MERLIN Podcast EP.12 – How nature-based solutions can support people and nature in freshwater restoration

Harnessing the potential of natural processes in freshwater restoration can create significant ecological, social and economic benefits, according to a major new report.

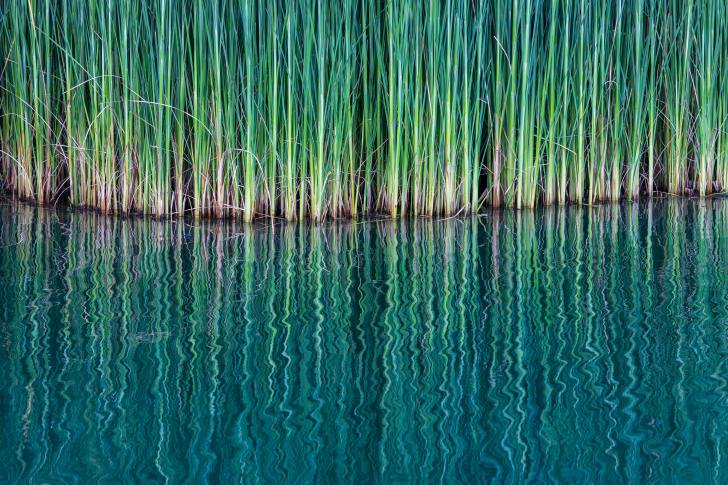

Researchers from the MERLIN project analysed restoration monitoring data from eighteen rivers, streams and wetlands across Europe to assess the impacts of so-called ‘nature-based solutions’ on the environment and society. Such approaches aim to help amplify natural processes to benefit both people and nature. For example, a healthy wetland can help filter water pollution and buffer floodwaters, whilst planting so-called ‘riparian zones’ of trees and other vegetation along river banks can help provide valuable biodiversity habitat, keep water bodies cool, and lock up carbon to help mitigate climate change.

The new report explores the impacts of a diverse range of European freshwater restoration strategies using nature-based solutions. These include peatland rewetting, beaver reintroduction, floodplain restoration and reconnection across a variety of landscapes. The results show that such restoration approaches can generate significant benefits for nature and society. In particular, many of the impacts support the goals of the European Green Deal, which aims to support climate neutrality, sustainable economies and healthy, diverse ecosystems across the continent.

In this podcast, we hear from two MERLIN researchers behind the new report: Laura Pott from the University of Duisburg-Essen, and Axel Schwerk from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences. Laura and Axel cover a range of topics including how to monitor the impacts of nature-based solutions in complex landscapes across Europe, the importance of engaging stakeholder groups around an ecosystem, and the value of Theory of Change approaches in helping map how a restored landscape might develop over time.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

///

A guest blog by Zeb Hogan and Monni Böhm

What do Lake sturgeon, European eel, and Atlantic salmon have in common? They are all fishes that migrate – at least for part of their life – in freshwater systems. These migrations can take vary in length from tens to thousands of kilometres, but are often predictable and cyclical depending on the species’ ecology and environmental cues.

Some species – like the European eel – migrate between freshwater and marine environments to complete their life cycle, other species remain exclusively in freshwater. Many of these freshwater migratory fishes are also vitally important to food security, cultural identity, and livelihoods of Indigenous and rural communities around the world.

Freshwater migratory fishes are also in trouble. Monitored populations of migratory freshwater fish species have declined by 80% in the last fifty years. A prominent threat to freshwater migratory fishes is the loss of connectivity. Globally, only 37% of rivers longer than 1,000 km remain free-flowing, and key biodiversity hotspots such as the Amazon, Mekong, and Congo basins are increasingly subject to hydropower expansion.

In terms of conservation policy, the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), – sometimes referred to as the Bonn Convention – provides a global platform for the conservation and sustainable use of migratory animals and their habitats. It lays the legal foundation for internationally coordinated conservation measures throughout a species’ migratory range.

To aid the conservation of migratory freshwater fishes, a group of leading scientists, conservationists, and policy experts from five continents recently met at the University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe to discuss latest progress in migratory fish work, develop outputs that are usable and impactful for parties to the CMS, and to further develop a Swimways concept – akin to flyways designated for migratory birds.

The meeting was hosted by the Tahoe Institute for Global Sustainability and supported by PlusFish Philanthropy, and produced a set of tangible outcomes that will directly inform global conservation efforts, including preparations for the United Nations Convention on Migratory Species Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Brazil in 2026.

Key achievements included the identification of migratory freshwater fish species that meet the criteria for CMS listing, and further development of a designation of globally significant migration corridors, such as the Danube in Europe, the Mekong in Southeast Asia and the Mississippi river in North America, amongst others.

Participants also committed to several coordinated outputs in the near future, all of which will shape how we better conserve freshwater migratory fishes. These include a report to CMS and COP15; a peer-reviewed scientific paper on freshwater fish migrations; a public-facing global database of migratory freshwater fish for use in conservation planning and research; an analysis of challenges and opportunities in engaging with international policy frameworks; IUCN Green Status assessments of high profile freshwater migratory species; and a suite of educational and outreach materials designed to raise awareness of freshwater biodiversity.

“These are not symbolic conversations—we’re generating the data, strategies, and commitments that will shape global policy,” says Dr. Zeb Hogan, aquatic ecologist and workshop organiser with the University’s College of Science. “The outcomes of this meeting will directly inform global efforts to protect migratory fish populations and restore connectivity in rivers around the world.”

The workshop brought together experts from the UN CMS Secretariat, World Wildlife Fund, IUCN Species Survival Commission, IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, the Global Center for Species Survival at the Indianapolis Zoo, Shedd Aquarium, Cornell University, University of Tennessee, the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, alongside faculty and students from the University of Nevada, Reno.

“This gathering showcased the University of Nevada, Reno’s growing leadership in freshwater biodiversity and environmental sustainability,” says Melanie Virtue, Head of the Aquatic Species Team at the CMS Secretariat. “The UNR Lake Tahoe campus, located on the shores of one of the world’s most iconic lakes, is acting as a global hub for science-informed policy and local-to-global conservation action.”

///

Learn more about the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities: tiny freshwater insect is the ‘loudest animal on Earth’

If you’re a long-time follower of the Freshwater Blog, you might remember our Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities project from more than a decade ago. That website has since washed away down the rivers of time, but we thought it was the right moment to showcase our collection of curious freshwater plants and animals again. So keep your eyes peeled over the coming months as we dust off the Cabinet and celebrate the wonderful world of freshwater life!

///

This month’s entry into the Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities is the lesser water boatman – Micronecta scholtzi – a common European freshwater bug that produces a peculiar courtship song by rubbing its penis along its abdomen, a sound which reaches an incredible 99.2 db! That’s a sound level equivalent to sitting in the front row of an orchestral concert, or standing close to a passing train!

As Dr James Windmill at the University of Strathclyde – a lead researcher on the June 2011 study “So Small, So Loud: Extremely High Sound Pressure Level from a Pygmy Aquatic Insect” – describes, “Remarkably, even though 99% of sound is lost when transferring from water to air, the song is so loud that a person walking along the bank can actually hear these tiny creatures singing from the bottom of the river.”

Micronecta means “small swimmer”, and their sound, used by tiny (2mm) males to attract mates, is produced by rubbing its ribbed penis across its abdomen, in a process called stridulation. In the lesser water boatmen the area used for stridulation is only about 50 micrometres across, roughly the width of a human hair.

This stridulation process is similar to that used by grasshoppers and crickets to produce their idiosynchratic chirps and chirrups. Dr Windmill continues, “If you scale the sound level they produce against their body size, Micronecta scholtzi are without doubt the loudest animals on Earth.”

The loudest human shout ever recorded is 129db by British teaching assistant Jill Drake in 2000. Sperm whales have been recorded emitting sounds reaching an incredible 236db, a cacophony required to communicate across vast, turbulent oceanic distances. Decibels are a measure of the intensity or ‘loudness’ of a sound, measured on a logarithmic scale. This means that for every increase of 10 decibels, there is a 10 fold increase in sound energy.

By comparison, a normal human conversation is generally measured at around 60db. Incredibly, at 99.2db, the sound made by the lesser water boatman is almost 10,000 times more powerful – akin to a car horn, power tool or passing train.

The researchers say their findings demonstrate how aquatic animals such as the lesser water boatman have evolved to be able to communicate in underwater environments. In this case, they highlight how their loud stridulations help the male insects to find a mate.

This remarkable little bug shows that remarkable creatures often live in the most everyday freshwater environments. So next time you’re walking along your favourite river or lake, stop for a moment to listen – you may be surprised what you can hear!

Mapping the value of freshwater restoration

We live in an age of ecosystem restoration. Across the world, communities and policy makers are seeking to help guide degraded or destroyed ecosystems back to health, whilst protecting those that remain intact.

Major initiatives like the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration – which runs from 2021–2030 – highlight the vital role restoration plays in supporting both people and nature. As the UN states, “Healthier ecosystems, with richer biodiversity, yield greater benefits such as more fertile soils, bigger yields of timber and fish, and larger stores of greenhouse gases.”

The benefits that the restoration of global ecosystems could generate are significant. The UN estimates that the restoration of 350 million hectares of degraded terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems by 2030 could generate US$9 trillion in ecosystem services and remove 13 to 26 gigatons of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

Crucially, it is estimated that the economic benefits of these interventions are more than nine times the cost of investment, whereas inaction is at least three times the cost of ecosystem restoration. In other words – as we’ve explored on this blog and in podcasts – the economic argument for ecosystem restoration is increasingly strong.

Ecosystem services and restoration

But how can these benefits best be quantified? The ecosystem service concept has been used for over twenty years to calculate the benefits that people obtain from ecosystems, and underpins many contemporary arguments for restoration action.

Published in 2005, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment identified four categories of ecosystem service. Provisioning services are the products obtained from ecosystems, such as food and raw materials. Regulating services are the benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes, such as the water purification and carbon sequestration.

Supporting services are the processes which allow an ecosystem to function, such as nutrient cycling and habitat provision. Finally, cultural services are the recreational, spiritual, historical and artistic values that ecosystems offer to people.

How does freshwater restoration affect ecosystem services?

In recent years, this approach to valuing ecosystems has influenced the development of nature-based solutions approaches which seek to harness natural processes to help benefit both nature and society.

Ecosystem services and nature-based solutions are both tools to provide decision makers with clear, quantifiable evidence for the significant value of healthy, diverse ecosystems. A key task for environmentalists, then, is to continue to strengthen this evidence to help showcase the vital role flourishing ecosystems play in scaffolding our daily lives.

In this context, a new study explores how freshwater restoration using nature-based solutions affects how waterbodies can provide ecosystem services to people. A team of researchers from the MERLIN project compiled evidence on restoration measures implemented across Europe and asked experts to help assess their value and effectiveness through a Delphi survey.

Mapping the benefits of ecosystem restoration

Writing in the Restoration Ecology journal, the authors identify how many freshwater restoration measures enhance multiple ecosystem services simultaneously. River restoration measures including restoring natural flow, channel structure, and habitat complexity are shown to be particularly effective at generating multiple ecosystem services.

The study highlights how freshwater ecosystem recovery has significantly increased biodiversity, water purification and climate regulation at sites across the world. The authors write that such ‘multifunctionality’ of outcomes “shows that biodiversity-focused actions can also enhance multiple ecosystem services, aligning with broader restoration goals.” However, they caution that such outcomes often vary by context and measure.

On the other hand, the study finds that the ecosystem services delivered by peatland restoration are underexplored, particularly beyond their effects on climate regulation. The authors highlight the need for future research in this area.

The researchers also identify that restoration approaches specifically targeting water pollution are less successful at delivering multiple ecosystem services. As a result, they highlight “the need for integrated approaches combining water quality improvements, hydrological restoration, and vegetation recovery to deliver wider ecosystem service gains.”

Provisioning services benefit the least from ecosystem restoration across both rivers and peatlands, the researchers state. In particular, the effects of restoration on agricultural output were mixed, with some large-scale measures reducing productising in intensively farmed areas.

This finding highlights the difficulties of balancing ecological, social and economic priorities in mainstreaming restoration into daily life, both across Europe and globally.

“We’ve all known it’s a black box – how exactly freshwater restoration measures translate into ecosystem service gains,” explains lead author Sebastian Birk. “With this paper, we finally cracked it open a bit. By carefully listing what’s done on the ground and tying it to semi-quantified effects, we’re one step closer to making that connection visible. There’s still a long way to go – and the need for solid fieldwork – but the door’s open now.”

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Harnessing the potential of natural processes in freshwater restoration can create significant ecological, social and economic benefits, according to a major new report.

Researchers from the EU MERLIN project analysed restoration monitoring data from eighteen rivers, streams and wetlands across Europe to assess the impacts of so-called ‘nature-based solutions’ on the environment and society.

Such approaches aim to help amplify natural processes to benefit both people and nature. For example, a healthy wetland can help filter water pollution and buffer floodwaters, whilst planting so-called ‘riparian zones’ of trees and other vegetation along river banks can help provide valuable biodiversity habitat, keep water bodies cool, and lock up carbon to help mitigate climate change.

The new report explores the impacts of a diverse range of European freshwater restoration strategies using nature-based solutions. These include peatland rewetting, beaver reintroduction, floodplain restoration and reconnection across a variety of landscapes.

The results show that such restoration approaches can generate significant benefits for nature and society. In particular, many of the impacts support the goals of the European Green Deal, which aims to support climate neutrality, sustainable economies and healthy, diverse ecosystems across the continent.

In this context, MERLIN researchers found that using nature-based solutions in freshwater restoration can help boost climate resilience and biodiversity gains, whilst also delivering social and economic benefits such as sustainable job creation and improved social wellbeing.

Rewetting the Tisza floodplains

Floodplain restoration around the Tisza River in Hungary offers a fascinating window into these dynamics. Restoration of the floodplains around the village of Nagykörű in middle of the river’s catchment began in 2001. Prior to this the Tisza had been highly modified by concrete flood walls which cut the river off from its floodplains.

Biodiversity has flourished since the river has been encouraged to return to its natural rhythms by spilling over the reconnected floodplains in times of high water flows. Insects and spiders populations have boomed, whilst rare fish species such as the spined loach and European weatherfish use the flooded meadow habitat as spawning grounds.

Breeding populations of frogs and toads have also grown alongside those of water birds such as mute swans. This lively landscape has become the focus of new nature walks for people around the area.

The reconnected floodplains have also become a carbon sink, with the flourishing vegetation locking up greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Similarly, the flood and drought resilience of the floodplains has increased, in part due to the installation of a sluice which allows environmental managers to control the flows of water across them.

The Tisza River restoration also shows the trade-offs with other land uses inherent in nature-based solutions approaches. Floodplain rewetting here required a 66% reduction in agricultural land area around the river.

Despite this significant loss in agricultural land, the MERLIN report suggests that local communities are in favour of restoration due to its support for more sustainable agricultural practices, and the broader biodiversity benefits it generates.

Lessons for freshwater restoration and policy

The study has two key lessons for freshwater restoration in Europe. First, it provides clear evidence that nature-based solutions approaches can provide significant environmental and social benefits, whilst supporting sustainable economic development and contributing to the goals of the European Green Deal.

Second, it highlights the importance of detailed monitoring programmes that capture the nuanced impacts of nature-based solutions in freshwater restoration. The study shows that whilst nature-based solutions can provide many co-benefits for nature and people, it also highlights the trade-offs and tensions over land use that may arise.

Monitoring these dynamics is crucial to be able to make positive and adaptive decisions about freshwater restoration projects as we move into an increasingly pressurised and uncertain climate emergency future.

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Beavers create diverse new habitats in stream ecosystems which significantly boost biodiversity, according to a new study.

Once common across Europe, the Eurasian beaver was hunted and trapped to near-extinction by the early 20th century. However, restoration projects have reintroduced beaver populations across the continent, with more than 1.5 million animals now making their home in European freshwaters.

Beavers are often termed ‘ecosystem engineers’ due to their ability to create complex and diverse wetland habitats through tree felling and dam building. As beaver populations spread across Europe, there is increased focus on the impacts of this activity, both to human and non-human life.

As shown in the MERLIN project work in Sweden, beaver reintroduction is increasingly seen as a key part of a nature-based solutions approach to restoration. The ponds, pools and floodplains they create around streams and rivers have been shown to help reduce flooding and improve water quality through trapping sediment.

A key question for beaver restoration programmes is how their activity influences the wider ecological health of their rivers and streams they inhabit. Existing studies have shown the presence of beavers boosts populations of aquatic insects, amphibians, birds and bats, whilst providing nursery grounds for juvenile fish.

A new study by scientists in Germany focuses on the impact of beaver populations on three streams in North-Rhine Westphalia – an area in the west of the country, adjacent to the Netherlands and Belgium. The team studied aquatic insect populations in three streams: the Thönbach, Weberbach and Weiße Wehe. On each stream, the team took samples around beaver habitats, and again where the animals were not present.

“What is striking,” says Sara Schloemer, lead author of the study, “is that no species disappeared in the beaver territories we studied. On the contrary, over 140 additional species were present in these areas, compared to the sites without beavers.”

“By increasing aquatic habitats beavers boost both species abundance and richness,” Schloemer continues. “In our study, the area of aquatic habitats increased six-fold due to beaver activities. The abundance of bottom-dwelling aquatic insects increased more than four times over.”

The so-called ‘macroinvertebrates’ studied by the team are valuable proxies for the health of the wider ecosystem. These aquatic insects – including beetles, mayflies and caddis flies – provide vital food for fish, bats, amphibians and birds, and their population dynamics can reveal important insights about water quality and pollution.

“The concern sometimes expressed by conservationists that beavers will destroy free-flowing, strong-flowing stream sections in their territories is therefore unfounded. In fact, the beaver creates fascinating additional habitats such as ponds, dams, swamps without free-flowing sections disappearing completely,” says Daniel Hering, the final author of the study.

“Beavers are rapidly expanding their range in Europe,” Hering continues. “This sometimes causes problems with land owners and land users. At the same time, they really contribute to diversity floodplains and to restore streams.”

Writing in Freshwater Biology, the research team suggest that their findings show that beavers can offer a cost-effective means by which small stream floodplains can be enhanced. As such, they emphasise the importance of their reintroduction to areas where they were formerly present.

“Beavers reintroduce habitat features that were once characteristic of natural stream ecosystems and that are missing from most contemporary European streams,” Hering says. “Beavers greatly enhance the diversity of aquatic insects and provide habitats for a multitude of species.

“By considering the full range of habitats created by beavers, we can ensure more accurate assessments and make informed decisions for conservation and restoration efforts,” Hering concludes.

///

Restoring our natural ecosystems is a task that is never really finished: science progresses; governments change; technology advances; society shifts; funding pots appear and disappear. And all the time, our rivers, lakes, streams and wetlands are a constant; their fate determined by the choices we make about them. In a time of rapid ecological loss and the ongoing climate emergency, it can be hard to think hopefully about the future of our ecosystems.

In the new episode of the MERLIN podcast we hear from four inspirational young scientists who are helping restore Europe’s freshwaters, and with it, hope for the future of our natural world. The four scientists all work on the EU MERLIN project, but each have their own research focus. They are Miriam Colls Lozano from the University of the Basque Country, Andrea Schneider from the University of Duisburg-Essen, Viviane Cavalcanti from DELTARES and Joselyn Verónica Arreaga Espin from BOKU.

We hear about the challenges of bringing disparate communities together through freshwater restoration, fostering exchange and collaboration between different communities, thinking creatively about funding restoration in the future, and strategies for bringing the public and policy makers on board with ambitious restoration programmes. The thread that runs through all these themes is the need for good communication in fostering positive change for the future.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Finance, monitoring and people: planning the ambitious restoration of Europe’s ecosystems

Last year, Europe adopted an ambitious new law committing to restore the continent’s degraded ecosystems.

The Nature Restoration Regulation is the first continent-wide, comprehensive law of its kind. It aims to reverse biodiversity loss, strengthen climate resilience, and support long-term environmental and economic sustainability. Previously termed the Nature Restoration Law, the legislation compels European countries to restore at least 20% of their degraded ecosystems by 2030, and all degraded ecosystems by 2050.

Each EU Member State must now develop a National Restoration Plan to kickstart the new legislation’s ambitious goals. These restoration plans – due in 2026 – will offer a roadmap for how Europe’s ecosystems can be brought back to life over the coming decades.

A key part of this process involves absorbing lessons from the cutting-edge restoration research and practice currently taking place across Europe. Four major EU nature restoration projects recently met in Brussels to discuss evidence-based recommendations to help European countries develop their National Restoration Plans.

The four projects – MERLIN, REST-COAST, SUPERB and WaterLANDS – have spent the last four years developing innovative approaches to restoring Europe’s freshwaters, coastlines, forests and wetlands. The projects share a focus on the potential of nature-based solutions – using natural processes to help benefit both people and nature – to help achieve this goal.

Three key themes emerged from the Brussels meeting. First, the importance of securing adequate, long-terms funding for restoration. Second, the need to develop robust monitoring, indicator and prioritisation tools to help make good decisions about long-term restoration management. Third, the vital role of engaging the public and policy makers to generate trust and support for restoration initiatives.

Financing long-term restoration projects

Funding long-term restoration projects through National Restoration Plans is a key challenge for EU countries. Whilst there is no dedicated EU funding stream to support the plans, they can be supported through existing national and EU programmes – such as the Common Agricultural Policy – as well as innovative private sector investments such as carbon credits and payments for ecosystem services.

The four projects highlight a number of challenges in accessing funding through these channels. They suggest that biodiversity and carbon monitoring can be tricky to link to financial outcomes, and as a result private companies can be hesitant to invest in restoration due to concerns over ‘greenwashing’. Similarly, ‘nature credit’ schemes can be challenging to implement and regulate due to difficulties over monetising ecological gains whilst avoiding negative outcomes.

Further, it’s highlighted that awareness of new financial schemes is often low amongst local and national authorities. In particular, there is the need to communicate the potential of business models based on nature-based solutions approaches to help stimulate their uptake.

The four projects offer individual lessons on how to overcome these barriers. For example, WaterLANDS identify three steps: building knowledge on sustainable finance; taking action to test new business models; and identifying pathways to upscale innovative finance models across the continent. MERLIN has built a financial workflow for restoration activities, and offers ‘off-the-shelf instruments’ to support financial solutions for restoration.

The projects state that to attract private sector investment into restoration, it is vital to demonstrate that revenue generation and business opportunities from nature are viable. They highlight the need to develop methods and tools that value the benefits nature provides to people.

They advocate for public-private partnerships where nature restoration is regarded as an investment which can not only generate revenue, but also avoid future costs and risks, for example as the result of flooding or drought.

To support such schemes, there is the need to implement financial instruments. For example, REST-COAST explore the application of ten financial instruments – including green bonds, blockchain tokens and eco-labels – in supporting restoration. Both MERLIN and WaterLANDS outline the difficulties of quantifying costs and revenues in freshwater ecosystems, particularly over long timescales.

The four projects state that there is a need for governance strategies that help combine public funding with private sources to support the long-term financing of restoration, whilst also overcoming the multiple challenges these approaches can involve.

Upscaling nature restoration: monitoring, indicators, prioritisation, trade-offs

Upscaling is an increasingly-heard term in European restoration: it points to the need for ecosystems to be restored and joined up, not only at individual sites, but across a continent-wide network of living habitats. The four projects highlight the need for effective monitoring strategies to be developed to allow restoration managers to address different priorities and trade-offs in helping foster this European network of healthy, diverse ecosystems.

Monitoring is crucial for understanding the impacts of restoration activities, and allow managers to track progress over the long timescales it takes for a forest to grow or a peatland to form. SUPERB has developed a series of restoration work plans that help managers address factors like site selection, monitoring and stakeholder strategies, whilst MERLIN has produced a Flexible Indicator System which helps projects align their environmental, social and economic impacts with those of the EU Green Deal.

All four projects highlight the potential of innovative new monitoring techniques like eDNA, AI, citizen science and acoustic modelling in supporting large-scale data collection. Moreover, they point to the wealth of existing data already available to help guide restoration projects, such as that collected in the Water Framework Directive. There is a need to make such large and complex datasets more accessible to restoration managers seeking to plan and monitor their own projects.

Upscaling nature restoration across the continent will require significant prioritisation and trade-offs to help bring healthy, diverse ecosystems back into daily life. Prioritisation in National Restoration Plans could focus on factors including feasibility, ease of implementation, landscape connectivity and actions that deliver multiple benefits, or on the protection of rare or threatened habitats. The projects highlight the potential of economic cost-benefit analyses to help assess such trade-offs.

Effective restoration requires targets and monitoring systems that address multiple goals simultaneously. For example, restoration work on the Emscher River in Germany – supported by MERLIN – has improved water quality and habitat whilst providing new spaces for recreation. Similarly, WaterLANDS work on the Great North Bog in the UK is restoring peatlands for increased biodiversity and carbon storage, whilst simultaneously helping boost water quality and flood mitigation downstream.

However, such work often involves trade-offs, as found by the SUPERB project in their projects along the Danube river floodplains. Here, intensive poplar plantations are being increasingly converted to natural oak forests to benefit biodiversity, but this process temporarily reduces carbon storage and timber yield. To navigate complexities like these, SUPERB has developed a series of interactive maps to highlight policy coherences (and incoherences) between national forest laws and the Nature Restoration Regulation across Europe.

The importance of people: stakeholder engagement and governance challenges

Nature restoration is never solely about biodiversity and ecosystems: it is deeply related to people, too. As a result, our social, cultural, economic and political systems are entwined in restoration projects, particularly when the ambition is to mainstream restoration across the continent.

As a result, the four projects highlight the need for effective governance and stakeholder engagement in gaining trust and support for restoration projects. They outline a range of governance challenges that EU Member States will face when designing National Restoration Plans. These include addressing conflicting interests and priorities amongst different communities, ensuring the uptake of restoration on the ground, and mobilising ongoing public support.

Sensitively and effectively managing these challenges is key to the long-term success of restoration projects, the contributors argue, and can help maximise their social, economic and ecological benefits. Evidence from the four projects shows that stakeholder engagement, collaborative decision-making and holistic thinking are central for addressing these challenges.

Key to this work is integrating top-down approaches – which are led by national decision makers – and bottom-up approaches – which are led by public and community groups – into restoration planning. The four projects highlight that in so doing, National Restoration Plans can align with existing European policies whilst ensuring national level commitment and local buy-in based on trust and integration.

All four projects share this multi-level engagement with people in making restoration projects happen. For example, REST-COAST’s pilot sites are based on collaborative, ‘living lab’ decision-making processes which bring together multiple perspectives on restoration. Similarly, WaterLANDS has developed detailed guidelines on deliberative decision-making processes which integrate social and economic considerations with ecological assessments.

The four projects also highlight the need to address governance barriers and policy incoherences which can hinder ambitious restoration projects. A key obstacle is the difficulty of aligning different priorities, such as biodiversity conservation, agriculture, forestry and urban development. This is compounded by the fragmented nature of policies across European, national and local levels, and the short political cycles underpinning government decision-making.

These challenges can be overcome by developing integrated policies that encompass multiple interests – for example, from climate, water and environmental policy – from EU to national and local levels. A holistic perspective which focuses on the whole landscape or ecosystem can help integrate nature restoration goals into such broader objectives, the four projects suggest.

Finally, the four projects emphasise the need for effective stakeholder engagement in fostering trust, support and uptake for restoration projects. Engagement is different from communication: it requires open dialogue, trust building and co-creation, and it aims to ensure that all interests and values around a landscape are meaningfully considered and integrated.

This article offers only a snapshot of the detailed recommendations offered by the four projects, which can be read in full in the EU report here. The insights it offers should be hugely valuable in helping scaffold the next chapter of ambitious ecosystem restoration across Europe.

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities: artistic riverine insects create colourful cases from unusual materials

If you’re a long-time follower of the Freshwater Blog, you might remember our Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities project from more than a decade ago. That website has since washed away down the rivers of time, but we thought it was the right moment to showcase our collection of curious freshwater plants and animals again. So keep your eyes peeled over the coming months as we dust off the Cabinet and celebrate the wonderful world of freshwater life!

///

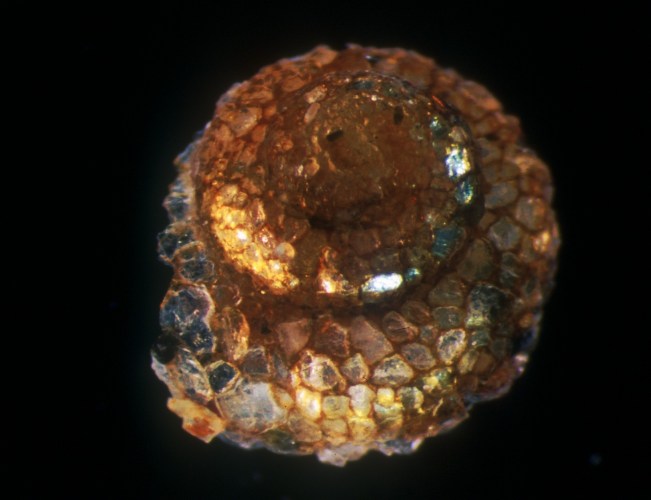

Caddis larvae – Trichoptera

Guest curators: Prof. Daniel Hering (University of Duisburg-Essen) and Gerhard Laukötter

Many animal species are protected from predators, desiccation or disturbance by a thick shell or skin. Only few, however – leeches, midge larvae and butterfly larvae – are capable of building cases to artificially protect them from the environment. Unsurpassed as artistic architects of such artificial cases are tiny caddis larvae, which live amongst the rocks, vegetation and rubbish on river beds. These unique little creatures have developed the curious ability to use these raw materials to create colourful and unusual protective outer tubes.

Caddis larvae are the larval stages of caddis flies (Trichoptera), of which about 12,000 species are known worldwide. Larvae of almost all species are aquatic. Larvae of about half of the species construct transportable cases, protecting soft-skinned parts of the body and in which the larvae can retreat in case of danger. All species protect their defenceless pupal stage with artificial cases, which are firmly attached to the river bed.

Depending of the larval habitat size and form of caddis cases vary, resulting in a large number of unusually constructed cases: round and square tubes, cases in the form of a turtle shell or a snail shell, sand tubes punctuated by thick stones and multi-story cases with sophisticated ventilation systems! Fascinatingly, caddis larvae use very diverse materials for case construction, including: self generated silk; sand of a defined grain size or of different grain sizes; small pieces of wood cut at an exact size by the larvae’s mouthparts; and small parts of leaves, roots or of reed stalks.

Sand

Sericostoma larvae bind small sand grains together in a seemingly jointless, curved tube. Similar material is used by representatives of the genera Molanna (in flat tubes) and Helicopsyche (in wound cases, amazingly similar to a snail shell).

Silk

Larvae of the genera Micrasema and Setodes are specialized weavers, with cases made of pure silk. The diameter of the tube increases when the larvae growths.

Wood and vegetation

Some caddis larvae species (e.g. Crunoecia which inhabits springs), cut wood fragments to a standardized size with which perfectly squared cases are built. Other species don’t care for geometry at all and assemble chaotic cases using all available wood and leaf material without any real construction plan. The important outcome – protecting the larvae – is nevertheless achieved.

Unusual and artificial material

When these preferred materials are not available, most species resourcefully change to building cases out of other more unusual material, with a range of strange and curious results.

In springs with low current flow, coarse sand and gravel is often absent; and the riverbed is covered by fine sand. Species usually preferring coarse particles have to change to completely different items: using seeds, small mussel and snail shells, regardless of whether they are empty or still inhabited! On rare occasions, a fascinating form of kleptomania can be observed. Here, the cases of small larvae are used by larger larvae for building their own cases. As with snails, this is done regardless whether or not the cases are still inhabited.

Artificial material is also used by caddis larvae, and sometimes even preferred. Small fragments of red bricks or cement, fibrous tissue, even small pieces of paper or plastic have been observed as parts of colourful caddis cases.

As caddis larvae are generalists in selecting building material, several scientists have exposed larvae in laboratories. In some cases there was a scientific rationale for this. For example, larvae can be marked to observe their migration, as colourful cases are more easily found in a stream.

Caddis larvae reared on a bed of small glass pieces may build a transparent case – which proves useful for scientists hoping to observe the behaviour of the larvae inside. Some biologists have offered fragments of corals, nacre, opal, malachite, lapis lazuli, garnet, rock crystal or turquoise to caddis larvae. These materials result in precious and colourful cases.

More information:

- Higher resolution versions of these caddis larvae photos and others at the BioFresh flickr

- More information on caddis larvae from the Field Studies Council

- Wikipedia page

New sources of funding are needed to meet the needs a growing ecosystem restoration movement in Europe, according to a newly published report.

In particular, ambitious restoration initiatives which help bring Europe’s freshwaters back to life require financial support from both private and public sources in order to fulfil their potential.

Researchers from the EU MERLIN project explored the potential for restoration managers to diversify how they raise funds to support their work. They highlight the need for creative thinking to address the ‘funding gap’ in a realm traditionally supported by public grant funding.

The report outlines that whilst private finance has the potential to support ambitious freshwater restoration in Europe, there are a number of barriers to its uptake. These include specialised language, perceptions of reputational risk, and the difficulties of writing business plans based on the financial benefits produced by restoration.

Committed programmes of communication and collaboration are needed between restoration managers and private sector financiers in order to unlock shared potential, the report states. This process should be underpinned by support programmes, pilot initiatives and expert guidance, the authors advocate.

“We have collected documentary evidence and empirical lessons from twenty cases over three years to shed light on the factors that drive and hinder collaboration between restoration teams and private capital,” says co-lead author Gerardo Anzaldua from ECOLOGIC.

“By looking at how the restoration community communicated, perceived the issues, and got involved—as well as the structures they work within—we took a different approach that adds to ongoing work on funding freshwater restoration and nature-based solutions,” Anzaldua says.

“Restoration teams show a great variety of views on the best strategies to scale up and diversify funding for restoration initiatives,” continues co-lead author Josselin Rouillard from ECOLOGIC. “Some are more equipped than others in reaching out to the private sector. Many are concerned by the resources that would be needed to effectively reach out and create lasting partnerships. Working with the private sector really requires a lot more thinking on the benefits and opportunities that restoration offers for economic activities. It really is a shift in paradigm.”

“Scaling up to a European level in a harmonised, homogeneous way, is unrealistic,” says Gerardo Anzaldua. “Restoration teams need support along their diversification journey, but the type of assistance needed is quite distinct at each stage. It starts with learning on how to communicate with the private sector, understanding their language and needs, all the way to setting up new governance arrangements to have the right accountability and reporting systems. There is no standardised ‘cook-book’, as every context is different.”

“A lot is at stake, as the risks and damages of the ongoing environmental crises are mounting fast while public budgets become increasingly strained,” adds Josselin Rouillard. “Yet there are rightful concerns about the principles and metrics that drive private funding and finance into restoration. It is thus important to reflect on what the pre-conditions are for a successful partnership between the restoration community and the private sector. Safeguards are needed, with serious consideration to possible effects in terms on ownership and access, wealth distribution, equity, and wellbeing.”

“While we focused our work on the restoration community, there is as much work on the side of private donors, lenders, and investors,” Gerardo Anzaldua concludes. “There is scope for simplifying the language but also for increasing their restoration literacy. Improving communication between the two communities is really the first step before interests and priorities can even start to be aligned.”

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.