mars may have supported freshwater life, billions of years ago? As Professor Sanjeev Gupta, a member of NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory from Imperial College London states, there’s still much work to be done in finding definite signs of life:

“It is important to note that we have not found signs of ancient life on Mars. What we have found is that Gale Crater was able to sustain a lake on its surface at least once in its ancient past that may have been favourable for microbial life, billions of years ago. This is a huge positive step for the exploration of Mars. It is exciting to think that billions of years ago, ancient microbial life may have existed in the lake’s calm waters, converting a rich array of elements into energy. The next phase of the mission, where we will be exploring more rocky outcrops on the crater’s surface, could hold the key whether life did exist on the red planet.”

As on Earth, such long-term environmental records indicate the climatic and ecological conditions and stresses that would have shaped any freshwater life, in this case pointing towards a wetter, warmer climate on Mars around 3.5 billion years ago. Researchers from the Mars Science Laboratory suggest that the conditions would have been ideal for simple microbial life such as chemolithoautotrophs to thrive in. These simple organisms are found on Earth in caves, hydrothermal vents and deep groundwater, and gain energy from compounds produced in geological weathering (‘lithos’ (rock) and ‘troph’ (consumer) can be read as ‘rock-eaters’).

Artists impression of the Curiosity Rover. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Malin Space Science Systems

However, in his introduction to the Science issue, Dr Grotzinger points out that finding evidence of such ancient microbial life on Earth was a formidable challenge, proven through the discovery of microfossils preserved in silica 100 years after Darwin’s theory of evolution. A key task now for the mission is to find rocks and sediment where organic material from the ancient microbes may have been preserved.

If this preserved material is found, it will not only provide proof that life once existed on Mars, but it is also likely to yield insights for understanding how life developed in response to environmental stresses on Earth. We’ll keep an eye on Curiosity’s exploration of these ancient, high-stress Martian freshwater environments as research continues.

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Beavers, ecological stress and river restoration

In February 2014 a family of wild beavers were photographed on the River Otter in Devon, South West England by a retired ecologist. The animals are believed to be the first evidence of populations living and breeding outside captivity in England for over 400 years.

In February 2014 a family of wild beavers were photographed on the River Otter in Devon, South West England by a retired ecologist. The animals are believed to be the first evidence of populations living and breeding outside captivity in England for over 400 years.

Their (re)discovery prompts a number of questions for the form and function of British freshwaters. What impact will the beavers return have on freshwater ecosystems and human livelihoods? What reference conditions do we use to monitor and assess restoration and reintroductions?

How can the new ecological stresses and processes caused by beavers be managed in such environmental restoration, if at all? These questions are central to the MARS project’s wider research on stress and environmental restoration.

The Eurasian beaver in the UK

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) was once common across Britain, a fundamental link in many freshwater ecosystems. Populations were hunted to extinction in the 16th century for pelt, meat and the medicinal properties of a secretion ‘castoreum’, used to variously treat headaches, fever and ‘hysteria’.

Under the European Union’s Habitat Directive, governments are required to consider the reintroduction of extinct native species such as the beaver (although the concept of what we term ‘native’ often proves tricky to tie down). As a result, there is increased debate in Britain over whether beavers should be reintroduced, perhaps most prominently shown by the experimental Scottish Beaver Trial at Knapdale, South West Scotland.

Keystone species and ecosystem engineers

Beavers are termed ‘keystone species’ by ecologists because their presence is likely to significantly affect the form and function of the ecosystems in which they live. By damming rivers, beavers are ‘ecosystem engineers’, holding back silt (which can increase water quality), creating large, slow pools in rivers and wetland areas on the banks, which in turn provide new habitat for other plants and animals.

Beavers and flooding?

Beaver dam in Lithuania (Image: Wikipedia)

This regulation in river flow may also help reduce flooding and bankside erosion downstream. Following major floods in January 2014 (see our piece on the subject), Marina Pacheco, the chief executive of the UK Mammal Society, recommended that the UK Government promote beaver reintroductions as a means of reducing flood risk in the future, stating:

“Restoring the beaver to Britain’s rivers would bring huge benefits in terms of flood alleviation. These unpaid river engineers would quickly re-establish more natural systems that retain water behind multiple small dams across tributaries and side-streams. As a consequence the severity of flooding further downstream would be greatly reduced, at no cost to the taxpayer.”

By felling and coppicing bankside trees, beavers may create a more open, diverse riverside ecosystems, which support an array of new growth and ground vegetation such as wild flowers.

Experimental trials in Devon

Early reports from experimental trial populations of beavers undertaken by the Wildlife Trust, Devon – where a pair of animals to a small woodland enclosure – show that over a two year period the beavers acted as ‘ecosystem engineers’, opening and diversifying the woodland, creating a set of ponds which store water (potentially reducing flooding downstream) and provide new habitat for other plants and animals.

‘Wild’ beavers on the River Tay

Mother and kit on Tayside (Image: Ray Scott)

However, this process may not necessarily be positive. In 2012, it was revealed that dozens of beavers had escaped from private collections across southern Scotland and had colonised the River Tay in Perthshire. A Royal Zoological Society report from 2012 suggests that there may be as many as 140 animals living along the Tay valley.

A decision by Scottish Natural Heritage not to trap the ‘feral’ animals (as quoted in the Daily Telegraph) sparked outcry from angling groups concerned about the beaver’s presence on populations of migratory fish such as salmon, and from farmers concerned about loss of land and woodland due to tree felling and dam building.

Reintroductions and restoration: what reference conditions?

The reintroduction of plants and (particularly) animals to environments from which they once went extinct is a process fraught with numerous practical and conceptual considerations. Practically, beavers have not existed in Britain for around 500 years, and freshwater ecosystems have developed in their absence over this period. This means that whilst beavers might be considered ‘native’ to Britain, their reintroduction potentially poses new stresses to the ecosystems to which they return.

Ecological reference conditions and the Water Framework Directive

Fish pass on the River Otter in Devon – what is a natural ecosystem here? (Image: Wikipedia)

A journal article “The European reference condition concept: A scientific and technical approach to identify minimally-impacted river ecosystems” published by Isabel Pardo and colleagues in Science of the Total Environment in 2012, and co-authored by MARS partner Sebastian Birk, discusses how ecological reference conditions for the restoration of ‘good status’ in rivers are set.

One of the major challenges for the Water Framework Directive – Europe’s most important policy document on freshwater health and conservation – has been to find common approaches across different countries in defining what reference conditions should be set as targets for freshwater restoration.

Given extensive human alteration of the natural world, coupled with species introductions, migrations and extinctions, selecting a set point in time or ecosystem state as a target for restoration is likely to be problematic.

The Water Framework Directive addresses this variability by stating that ‘good status’ can be defined by geographical characteristics and location. So for example, reference conditions would be set differently for a Scandinavian mountain stream compared to a lowland river in Germany.

Setting criteria for reference sites, stress and ‘ecological thresholds’

Reflecting on restoration (Image: Per Harald Olsen)

The journal article seeks to establish levels of pressure (or stress) on freshwater ecosystems at reference sites with ‘acceptable’ or ‘good’ ecological status. The paper outlines a set of criteria that the authors see as crucial for identifying reference sites, including: pollution, water abstraction, surrounding land-use and alien species.

A key concept here is ‘ecological thresholds’, which describe points where an ecosystem may significantly change form, processes and function in response to external factors such as stress.

I spoke to MARS member and article co-author Sebastian Birk about the challenges reintroduced species such as beavers pose to setting appropriate reference conditions:

“The return of the beaver to our rivers was not really anticipated when we defined the near-natural conditions. Stream impoundments are usually man-made and are thus penalized when assessing the ecological status. The activities of the beaver, however, indicate high status conditions. This may require some rethinking among water managers as well as farmers and anglers. Especially when the riparian zones along our rivers are enhanced, creating a suitable habitat for the beaver … “

Questions for restoration

The case of beaver reintroduction provides a set of challenges to this process of setting ecological reference conditions. The animals are considered ‘native’ to Britain, yet their reintroduction has been shown to significantly alter the ecosystems in which they live and ‘engineer’.

In the case of the Devon beaver trial, the ecosystem passed a threshold from woodland with a small stream, to a more open, diverse habitat with a number of ponds and marshes within two years of the reintroduction of a pair of beavers.

In a sense, beavers bring new stresses to ecosystems that have developed in their absence over recent centuries. Despite the Pardo et al 2012 paper outlining a set of quantitative criteria for ‘natural’ reference conditions for freshwater ecosystems, it could argued that, due to the endlessly altered (and altering) environment, any definitions of ‘naturalness’ are essentially subjective.

In the case of the beaver in Britain, what choices do we make over the form and function of the freshwater environments that we want to live with and enjoy? If beaver populations continue to slowly grow across Britain, how will what we define as ‘natural’ in our rivers and lakes change, if at all?