A new open-access online platform hosting datasets on European aquatic ecosystems, biodiversity and Ecosystem-Based Management has been launched this month. The AQUACROSS Information Platform (IP) is designed to provide scientists and environmental managers with integrated datasets on aquatic systems across Europe at a variety of scales.

The information platform has been produced through a collaboration between the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and the AQUACROSS project. AQUACROSS is an EU Horizon 2020 project which aims to support European efforts to protect aquatic biodiversity and ensure the provision of aquatic ecosystem services.

The project, which has been active since 2015, seeks to advance both knowledge and application of Ecosystem-Based Management in aquatic ecosystems, to support the achievement of EU 2020 Biodiversity Strategy Targets.

Image: AQUACROSS

AQUACROSS project co-ordinator Manuel Lago from the Ecologic Institute in Berlin says,

“The AQUACROSS IP is an unprecedented effort to combine relevant data for the interdisciplinary analytical needs required for the protection of aquatic biodiversity. The AQUACROSS IP ensures a single point of entry for freshwater, coastal and marine related information to be used in general and case-study integrative assessments.”

The AQUACROSS IP is designed to help support more effective European environmental policy and management by helping share and connect existing spatial datasets at local, regional, national and international levels.

The information platform will help provide water managers and policy makers with a clearer, more detailed picture of how European waters – both freshwater and marine – are responding to the multiple pressures from human activity and climate change.

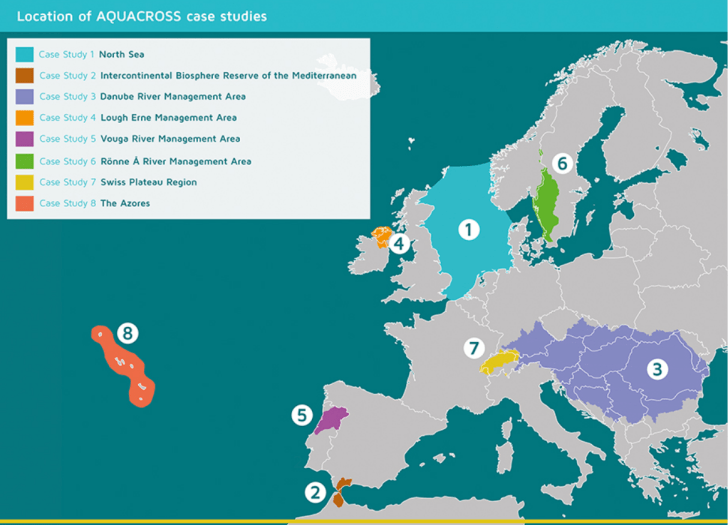

The eight AQUACROSS case studies which can be explored in the new Information Platform. Image: AQUACROSS

Users of the AQUACROSS IP can access datasets from aquatic case studies across Europe, and analyse, visualise and publish the information they contain. At present, there are 580 different datasets available on the platform, many of which were produced through research in eight AQUACROSS case studies.

These case studies are:

- North Sea – trade-offs in ecosystem-based fisheries management to achieve Biodiversity Strategy targets;

- Intercontinental Biosphere Reserve of the Mediterranean, Spain/Morocco – nature-based solutions in transboundary aquatic ecosystems;

- Danube River Basin – harmonising inland, coastal and marine ecosystem management to achieve aquatic biodiversity targets;

- Lough Erne, Ireland – management and impact of Invasive Alien Species;

- Ria de Aveiro Natura 2000 site, Portugal – integrated management of a complex socio-ecological coastal ecosystem;

- Lake Ringsjön and Rönne å Catchment, Sweden – understanding eutrophication processes and restoring good water quality;

- Swiss Plateau – biodiversity management of rivers in densely populated landscapes;

- Azores – ecosystem-based management in a Marine Protected Area with multiple human pressures.

Looking over the Swiss Plateau, one of the AQUACROSS case studies. Image: AQUACROSS

The AQUACROSS IP structure has been designed following guidance from the European INSPIRE Directive, which encourages environmental data sharing and access initiatives. The platform has been developed based on existing open-source CKAN software, following the Open Source Software Strategy and the New Interoperability Framework recommendations from the European Commission.

Juan Arevalo from the IP developing team working at IOC-UNESCO says,

“The development of the AQUACROSS Information Platform is based on CKAN software. This open source framework allowed us to integrate all the requirements from our project stakeholders. I would encourage anyone to use CKAN to develop open data portals given its interoperability with other system and the flexibility for development.”

The AQUACROSS IP is an ongoing, growing project. New resources will be added to the platform in the future, and users are encouraged to contact the managers of the IP with suggestions of relevant datasets which could be linked to the platform. The contact email is – aquacross.IP (at) unesco.org.

More information:

Less than half of European surface waters reach good ecological status, according to new EEA report

The Neckar River at Ladenburg, Germany, which has significant hydromorphological alterations. Image: EEA

Less than half of Europe’s rivers, lakes and estuarine waters reach good ecological status, according to a recently published European Environment Agency report. Only 40% of European surface water bodies were found to be in a good ecological state, despite significant policy and management initiatives in recent decades to conserve and restore them. Roughly the same percentage (38%) of surface waters reach good chemical status, whilst nearly half (46%) do not.

The EEA report is based on data from EU-member states monitoring their surface and ground waters as part of the Water Framework Directive River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs). The report is the first overall assessment over European waters since 2012, and covers the second round of RBMP reporting. It contains data on over 130,000 water bodies across Europe, which have been monitored over the last six years.

What is ecological status?

Ecological status is an assessment of the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems, and is intended to show the ecological impacts of pressures such as pollution and habitat degradation. It is calculated based on monitoring of biological quality elements (such as fish, insects and plankton), physico-chemical elements (such as nutrient levels, organic pollutants and acidification), and hydromorphological elements (such as water flow, channel shape, and barriers such as dams and weirs). Broadly, then, ‘good’ ecological status means that communities of plants and animals can thrive in aquatic habitats which show minimal impacts of human alterations. ‘Good’ ecological status is the goal for water management under the Water Framework Directive.

Image: EEA 2018

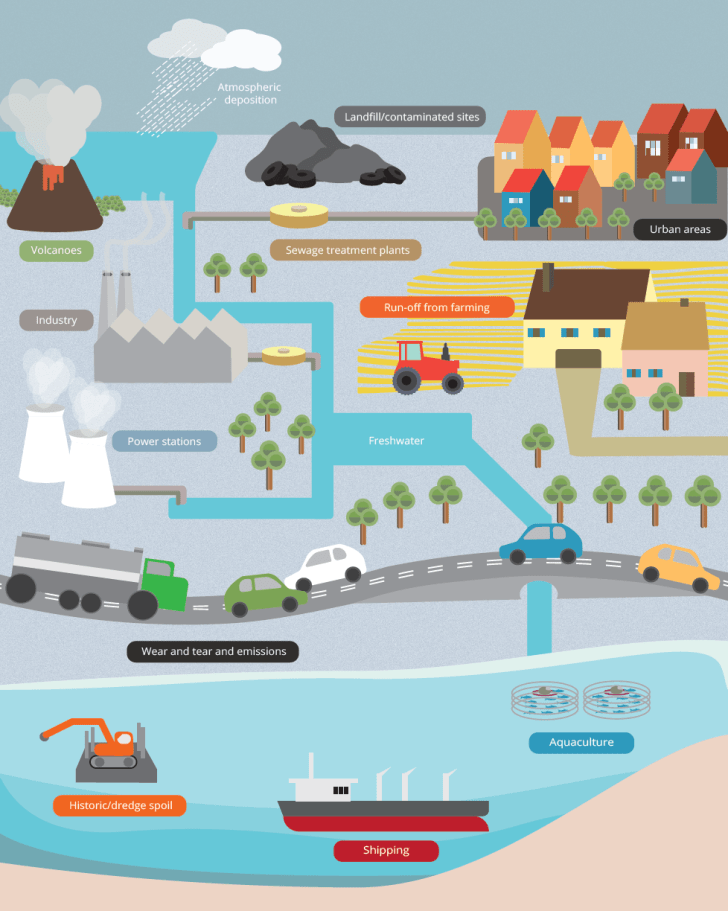

Key pressures on European surface waters

The most significant pressures on surface water bodies were from hydromorphological alterations (such as river straightening, water impoundment and the construction of dams and weirs) and diffuse pollution (particularly of fertilisers from agriculture). Mercury pollution – from atmospheric deposition and urban waste water treatment plants – was a key cause of many water bodies failing to reach good chemical status. The countries with the lowest proportion of water bodies in ‘good’ ecological and chemical status were in heavily-populated and industrialised areas of northern Europe – particularly in south-east England, Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.

Groundwaters in better condition

Groundwaters were generally found to be in better condition across Europe, with 74% of European groundwater areas found to be in good chemical status, and 89% found to be in good quantitative status (i.e. their water stock). Nitrates from agricultural activity and sewage systems were the primary source of groundwater pollution. Water abstraction for public water supplies, agriculture and industry was the key cause of groundwaters failing to achieve good quantitative status.

Sources of water pollution across Europe. Image: EEA, 2018

Reflecting on the second River Basin Management Plan reports

It is difficult to properly compare the results of the first and second RBMPs, as European water monitoring programs have been expanded and improved over their period of implementation. But, whilst these monitoring improvements have given scientists and managers a better picture of the stressors and pressures affecting European waters, there appears a long way still to go in successfully mitigating their harmful effects.

“Thanks to the implementation of European water legislation in the Member States, the quality of Europe’s freshwater is gradually improving, but much more needs to be done before all lakes, rivers, coastal waters and groundwater bodies are in good status. Tackling pollution from agriculture, industry and households requires joint efforts from all water users throughout Europe,” says Karmenu Vella, EU Commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries.

The report states that most European member states have made significant efforts to improve water quality and reduce hydromorphological pressures on their surface waters. The original intention of the Water Framework Directive – implemented in 2000 – was that all member states should achieve good status in their surface and ground waters by 2015. This has obviously not been achieved, despite the coordinated efforts of policy makers, water managers and scientists across Europe under the WFD.

It is increasingly evident, however, that the ecological impacts of aquatic restoration measures can take a number of years to be realized, especially in complex multiple stress environments. The authors of the EEA report optimistically suggest that by the time the third RBMPs (taking place 2019-2021) are reported upon, the conservation and restoration measures implemented in the first two rounds will have caused significant positive progress towards good ecological status in water bodies across Europe.

‘Making room for the river’ on the Swindale Beck restoration project in the English Lake District. Image: Lee Schofield | RESTORE Project

The promise of integrated water management

The report calls for an increased focus on integrated water management as a means strengthening WFD implementation and impacts. Its authors highlight three areas in which this could be achieved. First, they advocate the use of management concepts such as the ecosystem services approach and ecosystem-based management as a means of co-ordinating efforts across related EU policies on the marine environment and terrestrial biodiversity. Second, they highlight the potentials of ecological management which works with dynamic natural processes, such as river and floodplan restoration through ‘Room for the River’ type schemes.

Finally, they call for better co-operation between water authorities and other sectors such as agriculture, transport and energy. They highlight Europe 2020 – the EU’s strategy for the growth of a ‘greener’, more environmental economy – as a framework for fostering sustainable water management across sectors.

“We must increase efforts to ensure our waters are as clean and resilient as they should be — our own well-being and the health of our vital water and marine ecosystems depend on it. This is critical to the long-term sustainability of our waters and in meeting our long-term goals of living well within the limits of our planet,” says Hans Bruyninckx, EEA Executive Director.

Clear waters in the Čunovo Dam on the Danube River in Slovakia. Image: Miroslav Petrasko | Flickr Creative Commons

Rivers across the world support rich biodiversity, yet are some of the most threatened global ecosystems, as a result of multiple pressures including pollution, water abstraction, habitat alteration and dam construction. As a result, river conservation and restoration are key topics for scientists, environmental managers and policy makers globally.

A new book Riverine Ecosystem Management: Science for Governing Towards a Sustainable Future provides a cutting-edge overview of contemporary approaches to river management. Available as a free PDF and ePub download, the book is edited by Stefan Schmutz and Jan Sendzimir from BOKU – University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences at the Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management in Vienna.

Key themes in river management

The book is split into four sections. The first gives an overview of some of the key themes in current river management, namely human impacts, mitigation and restoration. Historical human river uses and impacts are surveyed alongside a series of contemporary river pressures, including alterations to river morphology and hydrology, dam construction and hydropeaking, sediment dynamics, habitat fragmentation, nutrient pollution and recreational fisheries.

The section encompasses emerging threats to river health and status, particularly in chapters by Florian Pletterbauer and colleagues on climate change, and by Ralf B. Schäfer and Mirco Bundschuh on chemical pollution.

Diverse woody habitat on the Lafnitz River in Austria. Image: Graf & Schmidt-Kloiber

Approaches in contemporary river management

The next section provides examples of contemporary approaches for river management and governance. Again, the focus is extremely timely, covering relevant legislative frameworks, integrated river basin management, adaptive management and transboundary water resource management, alongside methodologies for sampling and archiving biological data, such as in Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber and Aaike De Wever’s chapter on Biodiversity and Freshwater Information Systems. Schmidt-Kloiber and De Wever outline the value of online networks for freshwater data such as the Freshwater Information Platform.

A theme that runs through the book is that river ecosystems should be understood (and managed) as integrated ‘social-ecological systems’ in which nature and culture interact. As a result, this second section provides guidance and resources on identifying ecosystem services in river basins, and in fostering public and Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) engagement and education in river management. Chapters on this theme are written by Kerstin Böck, Michaela Poppe, Christoph Litschauer and colleagues.

Sunset on the urban Danube River in Vienna. Image: Carola Moon | Flickr Creative Commons

Case studies of river management

The third section provides five case studies of river basin management, which illustrate and tie together many of the themes outlined in the previous sections. Three aspects of water management – hydropower, floodplain dynamics and uses, and sturgeon populations – on the Danube River in Central and Eastern Europe are described. These three case studies – written by Herwig Waidbacher, Stefan Preiner, Thomas Friedrich and colleagues – give an indication of the many challenges associated with the environmental management of a large, transboundary river with diverse habitats and competing human interests.

In Burkina Faso in West Africa, Andreas Melcher and colleagues discuss the need for co-ordination of fisheries management at national and local scales, supported by ecological monitoring programs, as a means of supporting sustainable fisheries for local communities. Finally, on the lowland Tisza River in Eastern Europe, Béla Borsos and Jan Sendzimir outline the steps needed to develop an integrated land development (or ILD) management approach in a complex and dynamic river basin.

The frozen Tisza River at Szeged, Hungary. Image: Zoltán Bagi | Flickr Creative Commons

Adaptive and interdisciplinary approaches to managing river systems

In the fourth and final section, the editors draw the book together, emphasising the need for river management to understand the ways in which social and environment systems link and interact in river basins. They highlight the possibilities of new ecological monitoring techniques as well as data management and mining techniques to inform river management, but underline the need for management to be adaptive to an increasingly complex and uncertain world.

Co-editor Stefan Schmutz says, “Despite a rich history of publications on riverine ecosystem management, this book is the first to concisely convey to a broad audience of students, academics and practitioners the frontiers of science and policy for sustainably restoring and managing rivers.”

Co-editor Jan Sendzimir continues, “Unprecedented uncertainty from global change requires an approach that integrates riverine ecosystem understanding and management requirements and options within an interdisciplinary framework. This book applies such a framework to show through a number of case studies how ecosystem and management theories and applications can be successfully used to re-establish and sustain the functional vitality of riverine ecosystems.”

The Open-Access e-book

Arranged as a series of short, accessible chapters, and richly illustrated with colour photographs and diagrams, Riverine Ecosystem Management: Science for Governing Towards a Sustainable Future is likely to prove useful for water managers, academics, students, policy makers and NGOs. Its clear style makes it open to interested non-specialists, too. The e-book also helps communicate a variety of research findings from EU- funded projects, including AQUACROSS, MARS and BioFresh.

There is clearly demand for such a publication – so far the e-book has been downloaded over 53,000 times in two months. For anyone seeking to understand the key debates, approaches and directions in contemporary river management, this is an invaluable resource.

Reporting from MARS: multiple stressor science and management in European aquatic ecosystems

MARS has investigated how multiple stressors affect European rivers, lakes and groundwaters over the last four years. Image: Symbolique 2006

After four years of research on multiple stressor interactions and impacts in European aquatic ecosystems, the EU FP7 MARS project has published its final project report (pdf).

The project began in 2014, and investigated how the complex ‘cocktails’ of stressors such as water pollution, habitat loss and climate change affected ecological status and ecosystem services in rivers, lakes and groundwaters across Europe.

The focus of the MARS project was tailored to support water managers and policy makers, in particular through advising the implementation and 2019 update of the Water Framework Directive and the Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Water Resources.

The final MARS report gives a breakdown of project activities and results over the last four years. Significantly, it shows that the project has resulted in over 230 scientific publications, numerous policy briefs and factsheets, and a suite of online tools for water management. This blog post gives a brief overview of some of the research highlights, and more detailed information can be found in the project report.

The IGB LakeLab in Lake Stechlin, Germany – a ‘floating laboratory’ for MARS experiments. Image: HTW Dresden-Oczipka

Multiple Stressor Research and Management

An initial MARS literature review of 219 existing journal articles on multiple stressors found that nutrient stress was involved in most (71–98%) of multiple stress interactions in rivers, lakes and estuary (or ‘transitional’) waters, and just under half (42%) of those in groundwaters. Their impacts were different depending on habitat type, mostly as a result of different hydromorphological (i.e. the water body banks and bed) characteristics and alterations. As a result, nutrient enrichment and hydromorphological alteration was the most common stressor pair overall, particularly in rivers and transitional waters.

MARS research was carried out at three different scales. At the water body scale, experiments with mesocosms and river flumes were used to investigate stressor interactions, and their impacts on ecological status and ecosystem services. At the catchment scale, modelling and empirical approaches were used to characterise the relationships between multiple stressors and ecological responses, functions and services, across 16 European river basins.

Finally, at the European scale, large-scale spatial analyses were carried out to identify relationships between stressor intensity, ecological status and service provision for large transboundary rivers and lakes. This research produced a series of European multi-pressure maps, with threshold values for four important pressure types, and a Stressor Analysis Tool for water managers.

The HyTEC field station in the Austrian Alps – the site of MARS stream experiments. Image: Christian Feld

Key messages from MARS

Around one-third of the 156 MARS case studies across Europe showed significant multiple-stressor effects. As a result, it can be confidently stated that multiple stressors are an important contemporary topic for aquatic science and management. However, a key message from MARS research is that there are rarely predictable relationships between stressor causes and biological effects, and that the characteristics of the local environment can mask or interfere with observed stressor effects.

As a result, it is necessary to investigate and manage the multiple stressor interactions and impacts for individual water bodies and river basins depending on their local biological and geographical characteristics. These can be assessed, diagnosed and managed using a suite of MARS online tools.

In short, what is required is aquatic science research that investigates the direct causes of deteriorated ecological status in rivers and lakes across Europe, a task which can be aided by advances in multiple stressor data collection and diagnostics. This is a key focus for managing and restoring complex aquatic environments under multiple pressures, both now and in the future.

Multiple Stressor Tools

MARS project findings have been integrated into practical and accessible online tools to support water management.

They include:

- Freshwater Information System – including an information library and factsheets on multiple stressors, ecosystem services, case studies and storylines for future environmental scenarios, alongside a model selection tool and guidelines for river basin management;

- Diagnostic Tool for Water Bodies – designed to help water managers diagnose and mitigate multiple stress impacts on rivers and lakes;

- Model Selection Tool – an overview of 21 available computer modelling tools for river basin management;

- Scenario Analysis Tool – allows users to visualise and map multiple stressor interactions and impacts (both present and projected) at the European scale;

- Bayesian Belief Models – designed to help predict biological responses to aquatic conservation and restoration measures under projected future environmental scenarios (see approach here).

Visualisation of an additive pair of stressors – riparian vegetation alteration and phosphate levels – and how they might be managed towards good ecological status, as shown by the diagonal threshold line.

One innovative MARS output for water managers is the visualisation of how stressor-pairs can be managed towards good ecological status. Individual stressors are shown on the x and y axes of the ‘heat map’ diagrams, which are generated by computer modelling, and show a threshold line across which multiple stressor levels should be reduced in order to achieve good ecological status.

Summing up

Reflecting on the last four years, MARS project co-ordinator Sebastian Birk says,

“MARS was a fascinating project, joining the forces of highly skilled scientists across Europe towards unraveling the multi-stressor maze. I feel very honoured for this chance of coordinating such a great team. Most project partners knew each other since the early days of the Water Framework Directive, and this long-standing confidence and trust in each other made this project a delight. Daniel and me would like to express our sincere thanks to all MARS colleagues for this memorable experience! With posting the final project report, this will be kind of the last ‘official’ MARS blog entry. However, there is much more on MARS and beyond, so stay tuned to this channel.”

Read the MARS Final Report (pdf)

Read the ‘Messages from MARS’ blog post

Explore the MARS website

Restored river section five years after restoration with riparian vegetation consisting of grasses, shrubs and trees. Photo: Christian K. Feld

Safeguarding the banks and margins of streams and rivers has a key role to play in ensuring river health. This is the major conclusion from a new international study recently published in Water Research.

The authors of the new study synthesised the findings of more than 100 river management studies, many of which addressed the effects of riparian restoration on riverine habitat and biological conditions. It is widely acknowledged that riparian plants provide food for aquatic organisms, and can mitigate water temperature increases under climate change. Riparian zones can also provide valuable ‘buffer zones’ for run-off from farming and urban areas, preventing pollutants from reaching the river channel. Yet such riparian effects are not to be taken for granted.

Rivers are increasingly threatened by pollution, habitat modification and over-exploitation. Based on the results of the first Water Framework River Basin Management cycle, in 2012 the European Environment Agency (EEA) concluded that more than half of the European river network is damaged by severe human alterations. This picture appears even worse when individual country’s results are considered.

Riparian vegetation is often degraded to a one-row tree line. This may provide shade during summer, yet fundamental functions of riparian vegetation such as nutrient and fine sediment retention cannot be fulfilled. Photo: Christian K. Feld

River restoration approaches generally seek to improve river health, but often struggle with the identification of suitable management options. The team of researchers behind the new study addressed this need during the EU MARS project by reviewing available scientific literature. The scientists analysed the ecological role of riparian vegetation types as well as their configuration and spatial extent. Riparian features were then related to the level of restoration success observed in individual studies.

These results can then be applied to help guide future river restoration activities. Restoration success was evaluated through measures such as the efficiency of nutrients and sediments retention or water temperature ‘dampening’ as a result of riparian vegetation. Over a longer term, the effects that riparian vegetation had on riverine plants and animals could be evaluated.

Benthic invertebrate (caddisfly larvae) that feeds on leaves from riparian shrubs and trees. Photo: Aquatic Ecology, University of Duisburg-Essen

Based on the reviewed literature, the study found that woody riparian vegetation had consistent effects on the supply of leaf-litter and large wood to rivers. Leaves are a fundamental food source for riverine insects in upland rivers, where primary production is strongly limited, and where the food web of aquatic organisms relies on the input of terrestrial carbon.

Woody debris – such as fallen trees, tree trunks, branches and twigs – often increases habitat quality and variety in rivers. Besides the input of organic material, bankside vegetation also provides shade and can effectively ‘dampen’ water warming in spring and summer.

However, despite the observed positive effects of riparian vegetation, this review article also revealed weak and inconsistent effects on the biological quality and diversity of river organisms after riparian restoration. Unfortunately, the reasons behind this finding remained unclear, given that just a small fraction of the reviewed studies included biological effects at all.

Large woody debris in the restored Lippe River in Germany. Image: Benjamin Kupilas | REFORM

Leader of the study, Dr. Christian Feld said, “Land management such as farming or forestry are essential for society – but can damage rivers downstream. We therefore need ways to reduce their unwanted effects, and management of the riparian zone has long been proposed as a cost-effective and local solution. Our evidence shows that riparian restoration can be effective in offsetting some problems, but not all. Larger-scale problems such as pollution from agricultural chemicals or sediments will need larger-scale solutions applied through improvements in the management of whole river catchments.”

Feld highlights the unclear effects of riparian restorations in the retention of nutrients and sediments originating from farmland on the floodplain. The study showed that only riparian plantations that combined trees, shrubs and grasses could effectively reduce nutrient and sediment pollution. However, even then, riparian restorations had only a limited effect where the catchment further upstream was intensively used by agriculture. In contrast, positive effects were more pronounced if riparian restorations took place in the upper parts of the catchment, where the aquatic environment is stronger linked to the riparian conditions.

Professor Steve Ormerod – Co-Director of Cardiff University’s Water Research Institute and co-author of the study – added, “This whole issue is one that needs more holistic ecosystem management. Fresh water is a crucial human resource that needs care, maintenance and sometimes very expensive treatment before it can be supplied to people. Freshwater ecosystems are also losing biological diversity at an alarming rate globally because they are not well protected. We need to step up efforts to balance productive land use against these downstream costs – and our work shows that this needs a blend of local riparian solutions as well as improved large-scale thinking.”

Overview of a restored river section five years after restoration. This riparian zone can effectively buffer the river system from adverse land use impacts on the floodplain, while the shade and organic material provided by the vegetation can promote the instream biology. Photo: Viktoria Berger.

~

The work was funded by the EU MARS project under project No.: 603378

Does water management pay off? Introducing the DESSIN Ecosystem Services Approach framework

The Emscher River in Nordsternpark, a former mining site in Gelsenkirchen, Germany. Image: M. Knuth | Flickr Creative Commons

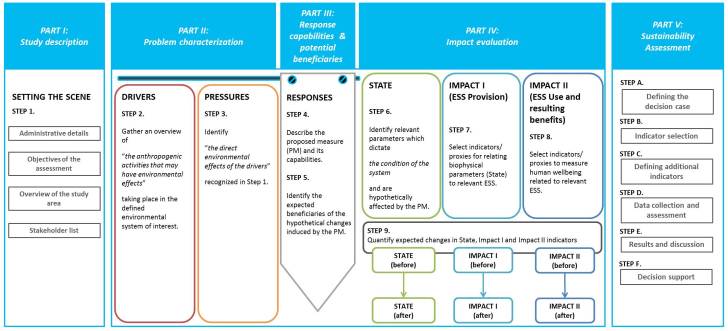

Two new studies on the potential of the ecosystem services approach in strengthening European water management have been published in the Ecosystem Services journal. Both studies were supported by the EU-funded DESSIN project.

The first study provides a practical guide for water managers to assess changes in ecosystem services as a result of different water management measures. Lead author Gerardo Anzaldúa and colleagues outline that innovative solutions to water quality and quantity problems – such as groundwater replenishment and combined sewage treatments – are continually advancing and improving. However, they argue that existing impact assessment methodologies for investigating their impacts are increasingly limited. An ecosystem services approach can help both the assessment and communication of the impacts and benefits of new water management approaches on human lives, the authors argue.

Anzaldúa and colleagues found that whilst there are already ecosystem services (or ESS) assessment frameworks available to help environmental decision-makers and managers, many existing approaches do not adequately link ecosystem changes to ecosystem service provision. In addition, these assessment frameworks are often data intensive, focus on single issues (such as water scarcity) or service types (such as provisioning services), and – importantly – don’t easily link to Water Framework Directive assessments (although, see the 2015 MARS ‘cookbook’ approach to assessment and valuation)

The DESSIN Ecosystem Service Evaluation Framework – structured guidance for ecosystem service assessment. Image: Anzaldua et al. (2018)

The new DESSIN Ecosystem Services Approach framework outlined in their paper aims to address these gaps and shortfalls. The framework is designed to allow users to evaluate and account for the ecosystem service impacts of new and innovative water management approaches. It is intended to complement the implementation of Water Framework Directive River Basin Management, and incorporates a similar DPSIR approach to adaptive management.

The framework is designed to support local-scale evaluations of ecosystem service provision, which are intended to help make assessments more accessible and useful for both stakeholders and decision-makers, and can be scaled-up to river basin and national scales. You can read the full details of the framework in the open-access study here.

An unrestored (left) and a restored section (right) in Dortmund Aplerbeck in the Emscher catchment. Image: Emschergenossenschaft.

The second paper provides a case study of the DESSIN Ecosystem Services Approach framework in use relating the to the restoration of the Emscher River in Germany. Restoration management to improve the ecological health and status has intensified on the Emscher in recent years, in an effort to reverse decades of water pollution, habitat loss and riverbank alteration.

To assess the values of restoration efforts, Nadine Gerner and colleagues applied the new DESSIN framework to evaluate the provision of regulating (self-purification of water, nursery populations and habitats and natural flood protection) and cultural ecosystem services (aesthetic, recreational and educational values) along stretches of the Emscher.

The research team used economic assessment methods including damage costs avoided, contingent valuation and benefit transfer. They estimated that restoration efforts on the Emscher generated a direct economic impact or market value of over €21 million per year. Market value here means the direct economic benefits to local communities and businesses, such as increased house prices or recreational opportunities.

In addition, they calculated that the non-market value of restoration exceeded €109 million per year. Non-market values includes both willingness to pay and avoided cost calculations and include benefits such as reductions in flooding risk . You can read the full step-by-step application of the DESSIN framework to the Emscher case-study, and the methods and justifications of value calculation in the open-access study here.

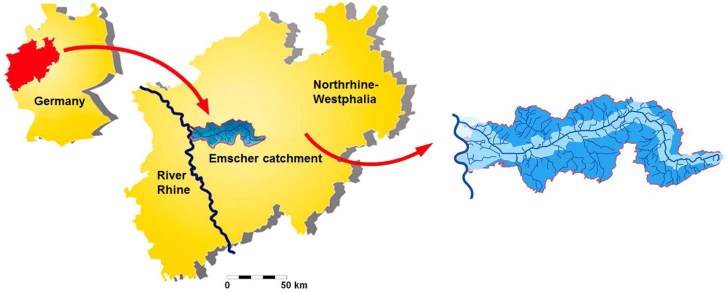

Map of the Emscher catchment in Germany. Image: DESSIN

Gerardo Anzaldúa from the Ecologic Institute in Berlin says, “The attractiveness of the Ecosystem Services Approach resides in its potential to enable individuals with diverse backgrounds and interests to communicate in terms of the inherent value they see in nature. This does not refer only to the monetary worth of ecosystems and their outputs, but to the variety of benefits that humans in direct or indirect contact with them perceive. Unfortunately, this wide-ranging character of the approach is at the same time what has made it so elusive to put into practice, as different disciplines have their own set of rules to understand and solve problems.”

“In DESSIN we had the chance to bring together a core group of ecologists, economists, engineers and sociologists under a single common goal: developing a way to run locally relevant and practicable ESS evaluations,” Anzaldúa explains.

Before (left) and after (right) construction of Lake Phoenix and restoration of the Emscher in Dortmund. Image: City of Dortmund / Emschergenossenschaft.

Nadine Gerner from Emschergenossenschaft continues, “In this way, the DESSIN ESS Evaluation Framework was developed on the basis of three case studies where restoration projects and innovative solutions had already been implemented in the past. Therefore, it was possible to compare the status before and after the solutions were implemented. The case studies were distributed throughout Europe in order to cover a broad geographical range with diverse environmental conditions and social dimensions as well as a wide variety of ESS types.”

“Ongoing restoration measures as part of the reconversion of the Emscher River in Germany were evaluated with regard to their impact on ESS provision, use and benefit. Regulation and Maintenance ESS – such as the self-purification capacity, maintaining nursery populations and habitats and flood protection – were evaluated, as well as Cultural ESS describing aesthetic, recreational, educational and existence values.” Gerner says.

An art installation by Tobias Rehberger at Emscherkunst, an exhibition of contemporary environmental art along the banks of the Emscher. The river basin is increasingly a space for recreation and tourism. Image: Reinhard H | Flickr Creative Commons

Read the new open-access papers in full here:

A new atlas of European caddisflies

Chaetopteryx rugulosa has a small distribution area in the Eastern Alps, and is split into several subspecies. Image: © Graf & Schmidt-Kloiber

A major new European atlas of the distribution of caddisfly species (or Trichoptera) has recently been published, providing the first comprehensive overview of their occurrence patterns across the continent. Based on data collected over 7 years from over 630,000 species occurrence records, the Distribution Atlas of European Trichoptera features 1,579 maps of a fascinating, diverse and ecologically-important insect order.

Whilst freshwater ecosystems are known to support a rich diversity of species – there are more than 14,500 caddisfly species, of which more than 1,700 occur in Europe – their distribution maps are often patchy and incomplete. Comprehensive species mapping – as carried out here by the Atlas team – is important in guiding future scientific research and environmental policy and management.

Atlas co-author Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber says, “The Atlas shows us the distribution ranges of every single caddisfly species in Europe, it reveals common species as well as rare ones and identifies Trichoptera hot spots. With the help of fellow caddisfly experts we compiled occurrence records from all over Europe into one single database, which now serves as a valuable base to establish a European IUCN Red List of threatened species.”

Limnephilus subcentralis – as many other Limnephilidae species – covers a huge range from Scandinavia to the Balkans and from Belarus to UK. Image: © Graf & Schmidt-Kloiber

The idea for the Atlas was first discussed in 2005 at the ‘First Conference on Faunistics and Zoogeography of European Trichoptera’ in Luxembourg. The Atlas project was kick-started in 2011 as part of the EU-funded BioFresh project, and includes data contributions from 83 Trichoptera experts (see this open-access Hydrobiologica article for more detail).

Co-author Wolfram Graf explains, “The Atlas is a milestone in Trichoptera research: up to now species distribution ranges were only indicated on country level – such as Fauna Europaea – or on an ecoregional level – such as through the freshwaterecology.info portal. For the Atlas we collected point records. This, for the first time, reveals the real distribution range of a species. The Atlas serves to delimitate diversity spots and refuge areas for endemic species on different scales and is therefore an essential basis for any conservation issue.”

The Atlas shows that areas of southern Europe – particularly in Spain, Italy and the Balkans – and mountainous regions (such as the Alps and the Carpathians) support both high caddisfly biodiversity and endemism. In other words, these areas harbour a high biodiversity and support certain rare species which are not found anywhere else.

Species of the family Limnephilidae are found all over Europe, but several genera have very limited distributions. Image: Distribution Atlas of European Trichoptera

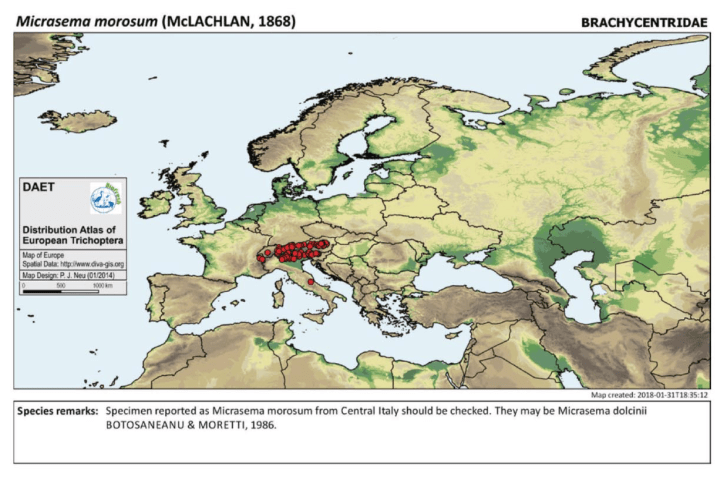

Micrasema morosum is a caddisfly species predominantly found in the Alps. Image: Distribution Atlas of European Trichoptera

In general, overall caddisfly species diversity decreases with increasing latitude. There is a similar drop in species diversity in the move from Western Europe to Eastern Europe, largely because caddisfly-rich mountainous areas are lacking on the eastern plains of the continent. In several cases, distinctive Atlantic and Siberian species – which underwent speciation processes in glacial ‘refugia’ in the last ice age – overlap in areas of Central Europe. These climate-induced speciation processes in ice-free parts of the content account for the increased present-day species diversity in Southern Europe.

Areas rich in caddisfly biodiversity and endemism such as the Mediterranean are particularly threatened by the ongoing effects of climate change and other anthropogenic pressures. The Atlas identifies these areas of conservation importance, which can subsequently help raise their visibility as an issue amongst environmental policy makers in Europe.

Leptocerus interruptus is a delicate species with a wide distribution throughout Europe. Image: © Graf & Schmidt-Kloiber

Co-author Peter Neu outlines the value of the Atlas, “By delineating the distribution areas, the Atlas provides invaluable help in identifying species that are difficult to distinguish and therefore also serves as a quality control tool for all future identifications, for example, for people who identify specimens from regions whose fauna is not familiar to them, the Atlas is a great decision aid. Through the Atlas, we can further identify species for which there is still a research need.”

Wolfram Graf continues, “The Atlas enhances our knowledge on evolutionary theories as well as on zoo- and phylogeographic aspects. The depicted maps are just the beautiful surface but the basic data are the true treasure which will be analysed in-depth now. The Atlas may be an inspiration for us and others to continuously collect faunistic data in order to be able to analyse long-term developments of this fascinating insect order in a changing world.”

Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber concludes, “As the success of the Atlas very much relied on the willingness of our colleagues to contribute data, I want to take the opportunity to thank them once again for their enthusiasm and great work!”

The Distribution Atlas of European Trichoptera is published by Conch Books

Image: Jim Liestman | Flickr Creative Commons

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is the foundation of European Union water policy. Adopted in 2000, the WFD provides a policy framework for European member states to monitor, assess and manage their aquatic ecosystems. However, despite widespread improvements in the monitoring, conservation and restoration of rivers and lakes across Europe, the WFD has not yet achieved its primary objective: the good ecological status of all European freshwaters.

Part of the rationale for the MARS project’s work over the last four years has been to assess the success of the WFD in addressing contemporary issues for European water management. When the WFD was designed and developed in the 1990s, the issues facing Europe’s rivers and lakes were somewhat different to today. Strong single stressors such as nutrient pollution and water abstraction were common across the continent. In the time since, the challenge of multiple stressors – where stressors act in tandem, causing complex interactions and ecological impacts – has emerged.

Similarly, new challenges such as the pollution of microplastics and synthetic chemicals into water bodies means that water managers need to stay alert to the possible impacts of emerging stressors. However, new water body monitoring techniques for both ecological health and stress – such as those used for dissolved chemical ‘cocktails’ in the SOLUTIONS project – are being developed, providing new opportunities for effective water management.

Microplastics. Image: Florida Sea Grant | Flickr Creative Commons

A formal EU ‘fitness check’ evaluation of the WFD in the context of these developments is due in Autumn 2019. Ahead of this assessment, MARS researchers have published a policy brief providing recommendations for the future implementation and evaluation of European water policy. They identify four key areas to be addressed:

Monitoring and assessment systems

The researchers argue that whilst the WFD has significantly advanced the environmental monitoring and assessment of European water bodies, there are a number of problems with the current approach. They suggest that the strategic design of monitoring networks can be improved across the continent, and that monitoring the ecological effects of restoration management can be enhanced, for example, by using ‘early responding indicator’ species and metrics.

They highlight the concern that the WFD assessment uses overly strict criteria to define success, in which the overall ecological status of a water body is determined by the lowest of its biological, physical and chemical quality elements – potentially obscuring a more nuanced picture of the ecosystem. Finally, they outline the value of incorporating new monitoring tools such as earth observation, genomics, automated monitoring platforms and citizen science into WFD assessment, where appropriate.

Management measures

River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) are a key WFD management tool. They are based on ecosystem monitoring data and outline management plans for entire river basins, addressing not only water bodies but also the drivers of environmental stress such as agriculture, hydropower and flood protection. In their policy brief, MARS researchers suggest that RBMPs can be improved through more targeted planning and implementation of measures to manage the emerging impacts from multiple stressors across Europe.

They highlight the availability of data and diagnostic tools to identify stressors and their interactions (such as those developed by MARS), which can help design effective and cost-effective management measures. They outline the value of trait-based diagnostic tools which can help diagnose the mechanisms behind environmental degradation; and of ecosystem service indicators which can provide powerful messages to the public and policy makers about the benefits of freshwater conservation and restoration.

Agricultural terraces in the Douro River Basin, Portugal. Image: Malcolm Payne | Flickr Creative Commons

Policy integration

The MARS researchers argue that there is a need to harmonise and integrate the objectives and management of the WFD with other key European policy frameworks. One key policy relationship is with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Diffuse pollution and habitat degradation as a result of agricultural activity are common pressures across the continent, and there is a need to make farming increasingly ‘water friendly’. A key aspect of this is in regulating pollution events, in terms of who should bear the cost of measures to restore ecological status and flood protection, when the source and impact of pollution events can be geographical dispersed.

The authors highlight the need to better account for climate change in the WFD, stating that drought and water scarcity are poorly addressed in the WFD. They suggest that the Floods Directive could be brought into the WFD, and synergies over natural flood protection measures could be emphasised. Finally, the MARS researchers suggest that bringing an ecosystem services approach into the WFD could help integrate land and water policy goals, and make explicit the costs and benefits of conserving and restoring natural capital.

Beyond 2027

A key message of the new policy brief is that whilst the WFD is the ‘most important step even taken towards sustainable water management in Europe’, there is the pressing need to make sure it is ‘future proof’ and can address new and emerging water management issues.

The third and final WFD River Basin Management Cycle ends in 2027. The authors suggest that it is unlikely that Europe’s water bodies will have reached good ecological status – a key aim of the WFD – by this date. This is largely because the ecological effects of ecosystem restoration can take many years to occur.

The authors argue that there is thus a pressing need to decide on the future of the River Basin Management mechanism beyond 2027. In short, there needs to be a framework in place to encourage European member states to continue to monitor, conserve and restore their rivers and lakes after 2027. They conclude that, ‘An extension of the River Basin Management mechanism, keeping the ambitious targets, and restricting the option to apply further time exemptions, is now required to make the WFD future proof.’

+++

World Fish Migration Day – 21st April 2018

Events will be held across the world tomorrow to highlight the importance of free-flowing rivers and migratory fish. Hundreds of events are planned as part of World Fish Migration Day, involving groups of people and organisations on a diverse range of river and streams.

Migratory fish populations are threatened in many global rivers and streams. Often this is the result of multiple pressures such as barriers to migration (like weirs and dams), water flow alterations (such as agricultural abstraction) or damage to habitat (such as removal of spawning beds).

Migratory fish lifecycles can occur over very large geographic areas – with breeding, feeding and reproduction all potentially taking place hundreds of miles apart. This means that conservation and restoration actions often need to be coordinated over large areas. For example, for the Atlantic salmon in northern Europe, this includes managing fishing both at sea and in estuaries, alongside mitigating water pollution, conserving spawning grounds, and providing fish passes on weirs and dams.

Migratory fish often provide valuable sources of food and livelihood for local communities. They can also be important parts of large-scale nutrient cycles. For example, migratory Pacific salmon in North America and Canada carry nutrients upriver from the ocean, where they both provide food for predators such as bears, and also fertiliser for riparian ecosystems when their die and their bodies decay.

Pacific salmon migrating upstream. Image: World Fish Migration Day

The main goal of World Fish Migration Day is to improve public understanding of the importance of migratory fish, and to highlight the need for healthy rivers and the communities that depend on them. The events – co-ordinated by the World Fish Migration Foundation – aim to engage citizens around the world to take action on these topics. Through showcasing a global community of people and organisations passionate about conserving and restoring migratory fish populations, the World Fish Migration Day aims to agree lasting commitments from NGOs, governments and industry on safeguarding free-flowing rivers.

Clemens Strehl of the IWW Water Centre in Germany outlines the value of World Fish Migration Day, “I believe it is a great opportunity to raise awareness of this issue. Healthy rivers and fish migration mean increased biodiversity. However, it is a continual challenge to balance the need for rivers to provide services and benefits to humans – energy production and industry, hydropower, drinking water, agriculture, recreation, and so on – whilst at the same time achieving good ecological status. But fishes do not ‘scream’ in this struggle, so the World Fish Migration Day event is a nice opportunity to give them a symbolic voice.”

“There are many great opportunities to restore streams and waterways to encourage fish migration. See the examples from our area – Essen in Germany – where the Emschergenossenschaft took the challenge to restore a stream which had been degraded completely to an open wastewater channel. This former ‘sewer’ is now returning piece by piece to a healthy urban ecosystem. See our European water research DESSIN project and the latest open-access publication from Nadine Gerner and colleagues, which shows the many benefits of river restoration on the Emscher,” Strehl says.

The restored Lippe River in Germany. Image: Benjamin Kupilas | REFORM

“On the River Lippe in Germany, the sighting of one migratory salmon in a previously degraded river triggered enthusiastic reactions in the local area (see here and here for coverage). The Lippe was nominated as ‘River of the year 2018/19’ in Germany, as a result of successful restoration actions. On the Lippe – which crosses a former coal mining and industrial area, much like the Emscher – measures were taken to connect former non-connected stream sections and reactivate floodplain areas. This enabled a local fish species called ‘Quappe’ (Lota lota) to return to the Lippe system. Fishes do not ‘scream’, but they can be ‘happy’ – appropriately the symbol of the World Fish Migration Day is a happy fish!” Strehl says.

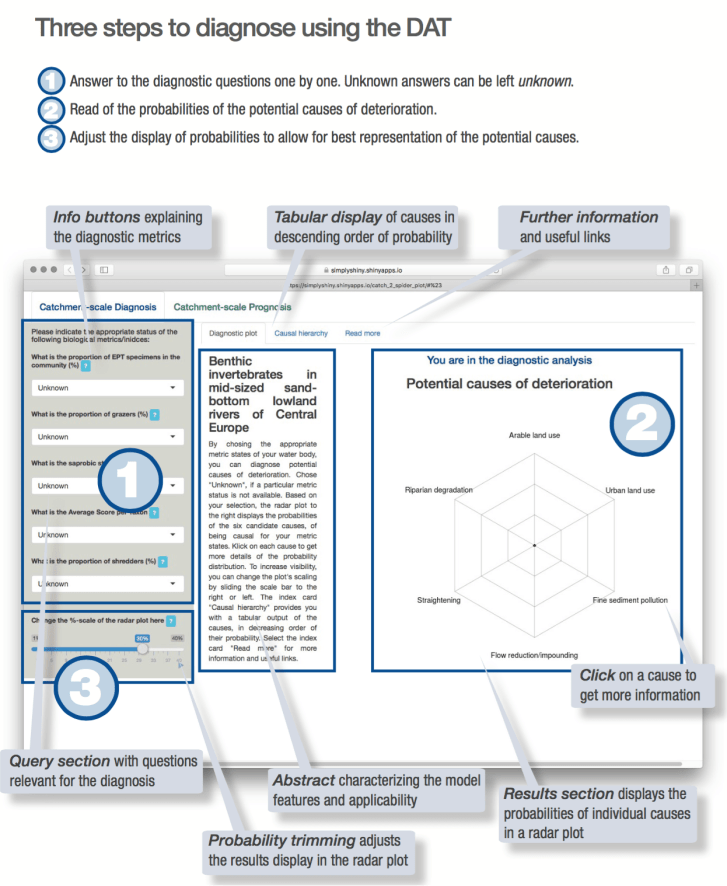

The MARS Diagnostic Analysis Tool visualises probable multiple stressor occurrence based on ecological data from a water body.

Rivers and lakes across Europe are subject to multiple human stressors, which can interact to impact freshwater ecosystem health and status. As a result, a key problem for environmental managers seeking to conserve and restore water bodies is identifying the multiple causes of ecological stress and degradation.

Modern ecological assessments are increasingly sophisticated and informative, but they generally do not give a picture of the causes of multiple human stressors acting on an ecosystem. This is because such assessments are generally ‘integrative’ and do not focus on individual stressors.

Over the last four years, the EU MARS project has developed a Diagnostic Analysis Tool (DAT) to help water body managers and policy makers to identify and rank potential causes of ecological degradation at the catchment, reach and water-body scale.

The DAT is freely accessible through the online Freshwater Information Platform. Users can enter values or ranges of biological metrics which indicate ecological status in a water body. Metrics that can be inputted into the DAT include community-based indices (e.g., percentage of EPT macroinvertebrate taxa), assessment indices (e.g., saprobic index) and ecological traits (e.g., feeding types).

The DAT uses a Bayesian network to calculate the probability of different causes of ecological degradation being present in a water body. This probability can be visualised through graphs and tables. In effect, the DAT works like a doctor’s ‘health check’ for water bodies, in which the causes of illness are diagnosed based on a patient’s symptoms.

The DAT ‘diagnoses’ the probable causes of ecological degradation, based on their inputted ecological ‘symptoms’. Possible drivers of multiple stressors – arable and urban land use, riparian degradation, channel straightening, flow regulation, fine sediment pollution, habitat loss – are ranked in order of probability.

Descriptions of each driver, and possible mitigation approaches, are then provided through the tool’s interactive interface. This provides potentially valuable information for water managers seeking to minimise biodiversity losses and ecosystem alterations in their water bodies.

The DAT has been developed based on MARS research and modelling for mid-sized sand-bottom lowland rivers of Central Europe. However, it can be tailored by interested users to work for other water body types. Full documentation on how to modify the DAT can be found here (pdf) and guidance can be given by MARS scientist Christian Feld by email.